A Short History of SF

Rich Paul Cooper

Introduction

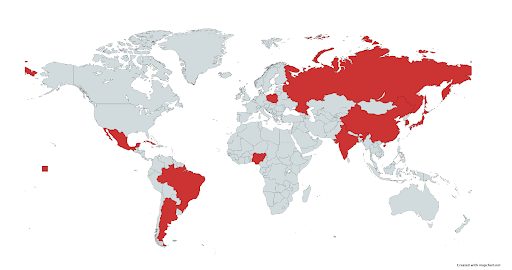

In this section, we explore the history of SF through different national traditions, aesthetic movements, subgenres, and mediums.[1] Traditional mediums through which audiences would have consumed SF include literature, comic books, and TV/film, but many newer audiences discover science fiction through the medium of video games. In terms of genre, many critics find it easy to pigeonhole science fiction as action-driven hyper-masculine space adventures, and certainly that description encompasses much military SF and space opera, two subgenres of SF. However, beneath the larger generic umbrella of SF, there are many subgenres, sub-types of stories within the larger genre that could never be described as hyper-masculine space adventures. Many of those subgenres will be enumerated at the end of this chapter, but with the perpetual advent of new genres and reading communities, such a list could only ever be incomplete. Though much science fiction is, in fact, wish-fulfillment written by men from advanced industrial nations (America, Britain, and France), we will see below how other identities—races, sexualities, nationalities, and so forth—impact the collective future imagination of SF. [2] By the end of this section, the massive scope of SF will be apparent. SF is, simply put, a world literature.

No account of SF could ever be complete. SF is a large field of literature dominated historically by publishing houses that produced a great quantity of varying quality, from grocery store mass paperbacks to international bestsellers. Since Hugo Gernsback’s stewardship over Amazing Stories, the first SF magazine, publishers such as Ballantine, Ace, and Del Rey, among others, continue to play a vital role in connecting writers to audiences. This narrative will also be incomplete because as science progresses, so does science fiction. Whatever direction the future of SF takes (let us hope it takes some unexpected turns), one thing is certain: In the case of SF, more and more, the gap between fiction and reality is closing. With every advancement in genetics, cybernetics, robotics and computing, our reality approaches the predictions of SF, making them manifest and inviting wider and weirder visions of the future. For example, in 2022 a Google engineer claimed that a chatbot AI (artificial intelligence) has become sentient,[3] a longstanding trope of science fiction. The point bears repeating: We live in a science fiction world. For this reason alone we should study SF, because few other genres have the ability to teach us so much about ourselves and modernity. As long as cities, computers, and advanced technologies constitute our reality, SF will continue to inspire critical thought and readerly pleasure.

The Gothic to the Golden Age

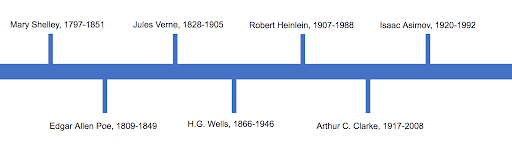

The timeline below highlights the major figures in the traditional canon of science fiction from its inception until the Golden Age of SF. Any student of science fiction knows that science fiction predates Mary Shelley. We could cite Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing Moon (1666) or Lucian of Somsata’s 2nd-century text Trips to the Moon, A True History. The traditional canon classifies these works as works of proto-science fiction, the ‘proto-’ designating pre-Enlightenment works of science fiction, a judgment that ultimately rests not upon literary parameters but epistemological ones. This traditional canon is also overwhelmingly Euro-centric, placing France, England, and the U.S. at the center of SF production. In fact, as shown below, a separate tradition of science fiction developed in Latin America during the 19th century, a tradition that deserves to be studied as seriously as Wells, Verne, or Shelley.

Figure 2.1 Timeline of major authors (and one editor) from Mary Shelley to the Golden Age

Figure 2.1 Timeline of major authors (and one editor) from Mary Shelley to the Golden Age

Mary Shelley is the “mother” of SF. That’s what critics call her; we’re not just making that up. Her 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus introduces what has served to be one of the continuing themes of science fiction, one especially pertinent to the advanced technological age we live in: the creation of new life and the duty of the creator to their creation. Since it seems that humanity finds itself on the verge of the technological singularity, the moment artificial intelligence exceeds human intelligence, and since we possess technologies such as CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) that allow us to transform genetic material, it should be no surprise that Frankenstein continues to resonate with us over two centuries after its initial publication.

