Observation: Looking at the Pieces and Generating Ideas

Dorothy Todd; Sarah LeMire; Terri Pantuso; and Claire Carly-Miles

The following strategies (used either individually or together) can help you generate ideas for the focus of your paper, identify potential evidence for your argument, and begin to develop an organizational structure for your essay. Because these techniques usually occur preliminary to drafting an essay, they are called prewriting techniques; however because all writing is recursive, these strategies will recur and be useful during later stages, as well.

For all of the following strategies, write down as many ideas as you can and as quickly as you can. Don’t judge the ideas based on their quality; just focus on coming up with as many as possible. All of the following techniques work well in groups or on your own.

The Five W’s

One of the easiest ways to begin coming up with ideas to write about is by asking and answering basic questions: Who? What? Where? When? Why? These are the five W’s (also known as “reporter’s questions”), and while the answers to theme may seems obvious, you may be surprised at how helpful it can be to have those answers written down all in one place where you can see them all together, as well as how useful it may be to visualize these things in relation to one another. For instance, let’s apply the five W’s to Frankenstein.

Table 7.2. Frankenstein and the application of the five W’s.

| Who? | Characters: Victor Frankenstein, Robert Walton, Margaret Saville, Elizabeth Lavenza, Victor’s Father, Victor’s Mother, Henry Clerval, The Creature (Demon, Monster), William Frankenstein, Justine Moritz, De Lacey family (father, Felix, Agatha, Safie), M. Waldman, M. Krempe Author: Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley |

| What? | Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus Letters, written by Walton to his sister, containing Walton’s first-person narrative and his remembered transcriptions of both Victor’s and the Creature’s narratives. |

| Where? | Italy, Switzerland, Germany, England, Scotland, et. al. |

| When? | Written in 1816; published in 1818; revised edition published in 1832 Set in the 18th Century (the first letter is dated “17—”) |

| Why? | Great question! What are your thoughts? What themes surface as you read? Why does Victor do what he does? Why does the Creature do what he does? Why do you think Mary Shelley wrote this novel? As you know or will soon find out, there are many possible ways to answer these questions. |

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a general term where a writer jots down separate ideas about a topic as those ideas pop into their mind. There are no criteria; the writer simply lists ideas for topics. An example of what this might look like follows:

Frankenstein, creature, monster, science, scientist, childbirth, women, depression, post-partum depression, madness, delusions, delusional, hysteria, hyster, hysterectomy, uterus, reproduction, creation, motherhood, parenting, et. al..

Freewriting

Freewriting resembles a kind of stream-of-consciousness exercise in which you give yourself about 5-10 minutes to write down, without pausing, any and all of your thoughts about your potential topic. Don’t worry about spelling, punctuation, grammar, or any rules. Your goal is to put your ideas onto paper immediately as they occur to you. This is different from brainstorming because you are writing one nonstop “sentence” rather than a list of words. An example follows:

Frankenstein is a scientist which is interesting considering that we always hear the Creature referred to as Frankenstein in the movies so there’s this interesting blurring or confusing between creator and creature the word creature makes me think of something that exists that isn’t related to me but Victor wants the Creature to look like a man and be grateful to him for creating him but then Victor abandons his creation and what does that mean to create something and then just leave it so is the Creature the way he is because he’s unnatural or because he’s never been helped or loved and what does that say about science and parenting and when I think of that i also think about the way Victor loses his own mom early on and the relationship he has with really the only other woman in the novel Elizabeth Lavenza

Notice in this freewriting example that the writer begins in one place and ends up somewhere else entirely, jotting down pretty much whatever comes to mind. This technique generates a number of ideas (creator/creature confusion; playing god; neglectful parenting; nature vs. nurture; Victor’s relationship to women) that the writer may then choose to explore further.

Word Maps

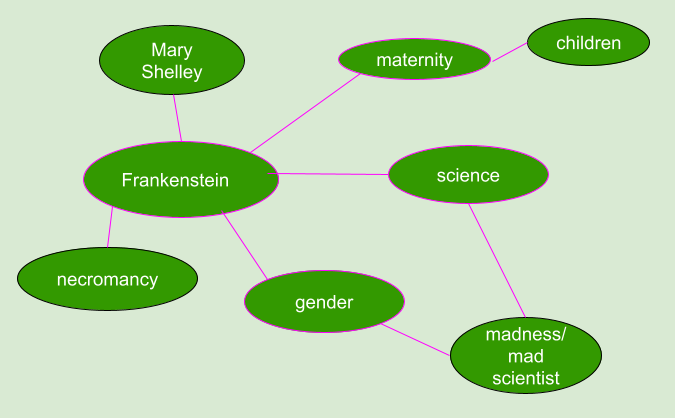

Word maps (also called webbing, clustering, or branching) involve a different kind of brainstorming. Select 2-3 words that you feel are central to your topic. Write each one in the middle of a page and draw a circle around it. As you think about each word individually, write other ideas that relate to it around your central topic and draw circles around the branching ideas. Connect them with lines to the center/central topic. You might write words or phrases on the lines that give you a sense of how topics relate to one another and to the central topic.This visual method of generating ideas may lead you to visualize connections between ideas, and this, in turn, may lead you to develop a working thesis.

As you list ideas and start thinking about connections between words and concepts, you might find yourself moving from a broad set of ideas (gender in Frankenstein) to a more narrow focus that would be an appropriate topic for an essay (considering how the presentation of gender in Frankenstein informs our understanding of science and its pitfalls). Notice how this word map also reveals how open-ended a potential topic could be. A writer could have started out with the same topic—gender in Frankenstein—and moved in an entirely different direction, perhaps thinking about depictions of childhood or about how Mary Shelley’s own life experiences may have influenced her writing.

