8.4 Law of Sines

In this section, we showcase how the the tools we’ve developed in Chapters 7 and 8 can be applied to Geometry. Our next two sections focus specifically on solving oblique (non-right) Triangles.[1]

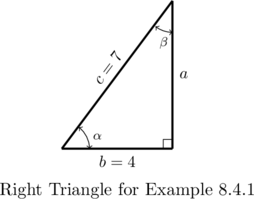

Our first example reviews the basics of right triangle trigonometry. The reader is referred to Section 7.2.1 for more details and practice with these concepts.

Example 8.4.1

Example 8.4.1.1

Given a right triangle with a hypotenuse of length 7 units and one leg of length 4 units, compute the length of the remaining side and the measures of the remaining angles. Express the angles in decimal degrees, rounded to the nearest hundredth of a degree.

Solution:

For definitiveness, we label the triangle below.

To find ![]() , we use the Pythagorean Theorem, Theorem 7.1:

, we use the Pythagorean Theorem, Theorem 7.1:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} a^2 + 4^2 & &= 7^2 \\[4pt] a^2 & = & 33 \\[4pt] a &=& \sqrt{33} \text{ units } \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-17cd35cc49e96b3a333a2815454f2e92_l3.png)

Now that all three sides of the triangle are known, there are several ways we can find ![]() using the inverse trigonometric functions.

using the inverse trigonometric functions.

To decrease the chances of propagating error, however, we stick to using the data given to us in the problem. In this case, the lengths ![]() and

and ![]() were given, so we want to relate these to

were given, so we want to relate these to ![]() .

.

According to Definition 7.2, ![]() . As

. As ![]() is an acute angle,

is an acute angle,

![]()

Now that we have the measure of angle ![]() , we could find the measure of angle

, we could find the measure of angle ![]() using the fact that

using the fact that ![]() and

and ![]() are complements so

are complements so ![]() .

.

Once again, in the interests of minimizing propagated error, we opt to use the data given to us in the problem. According to Definition 7.2, ![]() so

so

![]()

A few remarks about Example 8.4.1 are in order. First, we adhere to the convention that a lower case Greek letter denotes an angle (as well as the measure of said angle) and the corresponding lowercase English letter represents the side (as well as the length of said side) opposite that angle.

More specifically, ![]() is the side opposite

is the side opposite ![]() ,

, ![]() is the side opposite

is the side opposite ![]() and

and ![]() is the side opposite

is the side opposite ![]() . Taken together, the pairs

. Taken together, the pairs ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are called angle-side opposite pairs.

are called angle-side opposite pairs.

Second, as mentioned earlier, we will strive to solve for quantities using the original data given in the problem whenever possible. While this is not always the easiest or fastest way to proceed, it minimizes the chances of propagated error.[2]

Third, as many of the applications which require solving triangles `in the wild’ rely on degree measure, we shall adopt this convention for the time being.

The Pythagorean Theorem along with Definition 7.2 allow us to easily handle any given right triangle problem, but what if the triangle isn’t a right triangle? In certain cases, we can use the Law of Sines.

Theorem 8.15 The Law of Sines

Given a triangle with angle-side opposite pairs ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , the following ratios hold:

, the following ratios hold:

![]()

or, equivalently,

![]()

The proof of the Law of Sines can be broken into three cases, and, as we’ll see, ultimately relies on what we know about right triangles.

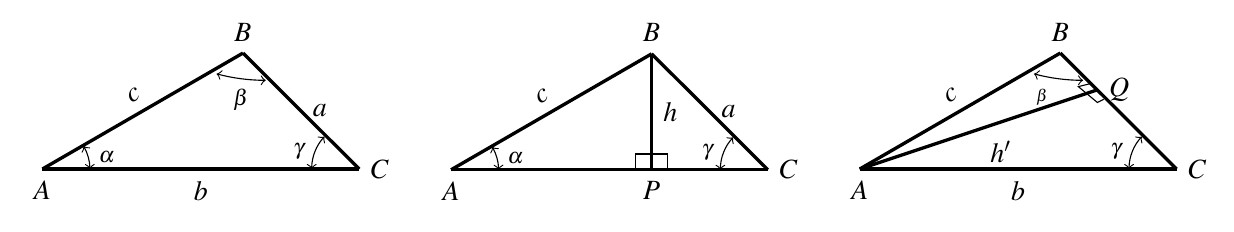

For our first case, consider the triangle ![]() below, all of whose angles are acute, with angle-side opposite pairs

below, all of whose angles are acute, with angle-side opposite pairs ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

If we drop an altitude from vertex ![]() , we divide the triangle into two right triangles:

, we divide the triangle into two right triangles: ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

If we call the length of the altitude ![]() (for height), we get from Definition 7.2 that

(for height), we get from Definition 7.2 that ![]() and

and ![]() so that

so that ![]() . Rearranging this last equation, we get

. Rearranging this last equation, we get ![]() .

.

Dropping an altitude from vertex ![]() , we can proceed as above using the triangles

, we can proceed as above using the triangles ![]() and

and ![]() . We find that

. We find that ![]() , so we have shown

, so we have shown ![]() as required.

as required.

