VII. Researched Writing

7.4 Developing a Research Strategy

Deborah Bernnard; Greg Bobish; Jenna Hecker; Irina Holden; Allison Hosier; Trudi Jacobson; Tor Loney; Daryl Bullis; and Sarah LeMire

Sarah’s art history professor just assigned the course project and Sarah is delighted that it isn’t the typical research paper. Rather, it involves putting together a website to help readers understand a topic. It will certainly help Sarah get a grasp on the topic herself. Learning by attempting to teach others, she agrees, might be a good idea. The professor wants the website to be written for people who are interested in the topic and with backgrounds similar to the students in the course. Sarah likes that a target audience is defined, and since she has a good idea of what her friends might understand and what they would need more help with, she thinks it will be easier to know what to include in her site…well, at least easier than writing a paper for an expert like her professor.

An interesting feature of this course is that the professor has formed the students into teams. Sarah wasn’t sure she liked this idea at the beginning, but it seems to be working out okay. Sarah’s team has decided that their topic for this website will be 19th century women painters. Her teammate Chris seems concerned: “Isn’t that an awfully big topic?” The team checks with the professor who agrees they would be taking on far more than they could successfully explain on their website. He suggests they develop a draft thesis statement to help them focus, and after several false starts, they come up with:

The involvement of women painters in the Impressionist movement had an effect upon the subjects portrayed.

They decide this sounds more manageable. Because Sarah doesn’t feel comfortable on the technical aspects of setting up the website, she offers to start locating resources that will help them to develop the site’s content. The next time the class meets, Sarah tells her teammates what she has done so far:

“I thought I’d start with some scholarly sources, since they should be helpful, right? I put a search into the online catalog for the library, but nothing came up! The library should have books on this topic, shouldn’t it? I typed the search in exactly as we have it in our thesis statement. That was so frustrating. Since that didn’t work, I tried Google, and put in the search. I got over 8 million results, but when I looked over the ones on the first page, they didn’t seem very useful. One was about the feminist art movement in the 1960s, not during the Impressionist period. The results all seemed to have the words I typed highlighted, but most really weren’t useful. I am sorry I don’t have much to show you. Do you think we should change our topic?”

Alisha suggests that Sarah talk with a reference librarian. She mentions that a librarian came to talk to one of her other classes about doing research, and it was really helpful. Alisha thinks that maybe Sarah shouldn’t have entered the entire thesis statement as the search, and maybe she should have tried databases to find articles. The team decides to brainstorm all the search tools and resources they can think of.

Here’s what they came up with:

Brainstormed List of Search Tools and Resources

|

Search Tools and Resources |

|---|

|

Wikipedia |

|

Professor |

|

Google search |

|

JSTOR database |

Based on your experience, do you see anything you would add?

Sarah and her team think that their list is pretty good. They decide to take it further and list the advantages and limitations of each search tool, at least as far as they can determine.

Brainstormed Advantages and Disadvantages of Search Tools and Resources

|

Search Tools and Resources |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Search Tool |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

Wikipedia |

Easy access, list of references |

Professors don’t seem to like it, possibly misinformation |

|

Professor |

The expert! |

Not sure we can get to office hours; we want to appear self-directed |

|

Google search |

Lots of results |

We need a better search term |

|

JSTOR database |

Authoritative, scholarly articles |

None that we know of |

Alisha suggests that Sarah should show the worksheet to a librarian and volunteers to go with her. The librarian, Mr. Harrison, says they have made a really good start, but he can fill them in on some other search strategies that will help them to focus on their topic. He asks if Sarah and Alisha would like to learn more.

Let’s step back from this case study and think about the elements that someone doing research should plan before starting to enter search terms in Google, Wikipedia, or even a scholarly database. There is some preparation you can do to make things go much more smoothly than they have for Sarah.

Self-Reflection

As you work through your own research quests, it is very important to be self-reflective. Consider:

- What do you really need to find?

- Do you need to learn more about the general subject before you can identify the focus of your search?

- How thoroughly did you develop your search strategy?

- Did you spend enough time finding the best tools to search?

- What is going really well, so well that you’ll want to remember to do it in the future?