Well, if Shelley’s the mother, who’s the father?

Someone with a little pop culture knowledge about SF might mention one of the “Big 3”: Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, or Robert Heinlein. Who couldn’t forgive them for their error? Who hasn’t seen Alex Proyas’ I, Robot (2004), Paul Veorhoeven’s Starship Troopers (1997), or Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)? The first two are films based on Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (1950) and Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (1959). The final is unique because while Kubrick used Arthur C. Clarke’s ideas for base material, the novel (1968) was released after the film. These three writers occupy a major place in the collective imagination of SF, but none of them is the father of the genre. If anything, they were benevolent uncles guiding the genre through its teenage years.

Jules Verne and H.G. Wells both have better claims to the title “Father of SF.” Even if you do not recognize their names, you have surely seen a film or television show adapted from their stories. H.G. Wells is famous for The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), and The War of the Worlds (1897), while Jules Verne is best known for works such as Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1872), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873). Despite the fact these writers are among the first writers of SF, perhaps it is better to speak of changing cultural and material conditions rather than the genius of any specific author as “progenitor.” The world was undergoing radical changes to the economic and social order, changes that were the necessary and sufficient conditions for the proliferation of the SF imagination.

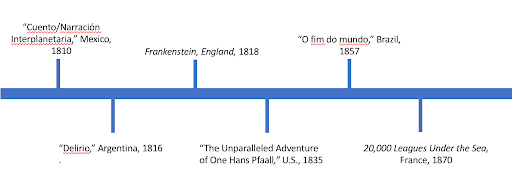

If there is one single person we could point to as the “father” of SF, it would have to be Edgar Allen Poe. Many do not think of him as a science fiction writer, but he is cited by Wells, Gernsback, and others as a direct influence. His 1835 short story “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” certainly counts as science fiction, since the protagonist travels to the moon. To recall the discussion from the introductory chapter, Poe’s case highlights the high/low culture divide at work within science fiction. Some science fiction writers come to be celebrated as part of the literary canon not because of their science fiction but despite it, revealing the continued bias some scholars and readers have toward the marvelous genres, a bias rooted in Enlightenment-era assumptions about fictions that stray too widely from empirical reality.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning the “godfathers” of SF, editors whose stewardship connected writers to readers and served to popularize the genre. Joseph Campbell spearheaded Astounding Science Fiction, one of the first and most influential pulp fictions, but it is Hugo Gernsback who holds the title of first in this arena. In 1926 he published the first issues of Amazing Stories, bringing the works of writers like Wells to a popular audience. Because of these editors, SF erupted in the mid-20th century, a boom we call the Golden Age of SF.

The Gothic to the Golden Age: Questions and Activities

- When was the Golden Age of science fiction? What societal conflicts defined this period?

- Who are the “Big 3”? Have you seen any films based on their novels?

- Who are the “godfathers” of science fiction? What magazines did they start?

- In what year was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein published? How many editions were released? What are the differences between those editions?

- What is the technological singularity? Can you find stories about AI becoming aware in the news?

Wish Fulfillment to World Literature

Though SF matured during the Golden Age, it was still rooted deeply in action, adventure, and romance. SF is, foremost, a popular genre. Taking this popular quality in mind, many critics charge that science fiction is a literature of escapism. Following the logic of those same critics, science fiction does not induce critical thought about reality because it facilitates escape. Less gracious critics might even charge that science fiction is a literature of juvenile wish fulfillment, particularly the juvenile wishes of cishet white men from modern industrialized colonizer states. The editors of this volume are in disagreement. While these characteristics certainly define much science fiction from the 19th and 20th Centuries, by the end of this section you will have gained a sense of how different identities, national or otherwise, have shaped the SF imagination. This process has led to SF becoming a world literature in the 21st Century.

Let’s start with the multiple identities within pluralistic and diverse societies such as the United States. SF is associated with the juvenile wish fulfillments of cishet white men because that was the primary demographic to which early science fiction was marketed, yes, but also because much of the early fiction took a certain form that could be described as follows: A young man, perhaps physically inept but intellectually capable, happens upon a spaceship, and, armed with only his wits, he saves the universe from certain destruction, and, in the end, rescuing the “damsel in distress.” Often, saving the universe involves subjugating some lesser species through greater technological superiority, and, rather unfortunately, racist themes of subhuman erasure are prominent. Take for example James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), where the native species is subjugated in a way that effortlessly correlates to the subjugation of Native Americans by the early settler-colonizers.