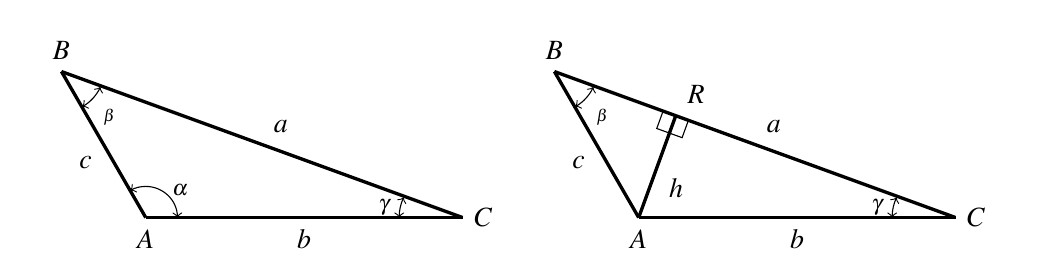

For our next case consider the triangle ![]() below with obtuse angle

below with obtuse angle ![]() .

.

Extending an altitude from vertex ![]() gives two right triangles, as in the previous case:

gives two right triangles, as in the previous case: ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Proceeding as before, we get ![]() and

and ![]() so that

so that ![]() .

.

Dropping an altitude from vertex B also generates two right triangles, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We see ![]() so that

so that ![]() . Because

. Because ![]() ,

, ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

Proceeding to ![]() , we get

, we get ![]() so

so ![]() .

.

As before, we get ![]() , so

, so ![]() in this case, too.

in this case, too.

The remaining case is when ![]() is a right triangle. In this case, the Law of Sines reduces to the formulas given in Definition 7.2 and is left to the reader.

is a right triangle. In this case, the Law of Sines reduces to the formulas given in Definition 7.2 and is left to the reader.

In order to use the Law of Sines to solve a triangle, we need at least one angle-side opposite pair. The next example showcases some of the power, and the pitfalls, of the Law of Sines.

Example 8.4.2

Example 8.4.2.1

Solve the following triangles. Give exact answers and decimal approximations (rounded to hundredths) and then sketch the triangle.

![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]()

Solution:

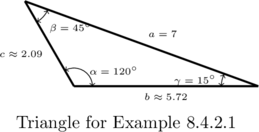

Solve the triangle with the properties: ![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() .

.

Knowing an angle-side opposite pair, namely ![]() and

and ![]() , we may proceed in using the Law of Sines.

, we may proceed in using the Law of Sines.

Given ![]() , we use

, we use

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{b}{\sin\left(45^{\circ}\right)} &=& \frac{7}{\sin\left(120^{\circ}\right)} \\[10pt] b &=& \frac{7\sin\left(45^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(120^{\circ}\right)}\\[10pt] &=& \frac{7\sqrt{6}}{3} \\[10pt] &\approx& 5.72 \text{ units} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-50677cb9f98f992a5e259f546b9eb3f6_l3.png)

To find ![]() , we use the fact that the sum of the measures of the angles in a triangle is

, we use the fact that the sum of the measures of the angles in a triangle is ![]() . Hence,

. Hence,

![]()

To find ![]() , we have no choice but to used the derived value

, we have no choice but to used the derived value ![]() , yet we can minimize the propagation of error here by using the given angle-side opposite pair

, yet we can minimize the propagation of error here by using the given angle-side opposite pair ![]() .

.

The Law of Sines gives us[3]

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{c}{\sin\left(15^{\circ}\right)} &=& \frac{7}{\sin\left(120^{\circ}\right)}\\[10pt] c &=& \frac{7\sin\left(15^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(120^{\circ}\right)} \\[10pt] &\approx& 2.09 \text{ units} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-ed9b48d1cddb61eb8b85040a1ad4cdd3_l3.png)

We sketch this triangle below.

Example 8.4.2.2

Solve the following triangles. Give exact answers and decimal approximations (rounded to hundredths) and then sketch the triangle.

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() units

units

Solution:

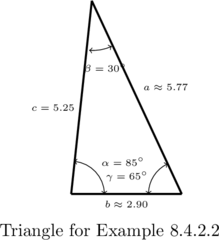

Solve the triangle with the properties: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() units.

units.

In this example, we are not immediately given an angle-side opposite pair, but as we have the measures of ![]() and

and ![]() , we can solve for

, we can solve for ![]() giving us

giving us

![]()

As in the previous example, we are forced to use a derived value in our computations because the only angle-side pair available is ![]() .

.

The Law of Sines gives

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{a}{\sin\left(85^{\circ}\right)} &=& \frac{5.25}{\sin\left(65^{\circ}\right)}\\[10pt] a &=& \frac{5.25\sin\left(85^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(65^{\circ}\right)} \\[10pt] &\approx & 5.77 \text{ units } \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-b7b0977963dcc3ce3c4861203184ce9e_l3.png)

To find ![]() we use the angle-side pair

we use the angle-side pair ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{b}{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)} &=& \frac{5.25}{\sin\left(65^{\circ}\right)}\\[10pt] b &=& \frac{5.25\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(65^{\circ}\right)} \\[10pt] &\approx& 2.90 \text{ units} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-14e58051ed2fdf2dc2512bc65d4ccf31_l3.png)

Next, we sketch this triangle.

Example 8.4.2.3

Solve the following triangles. Give exact answers and decimal approximations (rounded to hundredths) and then sketch the triangle.

