4.2 Properties of Power Functions and Their Graphs

Definition 4.2

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be nonzero real numbers. A power function is either a constant function or a function of the form

be nonzero real numbers. A power function is either a constant function or a function of the form ![]() .

.

Definition 4.2 broadens our scope of functions to include non-integer exponents such as ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . Our primary aim in this section is to ascribe meaning to these quantities.

. Our primary aim in this section is to ascribe meaning to these quantities.

4.2.1 Rational Number Exponents

The road to real number exponents starts by defining rational number exponents.

Definition 4.3

Let ![]() be a rational number where in lowest terms

be a rational number where in lowest terms ![]() where

where ![]() is an integer and

is an integer and ![]() is a natural number.[1] If

is a natural number.[1] If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then

, then

![]()

whenever ![]() is defined.[2]

is defined.[2]

Moreover, per this definition, ![]() , so we may rewrite principal roots as exponents:

, so we may rewrite principal roots as exponents: ![]() and

and ![]() . This makes sense from an algebraic standpoint because per Theorem 4.2,

. This makes sense from an algebraic standpoint because per Theorem 4.2, ![]() . Hence if we were to assign an exponent notation to

. Hence if we were to assign an exponent notation to ![]() , say

, say ![]() , then

, then ![]() . If the properties of exponents are to hold, then, necessarily,

. If the properties of exponents are to hold, then, necessarily, ![]() , so

, so ![]() or

or ![]() . While this argument helps motivate the notation, as we shall see shortly, great care must be exercised in applying exponent properties in these cases. The long and short of this is that root functions as defined in Section 4.1 are all members of the `power functions’ family.

. While this argument helps motivate the notation, as we shall see shortly, great care must be exercised in applying exponent properties in these cases. The long and short of this is that root functions as defined in Section 4.1 are all members of the `power functions’ family.

Another important item worthy of note in Definition 4.3 is that it is absolutely essential we express the rational number ![]() in lowest terms before applying the root-power definition. For example, consider

in lowest terms before applying the root-power definition. For example, consider ![]() . Expressing

. Expressing ![]() in lowest terms, we get:

in lowest terms, we get: ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() or

or ![]() , either of which is defined for all real numbers

, either of which is defined for all real numbers ![]() . In contrast, consider the equivalence

. In contrast, consider the equivalence ![]() . Here, the expression

. Here, the expression ![]() is defined only for

is defined only for ![]() owing to the presence of the even indexed root,

owing to the presence of the even indexed root, ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() unless

unless ![]() . On the other hand, the expression

. On the other hand, the expression ![]() is defined for all numbers,

is defined for all numbers, ![]() , as

, as ![]() for all

for all ![]() . In fact, it can be shown that

. In fact, it can be shown that ![]() for all real numbers. This means

for all real numbers. This means ![]() . So, to review, in general we have:

. So, to review, in general we have: ![]() , but

, but ![]() unless

unless ![]() . Once again the easiest way to avoid confusion here is to reduce the exponent to lowest terms before converting it to root-power notation.

. Once again the easiest way to avoid confusion here is to reduce the exponent to lowest terms before converting it to root-power notation.

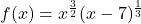

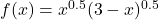

Likewise, we have to be careful about the properties of exponents when it comes to rational exponents. Consider, for instance, the product rule for integer exponents: ![]() . Consider

. Consider ![]() and

and ![]() . In the first case,

. In the first case, ![]() only for

only for ![]() . In the second case,

. In the second case, ![]() for all real numbers

for all real numbers ![]() . Even though

. Even though ![]() for

for ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are different functions as they have different domains.

are different functions as they have different domains.

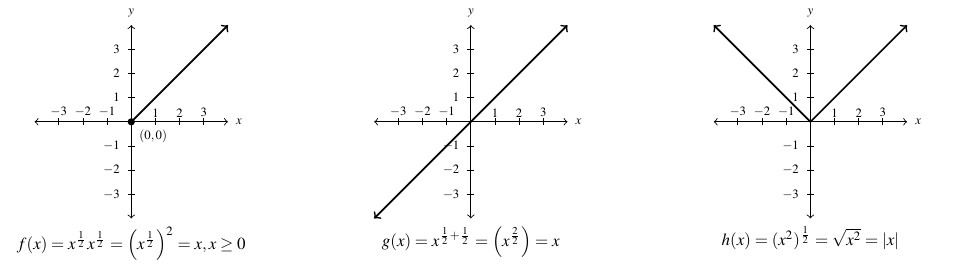

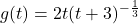

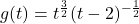

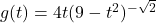

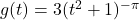

Similarly, the power rule for integer exponents: ![]() does not hold in general for rational exponents. To see this, consider the three functions:

does not hold in general for rational exponents. To see this, consider the three functions: ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . In the first case,