Some credit here should be given to the “Big 3” writers of the Golden Age. In their hands science fiction was elevated to a metaphysical literature of ideas. Despite this, SF still needed to shake up the old forms in order to create the conditions where different identities could explore and enjoy SF visions of the future. Starting in the 1960s, the New Wave challenged the old guard of the Golden Age with new voices and experimental forms. Once again, editors played a vital role, particularly Michael Moorcock, who took over as editor of New Worlds in 1964. The New Wave experimented with new forms, drawing for example from surrealism, opened the genre to a more diverse authorship, and emphasized soft SF as opposed to hard SF. Championing the scientific study of people and cultures, soft SF contains an implicit orientation toward difference and diversity as a matter of scientific rigor. It should come as no surprise, then, that the New Wave gave voice to women writers such as Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin, and James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon), and to queer writers such as Thomas Disch and Samuel Delany. By opening SF to new perspectives, the New Wave made possible movements such as afrofuturism, a term used to describe the contributions of African-American SF writers. Luminaries of afrofuturism include W. E. B. DuBois, Samuel Delany, Octavia Butler, and N. K. Jemisin. The New Wave also paved the way for feminist futurisms and queer futurisms.

A Few Queer Futurisms

- Joanna Russ, The Female Man, 1975

- Samuel Delany, Stars in my Pockets like Grains of Sand, 1984

- Becky Chambers, The Wayfarer series, 2014-2021

- N. K. Jemisin, The Broken Earth Trilogy, 2015-2017

- Janelle Monae, The Memory Librarian: And Other Stories of Dirty Computer, 2022

Looking outward beyond national borders, SF exhibits even more diversity and vigor. During the early to mid-20th century, the USSR produced a vast amount of SF, much of it still unknown in the anglosphere. Perhaps one of the most famous SF authors from the former USSR was Poland’s Stanislaw Lem, whose masterpiece Solaris (1961) has been adapted to film at least twice, the first time in the 1970s by the Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, the second time in the 2000s by Steven Soderbergh. In Russian SF from this period, there is much optimism and hope. For example, the brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky often wrote about agents from earth who travel to less advanced situations to render aid and help them progress. Much of Russian SF could be called part of the utopian tradition, and, indeed, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We (1924) is part of our chapter on that tradition. Many Russian SF writers even found the genre to be useful for thinking about questions that might be forbidden by state censorship.

In Latin America, the SF tradition is often mislabeled as “magic realism” so as to feed expectations of exoticism in anglophone audiences. Yet when the SF traditions of Latin America are considered in full, the timeline of development demonstrates an SF tradition that rivals those of Europe and the U.S. In Argentina, Antonion José Valdés’ short story “Delirio” was published in 1816; in Brazil, Joaquim Manuel de Macedo’s short story “O fim do mundo” was published in 1857; and in Mexico, an anonymous story called “Cuento,” or, “Narración interplanetaria” was published in 1810.[4]

Though many great works are unavailable to those who do not speak Spanish or Portuguese, many other works have been translated into English, such as Argentinian writer Angélica Gorodischer’s Trafalgar, published in 1979 but translated in 2013, or Cuban writer Yoss’s Red Dust, published in 2004 but translated in 2020. As you can see from the examples from Latin America and East Asia, there is often a lag, due to the time of translation, between when a text appears in its original language and when it appears in English. As we more and more come to consider SF a world literature, this lag will close, and the SF imagination will be formed more immediately by visions from all around the world.

For many English speakers, to read works from non-English traditions requires the dedicated work of translators, but English is a world language, and there are alternative traditions of SF in English on every continent, especially in the places formerly colonized by English-speakers. In India, authors write postcolonial SF. What makes for postcolonial science? Isn’t science just science? Consider Amitav Gosh’s The Calcutta Chromosome (1995) as an example. Staged as a taut thriller that moves across time and space, The Calcutta Chromosome retells the discovery of the mechanism by which malaria was transmitted. In the colonialist books, Sir Ronald Ross is credited; in The Calcutta Chromosome, he is given this knowledge by an ancient mystical movement seeking to unlock the secrets of immortality. For some time, this secret group had been using the malaria virus to bypass the blood-brain barrier, their understanding of malaria far exceeding the understanding of British science. In this way, the traditional practices and knowledge of the Indian people create scientific advances which undermine the narrative that science requires a Western, Enlightenment worldview.