![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units

units

Solution:

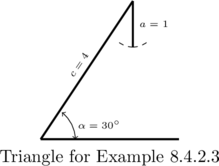

Solve the triangle with the properties: ![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units.

units.

We are given ![]() and

and ![]() , so we use the Law of Sines to find the measure of

, so we use the Law of Sines to find the measure of ![]() .

.

From

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{\sin(\gamma)}{4} &=& \frac{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}{1} \\[10pt] \sin(\gamma) &=& 4 \sin\left(30^{\circ}\right) \\[10pt] &=& 2 \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-6f13639f4cbac958e309653f794640ea_l3.png)

which is impossible. (Why?) As seen below, side ![]() is just too short to make a triangle.

is just too short to make a triangle.

The next three examples keep the same values for the measure of ![]() and the length of

and the length of ![]() while varying the length of

while varying the length of ![]() . We will discuss this case in more detail after we see what happens in those examples.

. We will discuss this case in more detail after we see what happens in those examples.

Example 8.4.2.4

Solve the following triangles. Give exact answers and decimal approximations (rounded to hundredths) and then sketch the triangle.

![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units

units

Solution:

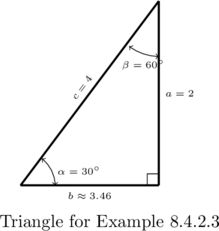

Solve the triangle with the properties:![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units.

units.

In this case, we have the measure of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . Using the Law of Sines, we get

. Using the Law of Sines, we get

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{\sin(\gamma)}{4} &=& \frac{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}{2} \\[10pt] \sin(\gamma) &=& 2 \sin\left(30^{\circ}\right) \\[10pt] &=& 1 \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-112d520e1c00c15263d20e903cf14b04_l3.png)

As ![]() is an angle in a triangle which also contains

is an angle in a triangle which also contains ![]() ,

, ![]() must measure between

must measure between ![]() and

and ![]() in order to fit inside the triangle with

in order to fit inside the triangle with ![]() . The only angle that satisfies this requirement and has

. The only angle that satisfies this requirement and has ![]() is

is ![]() , so we are working in a right triangle.

, so we are working in a right triangle.

We find the measure of ![]() to be

to be

![]()

. Using the Law of Sines, we get

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} b &=& \frac{2 \sin\left(60^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}\\[10pt] &=& 2 \sqrt{3} \\[10pt] &\approx & 3.46 \text{ units} \end{array}\]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-14296c1b744a7207e45da31d200c4f3e_l3.png)

As seen below, the side ![]() is just long enough to form a right triangle in this case.

is just long enough to form a right triangle in this case.

Example 8.4.2.5

Solve the following triangles. Give exact answers and decimal approximations (rounded to hundredths) and then sketch the triangle.

![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units

units

Solution:

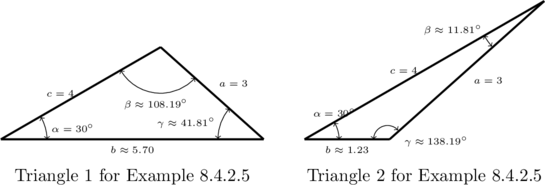

Solve the triangle with the properties: ![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units.

units.

Proceeding as we have in the previous two examples, we use the Law of Sines to find ![]() .

.

In this case, we have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{\sin(\gamma)}{4} &=& \frac{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}{3}\\[10pt] \sin(\gamma) &=& \frac{4\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}{3} \\[10pt] &=& \frac{2}{3} \end{array}\]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-e136ad8f560bc5ff073a68e38b2338ba_l3.png)

As ![]() lies in a triangle with

lies in a triangle with ![]() , we must have that

, we must have that ![]() .

.

In this case, there are two angles that fall in this range:

![]()

\begin{center} and \end{center}

![]()

At this point, we pause to see if it makes sense that we have two cases to consider.

As ![]() , it must also be true that

, it must also be true that ![]() , which is opposite

, which is opposite ![]() , has greater measure than

, has greater measure than ![]() which is opposite

which is opposite ![]() . In both cases,

. In both cases, ![]() , so both candidates for

, so both candidates for ![]() make sense with the given value of

make sense with the given value of ![]() .

.

Thus have two triangles on our hands. In the case

![]()

we find[4]

![]()

The Law of Sines with the angle-side opposite pair ![]() and

and ![]() gives

gives

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} b &\approx & \frac{3 \sin\left(108.19^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)} \\[10pt] &\approx & 5.70 \text{ units} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-2bfeee28bc8a7cd3e4b9ea7d04709791_l3.png)

We sketch this triangle below on the left.

In the case ![]() radians

radians ![]() , we repeat the same steps and find

, we repeat the same steps and find ![]() and

and ![]() units.[5] We sketch this triangle below on the right.

units.[5] We sketch this triangle below on the right.

Example 8.4.2.6

Solve the following triangles. Give exact answers and decimal approximations (rounded to hundredths) and then sketch the triangle.

![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units

units

Solution:

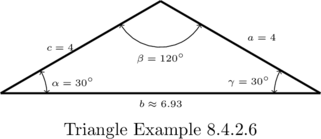

Solve the triangle with the properties: ![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() units.

units.