. In the first case, ![]() for

for ![]() only (this is the same function

only (this is the same function ![]() above.) In the second case, the rational number

above.) In the second case, the rational number ![]() , so

, so ![]() for all real numbers,

for all real numbers, ![]() (this is the same function

(this is the same function ![]() from above.) In the last case,

from above.) In the last case, ![]() for all real numbers,

for all real numbers, ![]() . Once again, despite

. Once again, despite ![]() for all

for all ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]() and

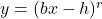

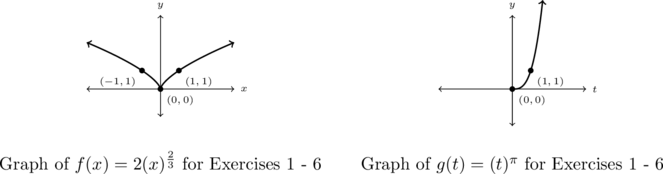

and ![]() and are three different functions. We graph

and are three different functions. We graph ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() below.

below.

In general, the properties of integer exponents do not extend to rational exponents unless the bases involved represent non-negative real numbers or the roots involved are odd. We have the following:

Theorem 4.3

Let ![]() and

and ![]() are rational numbers. The following properties hold provided none of the computations results in division by

are rational numbers. The following properties hold provided none of the computations results in division by ![]() and either

and either ![]() and

and ![]() have odd denominators or

have odd denominators or ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

- Product Rules:

and

and  .

. - Quotient Rules:

and

and

- Power Rule:

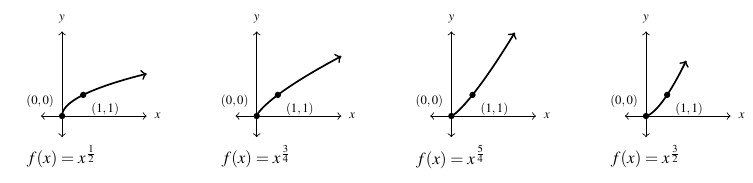

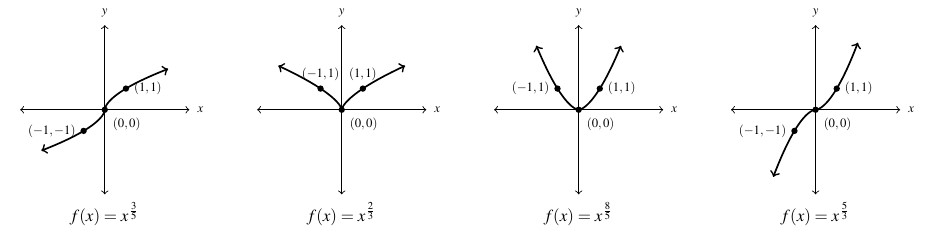

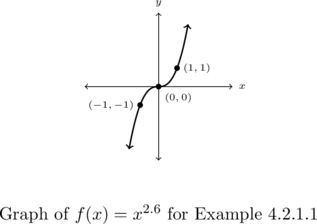

Next, we turn our attention to the graphs of ![]() for varying values of

for varying values of ![]() and

and ![]() . When

. When ![]() is even, the domain is restricted owing to the presence of the even indexed root to

is even, the domain is restricted owing to the presence of the even indexed root to ![]() . The range is likewise

. The range is likewise ![]() , a fact left to the reader. All of the functions below are increasing on their domains, and it turns out this is always the case provided

, a fact left to the reader. All of the functions below are increasing on their domains, and it turns out this is always the case provided ![]() . There is, however, a difference in how the functions are increasing – and this is the concept of concavity. As with many concepts we’ve encountered so far in the text, concavity is most precisely defined using Calculus terminology, but we can nevertheless get a sense of concavity geometrically. For us, a curve is concave up over an interval if it resembles a portion of a `

. There is, however, a difference in how the functions are increasing – and this is the concept of concavity. As with many concepts we’ve encountered so far in the text, concavity is most precisely defined using Calculus terminology, but we can nevertheless get a sense of concavity geometrically. For us, a curve is concave up over an interval if it resembles a portion of a `![]() ‘ shape. Similarly, a curve is called concave down over an interval if resembles part of a `

‘ shape. Similarly, a curve is called concave down over an interval if resembles part of a `![]() ‘ shape. When

‘ shape. When ![]() , the graphs of

, the graphs of ![]() resemble the left half of

resemble the left half of ![]() and so are concave down; when

and so are concave down; when ![]() , the graphs resemble the right half of a `

, the graphs resemble the right half of a `![]() ‘ and are hence described as `concave up.’