Key Concepts, Synonyms, and Antonyms

Pick a key word, concept, idea, or theme from the text. Write down possible synonyms and antonyms for your chosen word or concept. This technique can help you make previously unnoticed connections across a text and can even help you identify potential search terms before you delve into research. Take a look at Table 7.4 below for an idea of how this strategy might work.

Table 7.3. Key Concepts, Synonyms, and Antonyms

| Key Concept | Synonyms | Antonyms |

|---|---|---|

| Science | Scientific Revolution; Enlightenment; scientific method: examination, observation, hypothesis, testing and proving; knowledge; insight; information, | Superstition; bias; prejudice; ignorance; not factual; unprovable; unethical; dangerous |

| Parent | Caretaker, mother, father, adult, responsible | Child, childhood, innocence, dependent |

| Maternal | childbirth, caretaker, comforter, teacher | neglectful, distant, unapproachable, cold |

| Demon | Satan, evil, nemesis, enemy, malevolent, antagonist, villain | God, angel, benefactor, benevolent, protagonist, hero |

Venn Diagrams

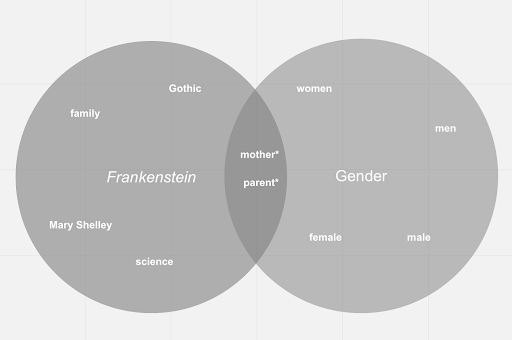

Venn Diagrams help us establish where two terms may have something in common or overlap with one another. Let’s say you’re interested in gender in Frankenstein. Write “Frankenstein” in the first circle and then jot down ideas related to the novel (or the character) around that main topic. In the second circle, write down the word “gender” and then brainstorm other related terms, such as sexuality or women, to support or narrow down your topic, as is depicted in Figure 7.5.

As you list terms, you may find that there is a concept that piques your interest. For instance, perhaps the idea of gender roles (men, women, male, female) in Frankenstein seems interesting. You could then use this topic for your essay. Even further, you may find terms that fit into the overlapping area of the two circles. Here we’ve identified the concepts of motherhood and parenting, both of which appear in the novel and involve gender roles. As a result, these concepts will not only help you find a topic upon which to write, but they will also provide you with some possible search terms to use when you begin to look for scholarship on your topic. You may have noticed that we’ve used an asterisk to truncate each term, in preparation for using them as search terms; we will discuss this tool in more detail below in “Discovery and Exploration: Finding and Using Specific Sources.”

Hypothesis

After you’ve tried some (or all) of the preceding idea-generating strategies, it’s time to hypothesize. A “hypothesis” is, of course, a scientific concept, and therefore it may not be much of a surprise to find it in a textbook about science fiction and fantasy. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a hypothesis is “an idea or explanation for something that may be true but has not yet been completely proved.”[1] Consider now what you’ve probably learned in any English or composition class you’ve ever taken: every essay needs a thesis (a main argument or claim) that the body of that essay will then prove. Much like a hypothesis, “an idea that may be true but has not been completing proved,” your thesis is something you’ve created based on your observations (and on your idea-generating exercises) and that you will then need to prove by martialing evidence (quotations from the text, other primary sources, and secondary sources) to support your argument,

At this stage in the writing process, you will want to begin to look more closely at potential connections and patterns. Consider how each of the strategies above led us to consider something new or more complex about Frankenstein. From the Five W’s, we began to think about characters, contexts, and themes. Brainstorming, freewriting, and word mapping helped us generate a number of key words and concepts that we may then plug into Venn diagrams to see even more connections and overlapping ideas.

Once you have all of this excellent material circulating in your brain, you can begin to think about a working (tentative) thesis for your essay. You can do this via several different methods, and those methods may be performed (and revisited) in many different orders. Before we move on to discussing the different parts of an essay and how we might approach writing these, however, let’s take a look at finding, reading, and engaging with sources, both secondary and additional primary sources. Please note: all the steps we have discussed or have yet to discuss will occur and recur at many different stages in our writing, so just because we place the following sections between generating ideas and beginning to write, this doesn’t mean that discovery and exploration of secondary sources is limited to this spot in the process.

Attribution:

Carly-Miles, Claire. “Observation: Looking at the Pieces and Generating Ideas.” In Marvels and Wonders: Reading, Researching, and Writing about SF/F. 1st Edition. Edited by R. Paul Cooper, Claire Carly-Miles, Kalani Pattison, Jeremy Brett, Melissa McCoul, and James Francis, Jr. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2022. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Todd, Dorothy, Sarah LeMire, James Sexton, and Derek Soles. “Writing a Literary Essay: Moving from Surface to Subtext: Generating Ideas.” In Surface and Subtext: Literature, Research, Writing. Pilot ed. Edited by Claire Carly-Miles, Sarah LeMire, Kathy Christie Anders, Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, R. Paul Cooper, and Matt McKinney. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Sexton, James, and Derek Soles. Composition and Literature. Victoria, B.C.: BCcampus, 2019. https://opentextbc.ca/provincialenglish/chapter/access-and-acquire-knowledge/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/hypothesis ↵

Techniques, such as free-writing, that prepare prime your thinking.

Who; What; When; Where; How; and Why.