For this last problem, we repeat the usual Law of Sines routine to find that

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{\sin(\gamma)}{4} &=& \frac{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}{4} \\[10pt] \sin(\gamma) &=& \frac{1}{2} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-ed2d2b21a9afd1090787e63e00bd915b_l3.png)

As ![]() must inhabit a triangle with

must inhabit a triangle with ![]() , we must have

, we must have ![]() .

.

Because the measure of ![]() must be strictly less than

must be strictly less than ![]() , there is just one angle which satisfies both required conditions, namely

, there is just one angle which satisfies both required conditions, namely ![]() .

.

Hence,

![]()

The Law of Sines gives

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} b &=& \frac{4\sin\left(120^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}\\[10pt] &=& 4\sqrt{3} \\[10pt] &\approx & 6.93 \text{ units} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-02b4118fcf93cc15c255f91995663dfc_l3.png)

We sketch this triangle below.

Some remarks about Example 8.4.2 are in order. First note that if we are given the measures of two of the angles in a triangle, say ![]() and

and ![]() , the measure of the third angle

, the measure of the third angle ![]() is uniquely determined using the equation

is uniquely determined using the equation ![]() . Knowing the measures of all three angles of a triangle completely determines the triangle’s shape.

. Knowing the measures of all three angles of a triangle completely determines the triangle’s shape.

If in addition we are given the length of one of the sides of the triangle, we can then use the Law of Sines to find the lengths of the remaining two sides to determine the size of the triangle. Such is the case in numbers 1 and 2 above.

In number 1, the given side is adjacent to just one of the angles — this is called the `Angle-Angle-Side’ (AAS) case.[6] In number 2, the given side is adjacent to both angles which means we are in the so-called `Angle-Side-Angle’ (ASA) case.

If, on the other hand, we are given the measure of just one of the angles in the triangle along with the length of two sides, only one of which is adjacent to the given angle, we are in the `Side-Side-Angle’ (SSA) case. Such was the case in numbers 3, 4, 5, and 6 above.

In number 3, the length of the one given side ![]() was too short to even form a triangle; in number 4, the length of

was too short to even form a triangle; in number 4, the length of ![]() was just long enough to form a right triangle; in 5,

was just long enough to form a right triangle; in 5, ![]() was long enough, but not too long, so that two triangles were possible; and in number 6, side

was long enough, but not too long, so that two triangles were possible; and in number 6, side ![]() was long enough to form a triangle but too long to swing back and form two. These four cases exemplify all of the possibilities in the Angle-Side-Side case which are summarized in the following theorem.

was long enough to form a triangle but too long to swing back and form two. These four cases exemplify all of the possibilities in the Angle-Side-Side case which are summarized in the following theorem.

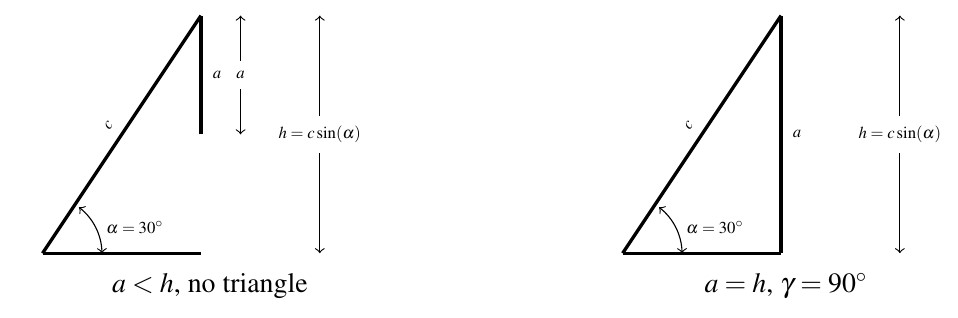

Theorem 8.16

Suppose ![]() and

and ![]() are intended to be angle-side pairs in a triangle where

are intended to be angle-side pairs in a triangle where ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are given. Let

are given. Let ![]()

- If

, then no triangle exists which satisfies the given criteria.

, then no triangle exists which satisfies the given criteria. - If

, then

, then  so exactly one (right) triangle exists which satisfies the criteria.

so exactly one (right) triangle exists which satisfies the criteria. - If

, then two distinct triangles exist which satisfy the given criteria.

, then two distinct triangles exist which satisfy the given criteria. - If

, then

, then  is acute and exactly one triangle exists which satisfies the given criteria

is acute and exactly one triangle exists which satisfies the given criteria

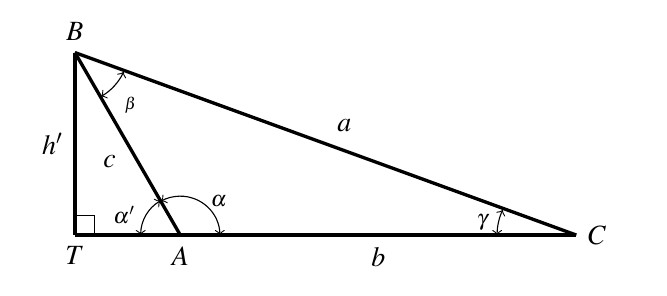

Theorem 8.16 is proved on a case-by-case basis. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . If a triangle were to exist, the Law of Sines would have

. If a triangle were to exist, the Law of Sines would have ![]() so that

so that ![]() , which is impossible.

, which is impossible.