‘ and are hence described as `concave up.’

Below we graph several examples of ![]() where

where ![]() is odd. Here, the domain is

is odd. Here, the domain is ![]() because the index on the root here is odd. Note that when

because the index on the root here is odd. Note that when ![]() is even, the graphs appear to be symmetric about the

is even, the graphs appear to be symmetric about the ![]() -axis and the range looks to be

-axis and the range looks to be ![]() . When

. When ![]() is odd, the graphs appear to be symmetric about the origin with range

is odd, the graphs appear to be symmetric about the origin with range ![]() . We leave verification of these facts to the reader. Note here also that for

. We leave verification of these facts to the reader. Note here also that for ![]() , the graphs are down for

, the graphs are down for ![]() and concave up for

and concave up for ![]() .

.

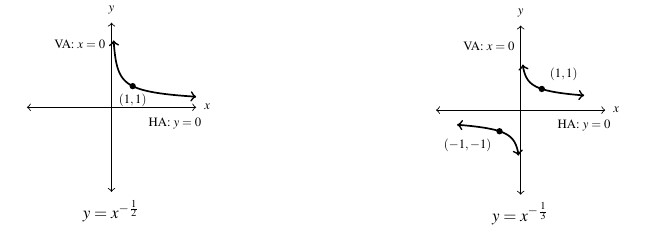

When ![]() , we have variables appear in the denominator which open the opportunities for vertical and horizontal asymptotes. Below are graphed two examples

, we have variables appear in the denominator which open the opportunities for vertical and horizontal asymptotes. Below are graphed two examples

Unsurprisingly, Theorem 4.1, which, as stated, applied to root functions, generalizes to all rational powers.

Theorem 4.4

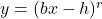

For real numbers ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() and rational number

and rational number ![]() with

with ![]() , the graph of

, the graph of ![]() can be obtained from the graph of

can be obtained from the graph of ![]() by performing the following operations, in sequence:

by performing the following operations, in sequence:

- add

to each of the

to each of the  -coordinates of the points on the graph of

-coordinates of the points on the graph of  . This results in a horizontal shift to the right if

. This results in a horizontal shift to the right if  or left if

or left if  .

.

NOTE: This transforms the graph of to

to  .

. - divide the

-coordinates of the points on the graph obtained in Step 1 by

-coordinates of the points on the graph obtained in Step 1 by  . This results in a horizontal scaling, but may also include a reflection about the

. This results in a horizontal scaling, but may also include a reflection about the  -axis if

-axis if  .

.

NOTE: This transforms the graph of to

to  .

. - multiply the

-coordinates of the points on the graph obtained in Step 2 by

-coordinates of the points on the graph obtained in Step 2 by  . This results in a vertical scaling, but may also include a reflection about the

. This results in a vertical scaling, but may also include a reflection about the  -axis if

-axis if  .

.

NOTE: This transforms the graph of to

to  .

. - add

to each of the

to each of the  -coordinates of the points on the graph obtained in Step 3. This results in a vertical shift up if

-coordinates of the points on the graph obtained in Step 3. This results in a vertical shift up if  or down if

or down if  .

.

NOTE: This transforms the graph of to

to  .

.

The proof of Theorem 4.4 is identical to that of Theorem 4.1, and we suggest the reader work through the details. We give Theorem 4.4 a test run in the following example.