This postcolonial attitude also persists in Africa, where Nigerian writers especially have offered invaluable contributions to the SF imagination. Temi Oh’s Do You Dream of Terra-Two? (2019), Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti_Trilogy (2015–2018), and Tade Thompson’s Rosewater series (2016–2019) stand out in this saturated field. From Buenos Aires to Hong Kong, from Calcutta to Lagos, science fiction has cemented its status. If science fiction is in part about future visions of alterity, then that vision can only grow with the inclusion of as many voices as possible. Take for example Okorafor’s Lagoon (2014). The text portrays an alien invasion in Lagos, one that is stopped by a marine biologist, a disgraced soldier, and a famous rapper. Much like the city of Lagos itself, it is through hybridization that they come to “halt” the invasion. They do not destroy the outsiders, rather they find a way to live in common. Since Lagos is an international city of hundreds of languages and dozens of ethnic groups, hybridity is an essential survival technique.

There are also rich SF traditions throughout the sinosphere. Japanese manga are a source of much science fiction, as are many Nintendo video games, which were released in Japan before they were released in the U.S. In addition, South Korean films have seen a boom in the past two decades, and many of those films are great works of science fiction. Bong Joon Ho’s films Okja (2017) and Snowpiercer (2013)[5] are celebrated works, as is Yeon Sang-ho’s zombie film Train to Busan (2016). Thanks to the work of Ken Liu, an American born writer and translator, Cixin Liu’s Three Body Problem (2007) became available to the English-speaking world and went on to win the 2015 Hugo Award nearly ten years after its first publication in Chinese. Ken Liu also translated Qiufan Chen’s The Waste Tide (2013) into English in 2019, six years after it was first published.

Wish Fulfillment to World Literature: Question and Activities

- When we call SF a literature of wish-fulfillment, to whose wishes does this usually refer?

- When was the first science fiction story published in Mexico?

- Explain in your own words the difference between soft SF and hard SF. Which do you prefer? Why?

- What makes postcolonial science fiction unique?

- What country in Africa has produced a great deal of contemporary English-language science fiction?

Comics, Films, and Video Games

All three of these mediums share a special relationship with science fiction, and that’s not hyperbole. “Medium” refers to the method of distribution and consumption. Literature is a print medium. But comics, TV/films, and video games are all visual media. Comics and video games incorporate elements of print mediums, but their primary mode of delivery remains visual. Films are predominantly visual. In every case, the earliest examples of each of these mediums are works of science fiction. For a deeper understanding of these different mediums, see either this text’s companion volume Surface and Subtext or this text’s subsequent chapters which focus on specific mediums.

Some of the earliest works of science fiction were printed as pulp fictions, fictions named after the cheap paper on which they were printed. Amazing Stories, the first SF serial magazine, was printed on such pulp paper. The first comics were also printed on similar puklp. When we say “comics” we mean sequential art such as comic books or graphic novels, mediums that employ images in sequential order. Unlike serialized comic books that might run in perpetuity, graphic novels usually have fixed endings, but the line is blurred by the fact that many comic books have been anthologized as “graphic novels.” Sequential art is also famous in the form of manga, a form of sequential art that originates in Japan and is traditionally read right to left.