In the figure below on the left, we see geometrically why this is the case. Simply put, if ![]() , the side

, the side ![]() is too short to connect to form a triangle.

is too short to connect to form a triangle.

This means if ![]() , we are always guaranteed to have at least one triangle, and the remaining parts of the theorem tell us what kind and how many triangles to expect in each case.

, we are always guaranteed to have at least one triangle, and the remaining parts of the theorem tell us what kind and how many triangles to expect in each case.

If ![]() , then

, then ![]() and the Law of Sines gives

and the Law of Sines gives ![]() so that

so that ![]() . Here,

. Here, ![]() as required. This situation is sketched below on the right.

as required. This situation is sketched below on the right.

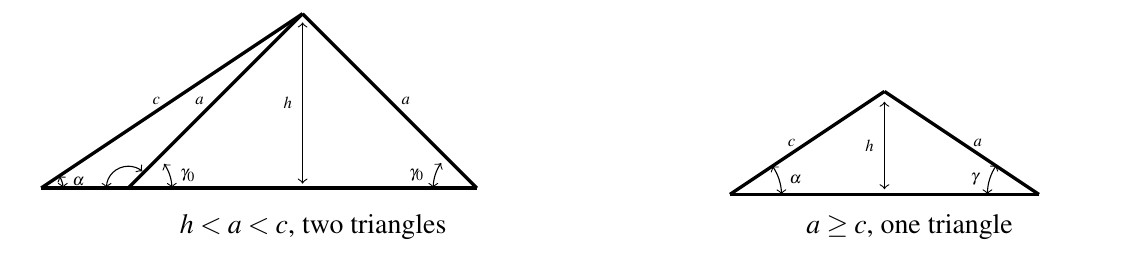

Moving along, now suppose ![]() . As before, the Law of Sines[7] gives

. As before, the Law of Sines[7] gives ![]() .

.

As ![]() ,

, ![]() or

or ![]() which means there are two solutions to

which means there are two solutions to ![]() : an acute angle which we’ll call

: an acute angle which we’ll call ![]() , and its supplement,

, and its supplement, ![]() .

.

Our job now is to argue that each of these angles `fit’ into a triangle with ![]() . Given

. Given ![]() and

and ![]() are angle-side opposite pairs, the assumption

are angle-side opposite pairs, the assumption ![]() in this case gives us

in this case gives us ![]() . Because

. Because ![]() is acute, we must have that

is acute, we must have that ![]() is acute as well. This means one triangle can contain both

is acute as well. This means one triangle can contain both ![]() and

and ![]() , giving us one of the triangles promised in the theorem.

, giving us one of the triangles promised in the theorem.

If we manipulate the inequality ![]() a bit, we have

a bit, we have ![]() . Adding

. Adding ![]() to both sides gives

to both sides gives ![]() . This proves a triangle can contain both of the angles

. This proves a triangle can contain both of the angles ![]() and

and ![]() , giving us the second triangle predicted in the theorem. We sketch the two triangle case below on the left.

, giving us the second triangle predicted in the theorem. We sketch the two triangle case below on the left.

To prove the last case in the theorem, we assume ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() , which forces

, which forces ![]() to be an acute angle. Hence, we get only one triangle in this case, completing the proof.

to be an acute angle. Hence, we get only one triangle in this case, completing the proof.

One last comment regarding the Angle-Side-Side case: if you are given an obtuse angle to begin with then it is impossible to have the two triangle case. Think about this before reading further.

In many of the derivations and arguments in this section, we used the height of a given triangle, ![]() , as an intermediate variable to prove equivalences. The height of a triangle can be used to determine the area enclosed by said triangle, thus we can use the methods in this section to reformulate area in terms of side lengths and sines of angles. We state the following theorem and leave its proof as an exercise.

, as an intermediate variable to prove equivalences. The height of a triangle can be used to determine the area enclosed by said triangle, thus we can use the methods in this section to reformulate area in terms of side lengths and sines of angles. We state the following theorem and leave its proof as an exercise.

Theorem 8.17

Suppose ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are the angle-side opposite pairs of a triangle. Then the area

are the angle-side opposite pairs of a triangle. Then the area ![]() enclosed by the triangle is given by

enclosed by the triangle is given by

![]()

That is, the area enclosed by the triangle ![]()

Example 8.4.3

Example 8.4.3

Compute the area of the triangle in Example 8.4.2 number 1. Recall: ![]() ,

, ![]() units,

units, ![]() .

.

Solution:

From our work in Example 8.4.2 number 1, we have all three angles and all three sides to work with. However, to minimize propagated error, we choose ![]() from Theorem 8.17 because it uses the most pieces of given information.

from Theorem 8.17 because it uses the most pieces of given information.

We are given ![]() and

and ![]() , and we calculated

, and we calculated ![]() .

.

Using these values, we find the area

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} A &=& \frac{1}{2}(7)\left(\frac{7\sin\left(15^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(120^{\circ}\right)} \right) \sin\left(45^{\circ}\right) \\[10pt] &\approx & 5.18 \text{ square units} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-0147d364ec6bb41910494b92df79fe55_l3.png)

The reader is encouraged to check this answer against the results obtained using the other formulas in Theorem 8.17.