Example 4.2.1

Example 4.2.1.1

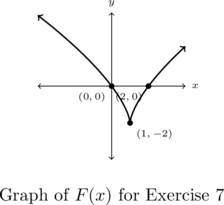

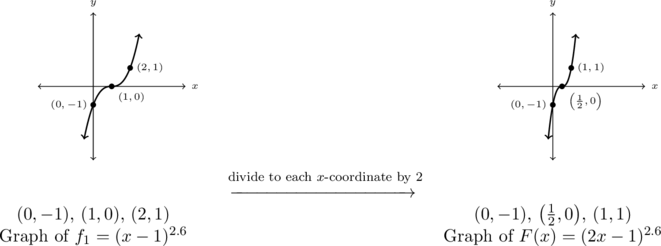

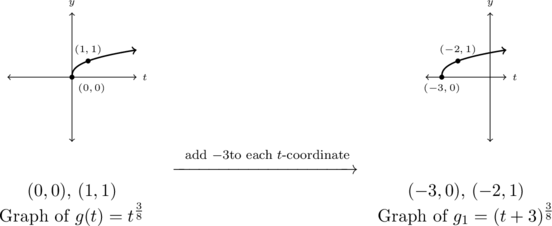

Use the given graphs of ![]() below long with Theorem 4.4 to graph

below long with Theorem 4.4 to graph ![]() . State the domain and range of

. State the domain and range of ![]() using interval notation.

using interval notation.

Graph ![]() .

.

Solution:

Graph ![]() using the graph of

using the graph of ![]() provided.

provided.

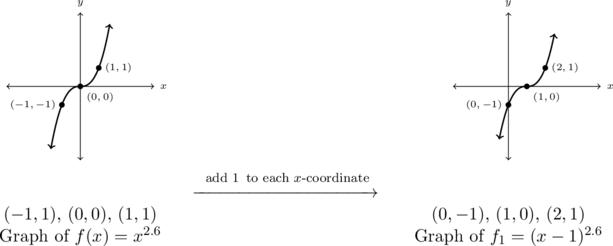

The expression ![]() is given to us in the form prescribed by Theorem 4.4, and we identify

is given to us in the form prescribed by Theorem 4.4, and we identify ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Even though the graph of ![]() is given to us, it’s worth taking a moment to reinforce some concepts. We proceed as we have several times in the past, beginning with the horizontal shift.

is given to us, it’s worth taking a moment to reinforce some concepts. We proceed as we have several times in the past, beginning with the horizontal shift.

Step 2: divide each of the ![]() -coordinates of each of the points on the graph of

-coordinates of each of the points on the graph of ![]() by

by ![]() :

:

In lowest terms, ![]() , thus it makes sense the domain and range of

, thus it makes sense the domain and range of ![]() are both all real numbers and the graph is symmetric about the origin.[4] Moreover, because

are both all real numbers and the graph is symmetric about the origin.[4] Moreover, because ![]() , the concavity matches what we would expect, too.

, the concavity matches what we would expect, too.

We get the domain and range here are both ![]() .

.

Example 4.2.1.2

Use the given graph of ![]() below long with Theorem 4.4 to graph

below long with Theorem 4.4 to graph ![]() . State the domain and range of

. State the domain and range of ![]() using interval notation.

using interval notation.

Graph ![]() .

.

Solution:

Graph ![]() using the graph of

using the graph of ![]() provided.

provided.

We first need to rewrite ![]() in the form required by Theorem 4.4:

in the form required by Theorem 4.4: ![]() . We identify

. We identify ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]()

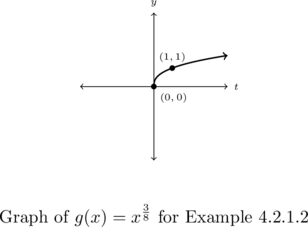

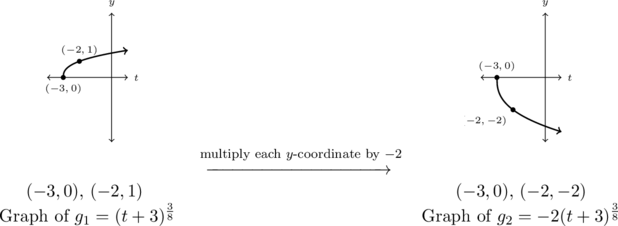

Step 1: add ![]() to each of the

to each of the ![]() -coordinates of each of the points on the graph of

-coordinates of each of the points on the graph of ![]() :

:

Step 2: ![]() , so we proceed directly to Step 3.

, so we proceed directly to Step 3.

Step 3: multiply each of the ![]() -coordinates of each of the points on the graph of

-coordinates of each of the points on the graph of ![]() by

by ![]() :

:

Step 4: add ![]() to each of the

to each of the ![]() -coordinates of each of the points on the graph of

-coordinates of each of the points on the graph of ![]() :

:

As ![]() is in lowest terms and has an even denominator,8, it makes sense the domain and range of

is in lowest terms and has an even denominator,8, it makes sense the domain and range of ![]() is

is ![]() . Also, because

. Also, because ![]() , the graph of

, the graph of ![]() is concave down, as we would expect.

is concave down, as we would expect.