Another term for what you are doing is metacognition, or thinking about your thinking. Reflect on what Sarah is going through. Does some of it sound familiar based on your own experiences? You may already know some of the strategies presented here. Do you do them the same way? How does it work? What pieces are new to you? When might you follow this advice? Don’t just let the words flow over you; rather, think carefully about the explanation of the process. You may disagree with some of what you read. If you do, follow through and test both methods to see which provides better results.

Selecting Search Tools

After you have thought the planning process through more thoroughly, think about the best place to find information for your topic and for the type of paper. Part of planning to do research is determining which search tools will be the best ones to use. This applies whether you are doing scholarly research or trying to answer a question in your everyday life, such as what would be the best place to go on vacation. “Search tools” might be a bit misleading since a person might be the source of the information you need. Or it might be a web search engine, a specialized database, an association—the possibilities are endless. Often people automatically search Google first, regardless of what they are looking for. Choosing the wrong search tool may just waste your time and provide only mediocre information, whereas other sources might provide really spot-on information and quickly, too. In some cases, a carefully constructed search on Google, particularly using the advanced search option, will provide the necessary information, but other times it won’t. This is true of all sources: make an informed choice about which ones to use for a specific need.

So, how do you identify search tools? Let’s begin with a first-rate method. For academic research, talking with a librarian or your professor is a great start. They will direct you to those specialized tools that will provide access to what you need. If you ask a librarian for help, they may also show you some tips about searching in the resources. This section will cover some of the generic strategies that will work in many search tools, but a librarian can show you very specific ways to focus your search and retrieve the most useful items.

If neither your professor nor a librarian is available when you need help, take a look at the TAMU Libraries website. There is a Help button in the top right corner of the website that will direct you to assistance via phone, chat, text, and email. Under the Guides button, you’ll find class- and subject-related guides that list useful databases and other resources for particular classes and majors to assist researchers. There is also a directory of the databases the library subscribes to and the subjects they cover. Take advantage of the expertise of librarians by using such guides. Novice researchers usually don’t think of looking for this type of help and, as a consequence, often waste time.

When you are looking for non-academic material, consider who cares about this type of information. Who works with it? Who produces it or the help guides for it? Some sources are really obvious and you are already using them—for example, if you need information about the weather in London three days from now, you might check Weather.com for London’s forecast. You don’t go to a library (in person or online), and you don’t do a research database search. For other information you need, think the same way. Are you looking for anecdotal information on old railroads? Find out if there is an organization of railroad buffs. You can search on the web for this kind of information or, if you know about and have access to it, you could check the Encyclopedia of Associations. This source provides entries for all U.S. membership organizations which can quickly lead you to a potentially wonderful source of information. Librarians can point you to tools like these.

Consider Asking an Expert

Have you thought about using people, not just inanimate sources, as a way to obtain information? This might be particularly appropriate if you are working on an emerging topic or a topic with local connections. There are a variety of reasons that talking with someone will add to your research.

For personal interactions, there are other specific things you can do to obtain better results. Do some background work on the topic before contacting the person you hope to interview. The more familiarity you have with your topic and its terminology, the easier it will be to ask focused questions. Focused questions are important if you want to get into the meat of what you need. Asking general questions because you think the specifics might be too detailed rarely leads to the best information. Acknowledge the time and effort someone is taking to answer your questions, but also realize that people who are passionate about subjects enjoy sharing what they know. Take the opportunity to ask experts about sources they would recommend. One good place to start is with the librarians at the Texas A&M University Libraries. Visit the library information page for details on how to contact a librarian.[1]

Determining Search Concepts and Keywords

Once you’ve selected some good resources for your topic, and possibly talked with an expert, it is time to move on to identify words you will use to search for information on your topic in various databases and search engines. This is sometimes referred to as building a search query. When deciding what terms to use in a search, break down your topic into its main concepts. Don’t enter an entire sentence or a full question. Different databases and search engines process such queries in different ways, but many look for the entire phrase you enter as a complete unit rather than the component words. While some will focus on just the important words, such as Sarah’s Google search that you read about earlier in this chapter, the results are often still unsatisfactory. The best thing to do is to use the key concepts involved with your topic. In addition, think of synonyms or related terms for each concept. If you do this, you will have more flexibility when searching in case your first search term doesn’t produce any or enough results. This may sound strange since, if you are looking for information using a Web search engine, you almost always get too many results. Databases, however, contain fewer items, and having alternative search terms may lead you to useful sources. Even in a search engine like Google, having terms you can combine thoughtfully will yield better results.