8.4.1 Bearings

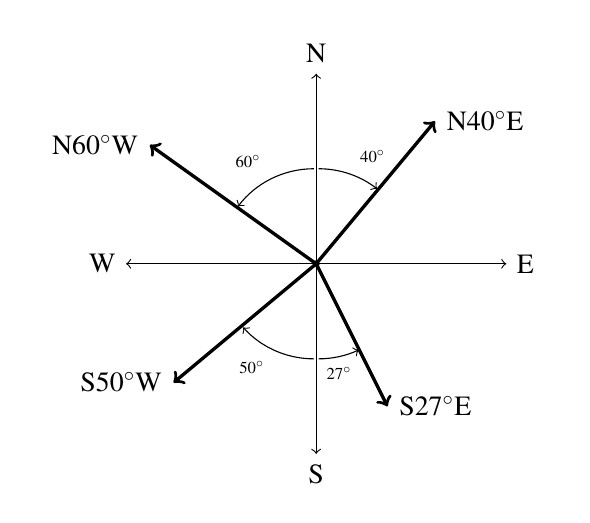

Our last example of the section uses the navigation tool known as bearings. Simply put, a bearing is the direction you are heading according to a compass.

The classic nomenclature for bearings, however, is not given as an angle in standard position, so we must first understand the notation. A bearing is given as an acute angle of rotation (to the east or to the west) away from the north-south (up and down) line of a compass rose.

For example, N![]() E (read “

E (read “![]() east of north”) is a bearing which is rotated clockwise

east of north”) is a bearing which is rotated clockwise ![]() from due north. If we imagine standing at the origin in the Cartesian Plane, this bearing would have us heading into Quadrant I along the terminal side of

from due north. If we imagine standing at the origin in the Cartesian Plane, this bearing would have us heading into Quadrant I along the terminal side of ![]()

Similarly, S![]() W would point into Quadrant III along the terminal side of

W would point into Quadrant III along the terminal side of ![]() because we started out pointing due south (along

because we started out pointing due south (along ![]() ) and rotated clockwise

) and rotated clockwise ![]() back to

back to ![]()

Counter-clockwise rotations would be found in the bearings N![]() W (which is on the terminal side of

W (which is on the terminal side of ![]() ) and S

) and S![]() E (which lies along the terminal side of

E (which lies along the terminal side of ![]() ).

).

These four bearings are sketched in the plane below.

The cardinal directions north, south, east and west are usually not given as bearings in the fashion described above, but rather, one just refers to them as `due north’, `due south’, `due east’ and `due west’, respectively, and it is assumed that you know which quadrantal angle goes with each cardinal direction.

We make good use of bearings and the Law of Sines in our next example.

Example 8.4.4

Example 8.4.4

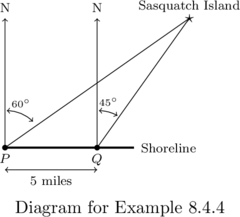

Sasquatch Island lies off the coast of Ippizuti Lake. As illustrated below, from a point ![]() on the shore, the bearing to Sasquatch Island is observed to be N

on the shore, the bearing to Sasquatch Island is observed to be N![]() E. From a point

E. From a point ![]() that is 5 miles due East of

that is 5 miles due East of ![]() , the bearing to the island is observed to be N

, the bearing to the island is observed to be N![]() E.

E.

Assuming the coastline continues to run due East, find the distance from the point ![]() to the island. What point on the shore is closest to the island? How far is the island from this point?

to the island. What point on the shore is closest to the island? How far is the island from this point?

Solution:

As illustrated above, the points ![]() ,

, ![]() , and the location of the island (represented as a point) form a triangle. Using the bearings information given, we get that the angle between the shore and the island at point

, and the location of the island (represented as a point) form a triangle. Using the bearings information given, we get that the angle between the shore and the island at point ![]() is

is

![]()

while the angle between the shore and the island at point ![]() is

is

![]()

We pause for a moment to summarize our known (and label our unknown) information below.

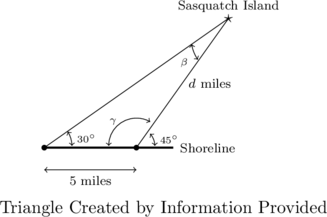

In order to use the Law of Sines to find the distance ![]() from

from ![]() to the island, we first need to find the measure of

to the island, we first need to find the measure of ![]() which is the angle opposite the side of length

which is the angle opposite the side of length ![]() miles.

miles.

As a result of the angles ![]() and

and ![]() being supplemental, we get

being supplemental, we get

![]()

Knowing ![]() , we now find

, we now find

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \beta &=& 180^{\circ} - 30^{\circ} - \gamma \\[4pt] &=& 180^{\circ} - 30^{\circ} - 135^{\circ} \\[4pt] &=& 15^{\circ} \end{array}\]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-48346a896fe54d34764ea6475c3b9e06_l3.png)

By the Law of Sines, we have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \frac{d}{\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)} &=& \frac{5}{\sin\left(15^{\circ}\right)} \\[10pt] d &=& \frac{5\sin\left(30^{\circ}\right)}{\sin\left(15^{\circ}\right)} \\[10pt] &\approx & 9.66 \text{ miles} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-21a213614a1857cbafa6f7cce6ab2ba6_l3.png)

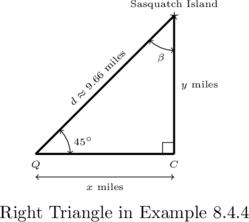

To find the point on the coast closest to the island, which we’ve labeled as ![]() in the next diagram, we need to find the perpendicular distance from the island to the coast.[8] Let

in the next diagram, we need to find the perpendicular distance from the island to the coast.[8] Let ![]() denote the distance from the second observation point

denote the distance from the second observation point ![]() to the point

to the point ![]() and let

and let ![]() denote the distance from

denote the distance from ![]() to the island.

to the island.