From the graph, we get the domain is ![]() and the range is

and the range is ![]()

We now turn our attention to more complicated functions involving rational exponents.

Example 4.2.2

Example 4.2.2.1

For the following function: ![]()

- Analytically:

- State the domain

- Identify the axis intercepts

- Analyze the end behavior

- Construct a sign diagram for each function using the intercepts and sketch a graph

- Use technology to determine:

- The range

- The local extrema, if they exist

- Intervals where the function is increasing

- Intervals where the function is decreasing

Solution:

Analyze and graph ![]() .

.

We first note that, owing to the negative exponent, the quantity ![]() is in the denominator, alerting us to a potential domain issue. Rewriting

is in the denominator, alerting us to a potential domain issue. Rewriting ![]() we set about solving

we set about solving ![]() . Cubing both sides and extracting square roots gives

. Cubing both sides and extracting square roots gives ![]() or

or ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() is excluded from the domain.[5] The root involved here is odd (

is excluded from the domain.[5] The root involved here is odd (![]() ), so the only issue we have is with the denominator, hence our domain is

), so the only issue we have is with the denominator, hence our domain is ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

While not required to do so, we analyze the behavior of ![]() near

near ![]() . As

. As ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() . Hence,

. Hence,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} (x^3-8)^{\frac{2}{3}} &=& \sqrt[3]{(x^3-8)^2} \\ &\approx & \sqrt[3]{(\text{small } (-))^2} \\ & \approx & \sqrt[3]{\text{small } (+)} \\ &\approx & \text{small } (+) \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-89de6a32701efe946d764bf3bb76fa68_l3.png)

As such,

![]()

We conclude as ![]() ,

, ![]() . As

. As ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , and we likewise get

, and we likewise get ![]()

This analysis suggests ![]() is a vertical asymptote to the graph.

is a vertical asymptote to the graph.

To find the ![]() -intercepts, we set

-intercepts, we set ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

We get ![]() is our only

is our only ![]() – (and

– (and ![]() -)intercept.

-)intercept.

For end behavior, we note that in the denominator the ![]() term dominates the constant term, so as

term dominates the constant term, so as ![]() ,

,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} f(x) &=& 3x^2(x^3-8)^{-\frac{2}{3}} \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{3x^2}{(x^3-8)^{\frac{2}{3}}} \\[8pt] &\approx & \dfrac{3x^2}{ (x^3)^{ \frac{2}{3} } } \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{3x^2}{\sqrt[3]{(x^3)^2}} \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{3x^2}{\sqrt[3]{x^6}} \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{3x^2}{x^2} \\[8pt] &=& 3 \end{array}\]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-986dc25b4835d98148e66ff7e7348ff8_l3.png)

This suggests ![]() is a horizontal asymptote to the graph.

is a horizontal asymptote to the graph.

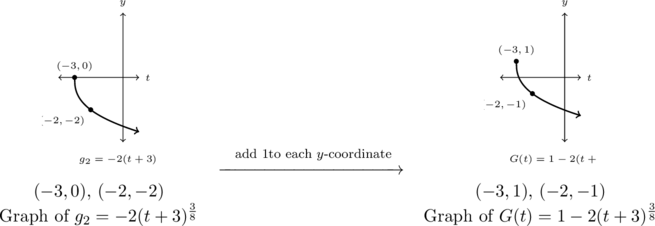

For the sign diagram, we note that ![]() has only one zero,

has only one zero, ![]() and is undefined at

and is undefined at ![]() . For all

. For all ![]() values between these two numbers,

values between these two numbers, ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

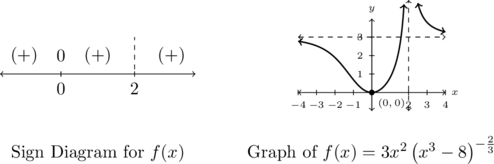

Our sign diagram for ![]() is below.

is below.

Graphing ![]() below bears out our analysis regarding zeros and asymptotes.

below bears out our analysis regarding zeros and asymptotes.