A Few Comic Books, Graphic Novels, and Manga

- Philip Francis Nowlan, Buck Rogers, 1929, first appearance

- Alex Raymond, Flash Gordon, 1934, first appearance

- Katsuhiro Ōtomo, Akira, 1982-1990

- Masamune Shirow, Ghost in the Shell, 1989–1991

- Warren Ellis and Darrick Robertson, Transmetropolitan, 1997

- Alan Moore and David Lloyd, V for Vendetta, 1989

- Alan Moore and David Gibbons, Watchmen, 1986–1987

- Garth Enis and Darick Robertson, The Boys, 2006-2012

TV/film share a special relationship with SF. George Méliès and his brother pioneered narrative films, which led to the production by Méliès of Le voyage dans la lune in 1902. This film depicts a moon landing party’s departure, foray, and eventual return. Thus one of the first narrative films ever produced is an SF film, a fact that illustrates the versatility of the filmic arts to capture the SF imagination, a versatility fueled secondarily by practical effects and primarily by special effects. Some critics even argue that this special relationship between SF and film has a deleterious effect on SF film in comparison to SF literature[6]. SF literature offers glimpses of a liberatory future, other worlds that spark critical thought about current reality. In SF film, this effect is dimmed in direct proportion to the amount of money spent on special effects. As such, much of SF film has glorified war, death, and militarization in ways that support the status quo; for an obvious example of such crud, take a film like Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day (1996), which barely manages to rise above the level of jingoistic endorsement of the United States and its military force as a world-saving necessity. Or compare the Ridley Scott’s first Alien (1979) to James Cameron’s sequel Aliens (1986). The latter is an action-adventure bug-hunt, the former the story of a woman overcoming a deeply horrific hostile alien encounter only made worse by corporations and greed. In short, as production companies push for greater returns on their investments, the narrative formula becomes more and more predictable. So, what do you think—do budgetary concerns hinder the complexity of the message in SF films? To use a contemporary example, how would you rate the Marvel films by these standards?

Despite this correlation between production costs and message, many SF films are noteworthy for more than their historical status. Fritz Lang’s German expressionist film Metropolis (1927) offers futurescapes that hold up even under digital scrutiny, and the robot-led worker’s revolt offers genuine liberatory hope. During the 1950s, much of SF film was concerned with themes and ideas drawn from Cold War anxieties such as Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach (1959). Such Cold War tensions continue, but such SF became less popular as the U.S. was consumed by the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement. Important French SF films were released in the early 1960s, experimental films such as Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), which influenced Terry Gilliam’s time-traveling film 12 Monkeys (1995), and Jean Luc-Godard’s Alphaville (1965). The 1960s then culminated in an SF event, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a film that drew big crowds; leaving some thrilled, some angry, and a great many confused, the film set a standard for what was possible for SF film.

SF also emerged from the 1960s as a television phenomenon in the form of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek, which aired in 1966. Since the 1990s, with the airing of Star Trek: The Next Generation, there has been a television series based in the Star Trek universe on air almost consecutively through the present day. And of course SF is huge in animated television and films; I mean, even the freshest noob can name Rick and Morty (2013–present) or Futurama (1999–present). In animated film and TV, effects are rendered much cheaper by virtue of the fact of animation, a process that has become increasingly digital. In fact, digital filmmaking is the norm, and CGI (computer generated images) has transformed SF film, opening it up to even wider audiences. The two highest grossing films ever made are both works of SF created after the advent of CGI, on which both of them rely heavily; those films are James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) and the Russo brothers’ Avengers: Endgame (2019). As you can see, this special relationship between SF and film/TV has never wavered, though it is perhaps safe to say, quite confidently, that SF film/TV is now more popular than ever. If box-office sales are any indicator, they are the most popular films ever.

Another popular digital medium traffics heavily in SF. Whether played on consoles, at arcades, through PCs, or virtually, video games have had a profound impact on the SF imagination. It’s true a lot of SF video games are essentially military SF, the medium providing the user a way to engage in digital warfare. Space Invaders (1978) is the first fixed shooter game, and it was available on consoles such as the Atari 2600 but also in arcade format. Included in the military SF wing of SF video games would be side-scroller 2-dimensional shooters such as Contra (1987) and 3-dimensional first-person shooters such as Doom (1993) or the Halo series (2001–2021). But not all SF video games are shooters. Many rely on mood, worldbuilding, and storytelling in a way similar to that of the greatest SF literature. Some SF video games rely on a mood of terror, horror, and suspense, characteristics quite evident in the zombie-virus infected Resident Evil (1996), the monster-space-alien-pursuing first-person adventure Metroid Prime (2002), an installment in the Metroid series that deviated sharply from the side-scroller shooter action of Metroid (1986), and the horror-survival-puzzle adventure Dead Space (2008).

World-building and storytelling are central to role-playing games (RPGs) where SF is well represented. Players can explore vast worlds, such as in the post-apocalyptic retrovisions of the Fallout series (1997–2018) or the magic-technology infused realms of the Final Fantasy series (1987–2021), both representing two very different sorts of SF worlds. SF RPGs also tell stories. EarthBound (1994), for example, allows the player to take on the point of view of a small-town hero as he bands with his friends to fight off an alien invasion. Early SF RPG storytelling is best represented by Chrono Trigger (1995), a truly ground-breaking SF video game wherein the actions of the characters traveling through time affects the course of the plot, leading to a non-predetermined end. Choose-your-own-adventure stories were incongruent to the bound paper medium of the book, but the branching plots and possibilities of such storytelling find a comfortable home in video games.