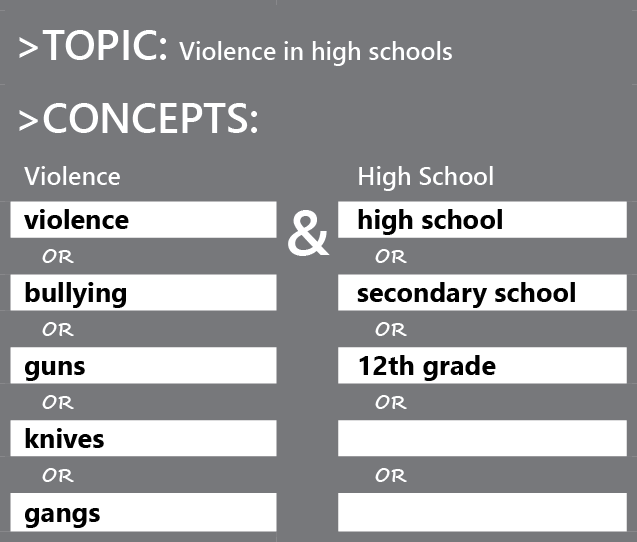

The worksheet in Figure 7.4.1[2] is an example of a process you can use to come up with search terms. It illustrates how you might think about the topic of violence in high schools. Notice that this exact phrase is not what will be used for the search. Rather, it is a starting point for identifying the terms that will eventually be used.