The range appears to be ![]() , with the graph of

, with the graph of ![]() crossing its horizontal asymptote between

crossing its horizontal asymptote between ![]() and

and ![]()

We see we have a single local minimum at ![]() with

with ![]() is decreasing on

is decreasing on ![]() and

and ![]() and increasing on

and increasing on ![]()

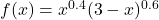

Example 4.2.2.2

For the following function: ![]()

- Analytically:

- State the domain

- Identify the axis intercepts

- Analyze the end behavior

- Construct a sign diagram for each function using the intercepts and sketch a graph

- Use technology to determine:

- The range

- The local extrema, if they exist

- Intervals where the function is increasing

- Intervals where the function is decreasing

Solution:

Analyze and graph ![]() .

.

To find the domain of ![]() , we have two issues to address: the denominator and an even (square) root. Solving

, we have two issues to address: the denominator and an even (square) root. Solving ![]() gives two excluded values,

gives two excluded values, ![]() .

.

For the numerator, we may rewrite ![]() , so we require

, so we require ![]() , or

, or ![]() . Extracting square roots, we have

. Extracting square roots, we have ![]() or

or ![]() which means

which means ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

Taking into account our excluded values ![]() , we get the domain of

, we get the domain of ![]() is

is ![]()

Looking near ![]() , we note that as

, we note that as ![]() ,

, ![]() , a positive number. As

, a positive number. As ![]() ,

,

![]()

, so

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} g(t) &\approx& \frac{32^{1.5}}{\text{small } (+) }\\[8pt] &\approx & \text{big } (+) \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-61307f9b25c62ba913b30ba460da0327_l3.png)

This suggests as ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

On the other hand, as ![]() ,

,

![]()

, so

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} g(t) &\approx & \frac{32^{1.5}}{\text{small } (-)}\\[8pt] &\approx & \text{big } (-) \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-1fe7dc5af8adbf27249ec96e57c4bc4b_l3.png)

, suggesting ![]() . Similarly, we find as

. Similarly, we find as ![]() ,

, ![]() and as

and as ![]() ,

, ![]()

This suggests we have two vertical asymptotes to the graph of ![]() :

: ![]() and

and ![]()

To find the ![]() -intercepts, we set

-intercepts, we set ![]() and solve

and solve ![]() . This reduces to

. This reduces to ![]() or

or ![]() . As these are (just barely!) in the domain of

. As these are (just barely!) in the domain of ![]() , we have two

, we have two ![]() -intercepts,

-intercepts, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The graph of ![]() has no

has no ![]() -intercepts, because

-intercepts, because ![]() is not in the domain of

is not in the domain of ![]() , so

, so ![]() is undefined.

is undefined.

Regarding end behavior, as ![]() , the

, the ![]() in both numerator and denominator dominate the constant terms, so we have

in both numerator and denominator dominate the constant terms, so we have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} g(t) &=& \dfrac{ (t^2-4)^{\frac{3}{2}} }{t^2-36} \\[8pt] &\approx & \dfrac{\left(t^2\right)^{\frac{3}{2}}}{t^2} \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{\left(\sqrt{t^2} \right)^3}{t^2} \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{|t|^3}{t^2} \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{|t| |t|^2}{t^2} \\[8pt] &=& \dfrac{|t| t^2}{t^2} \\[8pt] &=& |t| \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-29af3e6dfb91ebd4fb824bebc42c0f4e_l3.png)

This suggests that as ![]() , the graph of

, the graph of ![]() resembles

resembles ![]() . Using the piecewise definition of

. Using the piecewise definition of ![]() , we have that as

, we have that as ![]() ,

, ![]() and as

and as ![]() ,

, ![]() . In other words, the graph of

. In other words, the graph of ![]() has two slant asymptotes with slopes

has two slant asymptotes with slopes ![]()

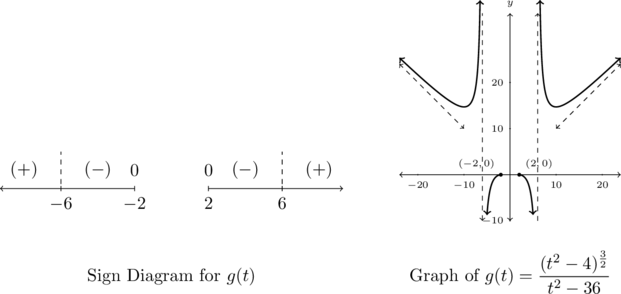

For the sign diagram for ![]() , we note that

, we note that ![]() has zeros

has zeros ![]() and is undefined at

and is undefined at ![]() . Moreover, there is a gap in the domain for all values in the interval

. Moreover, there is a gap in the domain for all values in the interval ![]() , so we excise that portion of the real number line for our discussion.

, so we excise that portion of the real number line for our discussion.