Using Definition 7.2, we get

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} \sin\left(45^{\circ}\right) &=& \frac{y}{d}\\[10pt] y &=& d \sin\left(45^{\circ}\right) \\[10pt] & \approx & 9.66 \left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right) \\[10pt] & \approx& 6.83 \text{ miles} \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-9d7b14b9b66d2ea5ec5f6650a12ea049_l3.png)

Hence, the island is approximately ![]() miles from the coast.

miles from the coast.

To find the distance from ![]() to

to ![]() , we note that

, we note that

![]()

so by symmetry,[9] we get ![]() miles. Hence, the point on the shore closest to the island is approximately

miles. Hence, the point on the shore closest to the island is approximately ![]() miles down the coast from the second observation point

miles down the coast from the second observation point ![]() .

.

8.4.2 Section Exercises

In Exercises 1 – 20, solve for the remaining side(s) and angle(s) if possible. As in the text, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are angle-side opposite pairs.

are angle-side opposite pairs.

The Grade of a Road: The grade of a road is much like the pitch of a roof in that it expresses the ratio of rise/run. In the case of a road, this ratio is always positive because it is measured going uphill and it is usually given as a percentage. For example, a road which rises 7 feet for every 100 feet of (horizontal) forward progress is said to have a 7\% grade. However, if we want to apply any Trigonometry to a story problem involving roads going uphill or downhill, we need to view the grade as an angle with respect to the horizontal. In Exercises 22 – 24, we first have you change road grades into angles and then use the Law of Sines in an application.

- Using a right triangle with a horizontal leg of length 100 and vertical leg with length 7, show that a 7\% grade means that the road (hypotenuse) makes about a

angle with the horizontal. (It will not be exactly

angle with the horizontal. (It will not be exactly  , but it’s pretty close.)

, but it’s pretty close.) - What grade is given by a

angle made by the road and the horizontal?[10]

angle made by the road and the horizontal?[10] - Along a long, straight stretch of mountain road with a 7\% grade, you see a tall tree standing perfectly plumb alongside the road.[11] From a point 500 feet downhill from the tree, the angle of inclination from the road to the top of the tree is

. Use the Law of Sines to find the height of the tree. (Hint: First show that the tree makes a

. Use the Law of Sines to find the height of the tree. (Hint: First show that the tree makes a  angle with the road.)

angle with the road.)

Exercises 25 – 31 use the concept of bearings as introduced in Section 8.4.1.

- Find the angle

in standard position with

in standard position with  which corresponds to each of the bearings given below.

which corresponds to each of the bearings given below.

- due west

- S

E

E - N

E

E - due south

- N

W

W - N

E

E - S

W

W

- The Colonel spots a campfire at a of bearing N

E from his current position. Sarge, who is positioned 3000 feet due east of the Colonel, reckons the bearing to the fire to be N

E from his current position. Sarge, who is positioned 3000 feet due east of the Colonel, reckons the bearing to the fire to be N W from his current position. Determine the distance from the campfire to each man, rounded to the nearest foot.

W from his current position. Determine the distance from the campfire to each man, rounded to the nearest foot. - A hiker starts walking due west from Sasquatch Point and gets to the Chupacabra Trailhead before she realizes that she hasn’t reset her pedometer. From the Chupacabra Trailhead she hikes for 5 miles along a bearing of N

W which brings her to the Muffin Ridge Observatory. From there, she knows a bearing of S

W which brings her to the Muffin Ridge Observatory. From there, she knows a bearing of S E will take her straight back to Sasquatch Point. How far will she have to walk to get from the Muffin Ridge Observatory to Sasquatch Point? What is the distance between Sasquatch Point and the Chupacabra Trailhead?

E will take her straight back to Sasquatch Point. How far will she have to walk to get from the Muffin Ridge Observatory to Sasquatch Point? What is the distance between Sasquatch Point and the Chupacabra Trailhead? - The captain of the SS Bigfoot sees a signal flare at a bearing of N

E from her current location. From his position, the captain of the HMS Sasquatch finds the signal flare to be at a bearing of N

E from her current location. From his position, the captain of the HMS Sasquatch finds the signal flare to be at a bearing of N W. If the SS Bigfoot is 5 miles from the HMS Sasquatch and the bearing from the SS Bigfoot to the HMS Sasquatch is N

W. If the SS Bigfoot is 5 miles from the HMS Sasquatch and the bearing from the SS Bigfoot to the HMS Sasquatch is N E, find the distances from the flare to each vessel, rounded to the nearest tenth of a mile.

E, find the distances from the flare to each vessel, rounded to the nearest tenth of a mile. - Carl spies a potential Sasquatch nest at a bearing of N

E and radios Jeff, who is at a bearing of N

E and radios Jeff, who is at a bearing of N E from Carl’s position. From Jeff’s position, the nest is at a bearing of S

E from Carl’s position. From Jeff’s position, the nest is at a bearing of S W. If Jeff and Carl are 500 feet apart, how far is Jeff from the Sasquatch nest? Round your answer to the nearest foot.