Example Search Term Brainstorming Worksheet

Exercises

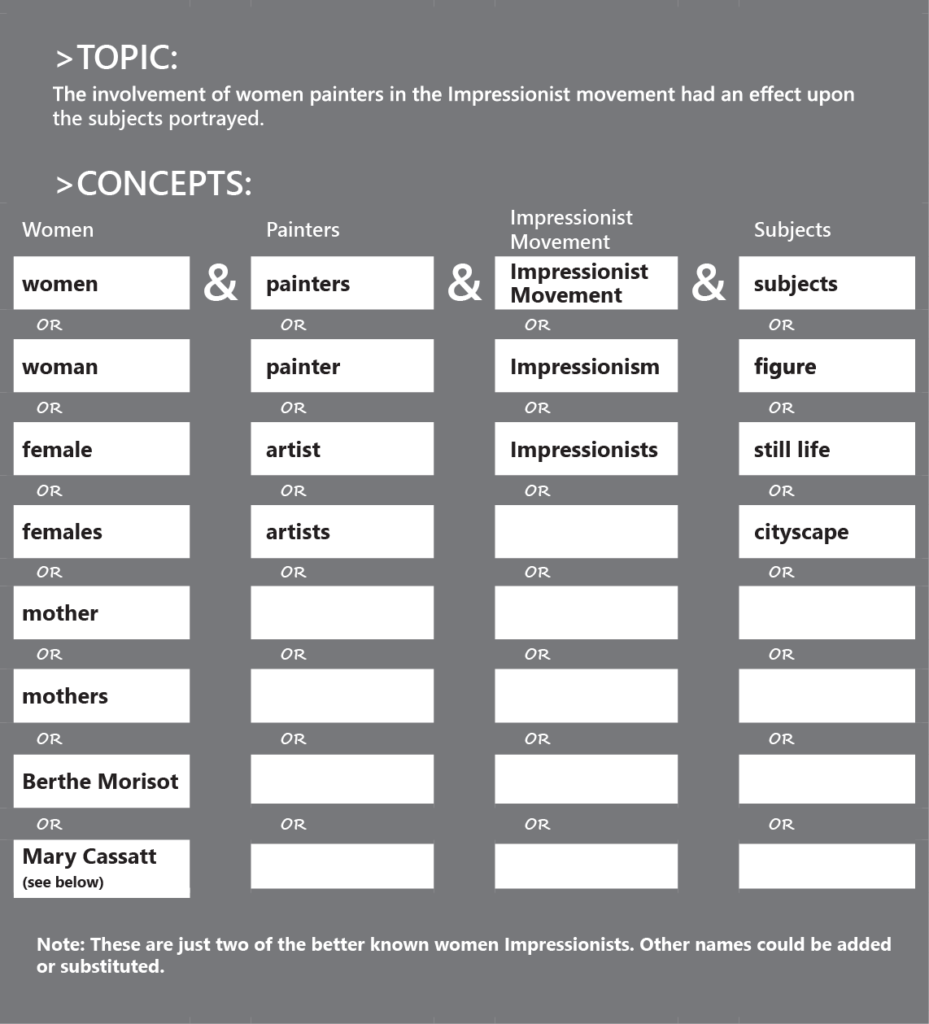

Now, use a clean copy of the same worksheet (Figure 7.4.2)[3] to think about the topic Sarah’s team is working on. How might you divide their topic into concepts and then search terms? Keep in mind that the number of concepts will depend on what you are searching for and that the search terms may be synonyms or narrower terms. Occasionally, you may be searching for something very specific, and in those cases, you may need to use broader terms as well. Jot down your ideas, then compare what you have written to the information on the second, completed worksheet (Figure 7.4.3)[4] and identify three differences.

Boolean Operators

Once you have the concepts you want to search, you need to think about how you will enter them into the search box. Often, but not always, Boolean operators will help you. You may be familiar with Boolean operators as they provide a way to link terms. There are three Boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT. (Note: Some databases require Boolean operators to be in all caps while others will accept the terms in either upper or lower case.

AND

We will start by capturing the ideas of the women creating the art. We will use women painters and women artists as the first step in our sample search. You could do two separate searches by typing one or the other of the terms into the search box of whatever tool you are using:

women painters women artists

You would end up with two separate results lists and have the added headache of trying to identify unique items from the lists. You could also search on the phrase:

women painters AND women artists

But once you understand Boolean operators, that last strategy won’t make as much sense as it seems to. The first Boolean operator is AND. AND is used to get the intersection of all the terms you wish to include in your search. With this example,

women painters AND women artists

you are asking that the items you retrieve have both of those terms. If an item only has one term, it won’t show up in the results. This is not what the searcher had in mind—she is interested in both artists and painters because she doesn’t know which term might be used. She doesn’t intend that both terms have to be used. Let’s go on to the next Boolean operator, which will help us out with this problem.

OR

OR is used when you want at least one of the terms to show up in the search results. If both do, that’s fine, but it isn’t a condition of the search. So OR makes a lot more sense for this search:

women painters OR women artists

Now, if you want to get fancy with this search, you could use both AND as well as OR:

women AND (painters OR artists)

The parentheses mean that these two concepts, painters and artists, should be searched as a unit, and the search results should include all items that use one word or the other. The results will then be limited to those items that contain the word women. If you decide to use parentheses for appropriate searches, make sure that the items contained within them are related in some way. With OR, as in our example, it means either of the terms will work. With AND, it means that both terms will appear in the document.

Exercise

Type both of the searches above in Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) and compare the results.

- Were they the same?

- If not, can you determine what happened?

- Which results list looked better?

Here is another example of a search string using both parentheses and two Boolean operators:

entrepreneurship AND (adolescents OR teens)

In this search, you are looking for entrepreneurial initiatives connected with people in their teens. Because there are so many ways to categorize this age group, it makes sense to indicate that either of these terms should appear in the results along with entrepreneurship.

Exercise

The search string above isn’t perfect. Can you pick out two problems with the search terms?

NOT

The third Boolean operator, NOT, can be problematic. NOT is used to exclude items from your search. If you have decided, based on the scope of the results you are getting, to focus only on a specific aspect of a topic, use NOT, but be aware that items are being lost in this search.

For example, if you entered

entrepreneurship AND (adolescents OR teens) NOT adults

you might lose some good results.

Exercise

Why might you lose some good results using the search above?

Other Helpful Search Techniques

Using Boolean operators isn’t the only way you can create more useful searches. In this section, we will review several others.