We find ![]() or

or ![]() on the intervals

on the intervals ![]() and

and ![]() while

while ![]() or

or ![]() on

on ![]() and

and ![]()

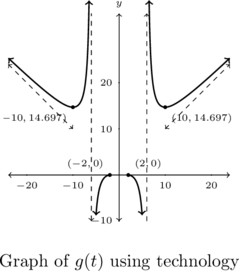

Our sign diagram for ![]() is below and graphing

is below and graphing ![]() below verifies our analysis.

below verifies our analysis.

From the graph, the range appears to be ![]() .

.

The points ![]() and

and ![]() are local minimums.

are local minimums. ![]() appears to be decreasing on

appears to be decreasing on ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . Likewise,

. Likewise, ![]() is increasing on

is increasing on ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The graph of ![]() certainly appears to be symmetric about the

certainly appears to be symmetric about the ![]() -axis.

-axis.

We leave it to the reader to show ![]() is, indeed, an even function.

is, indeed, an even function.

4.2.2 Real Number Exponents

We wish now to extend the concept of `exponent’ from rational to all real numbers which means we need to discuss how to interpret an irrational exponent. Once again, the notions presented here are best discussed using the language of Calculus or Analysis, but we nevertheless do what we can with the notions we have.

Consider the wildly famous irrational number ![]() . The number

. The number ![]() is defined geometrically as the ratio of the circumference of a circle to that circle’s diameter.[6] The reason we use the symbol `

is defined geometrically as the ratio of the circumference of a circle to that circle’s diameter.[6] The reason we use the symbol `![]() ‘ instead of any numerical expression is that

‘ instead of any numerical expression is that ![]() is an irrational number, and, as such, its decimal representation neither terminates nor repeats. Hence we approximate

is an irrational number, and, as such, its decimal representation neither terminates nor repeats. Hence we approximate ![]() as

as ![]() or

or ![]() . No matter how many digits we write, however, what we have is a rational number approximation of

. No matter how many digits we write, however, what we have is a rational number approximation of ![]() .

.

The good news is we can approximate ![]() to any desired accuracy using rational numbers by taking enough digits, so while we’ll never `reach’ the exact value of

to any desired accuracy using rational numbers by taking enough digits, so while we’ll never `reach’ the exact value of ![]() with rational numbers, we can get as close as we like to

with rational numbers, we can get as close as we like to ![]() using rational numbers. That being said, we assume

using rational numbers. That being said, we assume ![]() exists on the real number line, despite the fact the list of digits to pinpoint its location is, in some sense, infinite.

exists on the real number line, despite the fact the list of digits to pinpoint its location is, in some sense, infinite.

We take this approach when defining the value of a number raised to an irrational exponent. Consider, for instance, ![]() . We can compute

. We can compute

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{rcl} 2^3 &=& 8 \\ [6pt] 2^{3.1} &=& 2^{\frac{31}{10}} = \sqrt[10]{2^{31}} \approx 8.574\\[6pt] 2^{3.14} &=& 2^{\frac{314}{100}} = 2^{\frac{157}{50}} = \sqrt[50]{2^{157}} \approx 8.8512 \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-dabe11209700d92e1d688f5256ef43a1_l3.png)

and so on, so one way to define ![]() as the unique real number we obtain as the exponents `approach’

as the unique real number we obtain as the exponents `approach’ ![]() .

.

It is with this understanding that we present the notion of a `power function,’ as described in Definition 4.2: ![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() are nonzero real number parameters. Here the exponent

are nonzero real number parameters. Here the exponent ![]() is open to any (nonzero) real number. Because of how we define real number exponents, if

is open to any (nonzero) real number. Because of how we define real number exponents, if ![]() is irrational, then

is irrational, then ![]() to avoid having negatives under even-indexed roots as we go through the approximation process.[7]

to avoid having negatives under even-indexed roots as we go through the approximation process.[7]

In general, real number exponents inherit their properties from rational number exponents. For instance, Theorem 4.3 also holds for all real number exponents and the graphs of power functions inherit their behavior from graphs of rational exponent functions. More specifically, the graphs of functions of the form ![]() where

where ![]() all contain the points

all contain the points ![]() and

and ![]() . Moreover, these functions are increasing and their graphs are concave down if

. Moreover, these functions are increasing and their graphs are concave down if ![]() and concave up if

and concave up if ![]() .

.