Comics, Films, Video Games: Questions and Activities

- What was the first science fiction narrative film? Who directed it?

- What is the name for the Japanese style of comic books that includes much anime?

- What is unique about the relationship between science fiction and film?

- What is a side-scroller game? A first-person adventure?

- What is a role-playing game?

Attribution: Cooper, R. Paul. “A Short History of SF.” In Marvels and Wonders: Reading, Researching, and Writing about SF/F. 1st Edition. Edited by R. Paul Cooper, Claire Carly-Miles, Kalani Pattison, Jeremy Brett, Melissa McCoul, and James Francis, Jr. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2022. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- For an extended history of the genre, we recommend The Cambridge History of Science Fiction, edited by Gerry Canavan and Eri Carl Link, 2018. ↵

- For more discussion of marvelous literature and wish fulfillment, see Chapter 6: Roots of SF/F ↵

- Leonardo De Cosmo, “Google Engineer Claims AI Chatbot is Sentient: Why That Matters,” Scientific American, 2022. ↵

- Rachel Ferreira, The Emergence of Latin American Science Fiction, Wesleyan Press, 2011. ↵

- Based on the French graphic novel Le Transperceneige by Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette. ↵

- Carl Freedman, “Kubrick’s 2001 or the Possibility of a Science Fiction Cinema,” Science Fiction Studies 25.2, no. 75, 1998. ↵

A niche or specialized segment of a larger literary or filmic genre.

A subgenre of SF focused on military life and structures in interplanetary and intergalactic settings.

“The good old stuff;” a subgenre of SF with epic adventure against an intergalactic backdrop.

The development and study of feedback systems between organisms and machines.

Any intelligent robot, computer, etc.

The post-WWII period, when science fiction moved from the obscure pages of pulp magazines to the silver screen.

A term usually designating pre-Enlightenment forms of science fiction; makes assumptive value judgements based upon non-literary characteristics (relation to modern science).

The moment artificial intelligence exceeds human intelligence. See: Singularity.

Literally, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; a method of gene transformation.

Fictions—usually popular genres—named after the cheap paper on which they were published.

Literary genres consumed primarily for entertainment, often found in grocery store aisles and in mass paperback formats.

The often-denigrated urge to escape one’s present reality through fiction.

Used to describe a city or nation comprised of people from many different sociological backgrounds.

A movement in SF during the 60s and 70s that emphasized the experience of the subject through a focus on character; started by Michael Moorcock, editor of New Worlds.

An experimental and aleatory form of art that blurs the lines between reality, dream, hallucination, and fantasy.

Science fiction that relies upon the so-called “soft” sciences.

Science fiction works that emphasize the so-called “hard” sciences.

A subgenre of SF/F that focuses on the experiences of those in the African diaspora, especially that of African-Americans.

SF that forgegrounds the experiences of women.

SF that emphasizes the experience of LGBTQ peoples.

The part of the world where English is widely spoken.

A unique genre in the mimetic mode, often associated with the global south; in it, the supernatural is real and commonplace, giving such elements and air of verisimilitude without the feelings of horror or doubt so often associated with the fantastic mode.

A fascination with other cultures, usually based in stereotype and appropriation.

SF that focuses on the experiences of formerly colonized peoples.

The East Asian cultural sphere that includes Chine, Japan, and Korea.

A type of sequential art originating in Japan, usually read right to left.

A plural for medium (also media), indicating different forms in which information is transmitted.

Art, such as comic books, that is meant to be viewed in corerct order to reveal the narrative.

A form of sequential art, usually short and episodic.

A full-length work of sequential art.

Any film with a distinguishable narrative arc.

Film effects created during the production phase, captured directly by the camera.

Film effects added in the post-production phase.

Excessive nationalism and militarism. See: Militarism.

A movement in film and the arts originating in post-WWI Germany.

Literally computer-generated-images; a type of special effect in film produced through digital means.

A two-dimensional side-angle video game that moves from left to right across the screen.

The process of creating new worlds in science fiction and fantasy, a function of the virtual mode.

Games where the player adopts an avatar and plays as that character for the duration of the narrative.

A genre of book which prompts the reader with choices at certain narrative junctures, allowing for multiple endings.