W. If Jeff and Carl are 500 feet apart, how far is Jeff from the Sasquatch nest? Round your answer to the nearest foot. - A hiker determines the bearing to a lodge from her current position is S

W. She proceeds to hike 2 miles at a bearing of S

W. She proceeds to hike 2 miles at a bearing of S E at which point she determines the bearing to the lodge is S

E at which point she determines the bearing to the lodge is S W. How far is she from the lodge at this point? Round your answer to the nearest hundredth of a mile.

W. How far is she from the lodge at this point? Round your answer to the nearest hundredth of a mile. - A watchtower spots a ship off shore at a bearing of N

E. A second tower, which is 50 miles from the first at a bearing of S

E. A second tower, which is 50 miles from the first at a bearing of S E from the first tower, determines the bearing to the ship to be N

E from the first tower, determines the bearing to the ship to be N W. How far is the boat from the second tower? Round your answer to the nearest tenth of a mile.

W. How far is the boat from the second tower? Round your answer to the nearest tenth of a mile.

Exercises 32 – 33 use the concepts of `angle of inclination’ and `angle of depression’ introduced in Section 7.2.1 and Exercise 18, respectively.

- Skippy and Sally decide to hunt UFOs. One night, they position themselves 2 miles apart on an abandoned stretch of desert runway. An hour into their investigation, Skippy spies a UFO hovering over a spot on the runway directly between him and Sally. He records the angle of inclination from the ground to the craft to be

and radios Sally immediately to find the angle of inclination from her position to the craft is

and radios Sally immediately to find the angle of inclination from her position to the craft is  . How high off the ground is the UFO at this point? Round your answer to the nearest foot. (Recall: 1 mile is 5280 feet.)

. How high off the ground is the UFO at this point? Round your answer to the nearest foot. (Recall: 1 mile is 5280 feet.) - The angle of depression from an observer in an apartment complex to a gargoyle on the building next door is

. From a point five stories below the original observer, the angle of inclination to the gargoyle is

. From a point five stories below the original observer, the angle of inclination to the gargoyle is  . Find the distance from each observer to the gargoyle and the distance from the gargoyle to the apartment complex. Round your answers to the nearest foot. (Use the rule of thumb that one story of a building is 9 feet.)

. Find the distance from each observer to the gargoyle and the distance from the gargoyle to the apartment complex. Round your answers to the nearest foot. (Use the rule of thumb that one story of a building is 9 feet.) - Prove that the Law of Sines holds when

is a right triangle.

is a right triangle. - Discuss with your classmates why knowing only the three angles of a triangle is not enough to determine any of the sides.

- Discuss with your classmates why the Law of Sines cannot be used to find the angles in the triangle when only the three sides are given. Also discuss what happens if only two sides and the angle between them are given. (Said another way, explain why the Law of Sines cannot be used in the SSS and SAS cases.)

- Given

and

and  , choose four different values for

, choose four different values for  so that

so that

-

- the information yields no triangle

- the information yields exactly one right triangle

- the information yields two distinct triangles

- the information yields exactly one obtuse triangle

Explain why you cannot choose

in such a way as to have

in such a way as to have  ,

,  and your choice of

and your choice of  yield only one triangle where that unique triangle has three acute angles.

yield only one triangle where that unique triangle has three acute angles. -

- Use the cases and diagrams in the proof of the Law of Sines (Theorem 8.15) to prove the area formulas given in Theorem 8.17. Why do those formulas yield square units when four quantities are being multiplied together?

Section 8.4 Exercise Answers can be found in the Appendix … Coming soon

- Recall that the word `Trigonometry' literally means `measuring triangles' so we are returning to our roots here. ↵

- Your Science teachers should thank us for this. ↵

- The exact value of

could be found using the difference identity for sine or a half-angle formula, but that becomes unnecessarily messy for the discussion at hand. Thus ``exact'' here means

could be found using the difference identity for sine or a half-angle formula, but that becomes unnecessarily messy for the discussion at hand. Thus ``exact'' here means  . ↵

. ↵ - To find an exact expression for

, we convert everything back to radians:

, we convert everything back to radians:  radians,

radians,  radians and

radians and  radians. Hence,

radians. Hence,  radians

radians  . ↵

. ↵ - An exact answer for

in this case is

in this case is  radians

radians  . ↵

. ↵ - If this sounds familiar, it should. From Geometry, we know there are four congruence conditions for triangles: Angle-Angle-Side (AAS), Angle-Side-Angle (ASA), Side-Angle-Side (SAS) and Side-Side-Side (SSS). If we are given information about a triangle that meets one of these four criteria, then we are guaranteed that exactly one triangle exists which satisfies said criteria. ↵

- Remember, we have already argued that a triangle exists in this case! ↵

- Do you see why

must lie to the right (East) of

must lie to the right (East) of  ? ↵

? ↵ - Or by Definition 7.2 again

↵

↵ - I have friends who live in Pacifica, CA and their road is actually this steep. It's not a nice road to drive. ↵

- The word `plumb' here means that the tree is perpendicular to the horizontal. ↵