Theorem 4.4 generalizes to real number power functions, so, for instance to graph ![]() , one need only start with

, one need only start with ![]() and shift horizontally two units to the right. (See the Exercises.)

and shift horizontally two units to the right. (See the Exercises.)

4.2.3 Section Exercises

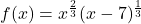

In Exercises 1 – 6, use the given graphs along with Theorem 4.4 to graph the given function. Track at least two points and state the domain and range using interval notation.

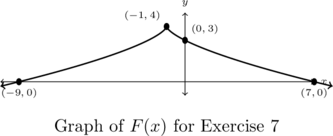

In Exercises 7 – 8, find a formula for each function below in the form ![]() . NOTE: There may be more than one solution!

. NOTE: There may be more than one solution!

For each function in Exercises 9 – 16 below

- Analytically:

- state the domain

- identify the axis intercepts

- analyze the end behavior

- Construct a sign diagram for each function using the intercepts and sketch a graph

- Use technology to determine

- the range

- the local extrema, if they exist

- intervals where the function is increasing/decreasing

- any `unusual steepness’ or `local’ verticality

- vertical asymptotes

- horizontal / slant asymptotes

- Comment on any observed symmetry

- For each function

listed below, compute the average rate of change over the indicated interval.[8] What trends do you observe? How do your answers manifest themselves graphically? Compare the results of this exercise with those of Exercise 51 in Section 2.2 and Exercise 43 in Section 3.2.

listed below, compute the average rate of change over the indicated interval.[8] What trends do you observe? How do your answers manifest themselves graphically? Compare the results of this exercise with those of Exercise 51 in Section 2.2 and Exercise 43 in Section 3.2.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \begin{array}{|r||c|c|c|c|} \hline f(x) & [0.9, 1.1] & [0.99, 1.01] &[0.999, 1.001] & [0.9999, 1.0001] \\ \hline x^{\frac{1}{2}} &&&& \\ \hline x^{\frac{2}{3}} &&&& \\ \hline x^{-0.23} &&&& \\ \hline x^{\pi} &&&& \\ \hline \end{array} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-401383ff2736d5478ff3845546c34320_l3.png)

- The National Weather Service uses the following formula to calculate the wind chill:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ W = 35.74 + 0.6215 \, T_{a} - 35.75\, V^{0.16} + 0.4275 \, T_{a} \, V^{0.16} \]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-774ccfafed06fc7614ebfc21b8d1769e_l3.png)

where

is the wind chill temperature in

is the wind chill temperature in  F,

F,  is the air temperature in

is the air temperature in  F, and

F, and  is the wind speed in miles per hour. Note that

is the wind speed in miles per hour. Note that  is defined only for air temperatures at or lower than

is defined only for air temperatures at or lower than  F and wind speeds above

F and wind speeds above  miles per hour.

miles per hour.- Suppose the air temperature is

and the wind speed is

and the wind speed is  miles per hour. Compute the wind chill temperature. Round your answer to two decimal places.

miles per hour. Compute the wind chill temperature. Round your answer to two decimal places. - Suppose the air temperature is

F and the wind chill temperature is

F and the wind chill temperature is  F. Compute the wind speed. Round your answer to two decimal places.

F. Compute the wind speed. Round your answer to two decimal places.

- Suppose the air temperature is

Section 4.2 Exercise Answers can be found in the Appendix … Coming soon

- Recall `lowest terms' means

and

and  have no common factors other than

have no common factors other than  . ↵

. ↵ - That is, if

is even,

is even,  and if

and if  ,

,  . ↵

. ↵ - Either

is a special case in Definition 4.3 or we need to define what is meant by

is a special case in Definition 4.3 or we need to define what is meant by ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \sqrt[1]{x}](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-6e836611e8b914ebffe907967683b3db_l3.png) . The authors chose the former. ↵

. The authors chose the former. ↵ - The domain is all real numbers as the denominator (root)

is odd; the range is all real numbers because the numerator (power)

is odd; the range is all real numbers because the numerator (power)  is odd. Because both power and root are odd, the function itself is an odd function, hence the symmetry about the origin. ↵

is odd. Because both power and root are odd, the function itself is an odd function, hence the symmetry about the origin. ↵ - In general if

where

where  , then

, then  . ↵

. ↵ - This works for each and every circle, by the way, regardless of how large or small the circle is! ↵

- or

if

if  is negative. ↵

is negative. ↵ - See Definition 1.11 in Section 1.3.4 for a review of this concept, as needed. ↵

A power function is a function of the form constant times x to a real number power.