Truncation

In this search:

entrepreneurs AND (adolescents OR teens)

you might think that the items that are retrieved from the search can refer to entrepreneurs and to terms from the same root, like entrepreneurship. But because computers are very literal, they usually look for the exact terms you enter. While some search engines like Google are moving beyond this model, library databases tend to require more precision. Truncation, or searching on the root of a word and whatever follows, is how you can tell the database to do this type of search.

So, if you search on:

entrepreneur* AND (adolescents OR teens)

You will get items that refer to entrepreneur, but also entrepreneurship.

Look at these examples:

adolescen* educat*

Think of two or three words you might retrieve when searching on these roots. It is important to consider the results you might get and alter the root if need be. An example of this is polic*. Would it be a good idea to use this root if you wanted to search on policy or policies? Why or why not?

In some cases, a symbol other than an asterisk is used. To determine what symbol to use, check the help section in whatever resource you are using. The topic should show up under the truncation or stemming headings.

Phrase Searches

Phrase searches are particularly useful when searching the web. If you put the exact phrase you want to search in quotation marks, you will only get items with those words as a phrase and not items where the words appear separately in a document, website, or other resource. Your results will usually be fewer, although surprisingly, this is not always the case.

Exercise

Try these two searches in the search engine of your choice:

- essay exam

- “essay exam”

Was there a difference in the quality and quantity of results?

If you would like to find out if the database or search engine you are using allows phrase searching and the conventions for doing so, search the help section. These help tools can be very, well, helpful!

Advanced Searches

Advanced searching allows you to refine your search query and prompts you for ways to do this. Consider the basic Google search box. It is very minimalistic, but that minimalism is deceptive. It gives the impression that searching is easy and encourages you to just enter your topic without much thought to get results. You certainly do get many results, but are they really good results? Simple search boxes do many searchers a disfavor. There is a better way to enter searches.

Advanced search screens show you many of the options available to you to refine your search and, therefore, get more manageable numbers of better items. Many web search engines include advanced search screens, as do databases for searching research materials. Advanced search screens will vary from resource to resource and from web search engine to research database, but they often let you search using:

- Implied Boolean operators (for example, the “all the words” option is the same as using the Boolean AND);

- Limiters for date, domain (.edu, for example), type of resource (articles, book reviews, patents);

- Field (a field is a standard element, such as title of publication or author’s name);

- Phrase (rather than entering quote marks) Let’s see how this works in practice.

Practical Application: Google Searches

Go to the advanced search option in Google. You can find it at http://www.google.com/advanced_search

Take a look at the options Google provides to refine your search. Compare this to the basic Google search box. One of the best ways you can become a better searcher for information is to use the power of advanced searches, either by using these more complex search screens or by remembering to use Boolean operators, phrase searches, truncation, and other options available to you in most search engines and databases.

While many of the text boxes at the top of the Google Advanced Search page mirror concepts already covered in this section (for example, “this exact word or phrase” allows you to omit the quotes in a phrase search), the options for narrowing your results can be powerful. You can limit your search to a particular domain (such as .edu for items from educational institutions) or you can search for items you can reuse legally (with attribution, of course!) by making use of the “usage rights” option. However, be careful with some of the options as they may excessively limit your results. If you aren’t certain about a particular option, try your search with and without using it and compare the results. If you use a search engine other than Google, check to see if it offers an advanced search option: many do.

Subject Headings

In the section on advanced searches, you read about field searching. To explain further, if you know that the last name of the author whose work you are seeking is Wood, and that he worked on forestry-related topics, you can do a far better search using the author field. Just think what you would get in the way of results if you entered a basic search such as forestry AND wood. It is great to use the appropriate Boolean operator, but oh, the results you will get! But what if you specified that wood had to show up as part of the author’s name? This would limit your results quite a bit.

So what about forestry? Is there a way to handle that using a field search? The answer is yes. Subject headings are terms that are assigned to items to group them. An example is cars—you could also call them autos, automobiles, or even more specific labels like SUVs or vans. You might use the Boolean operator OR and string these all together. But if you found out that the sources you are searching use automobiles as the subject heading, you wouldn’t have to worry about all these related terms, and could confidently use their subject heading and get all the results, even if the author of the piece uses cars and not automobiles.

How does this work? In many databases, a person called an indexer or cataloger scrutinizes and enters each item. This person performs helpful, behind-the-scenes tasks such as assigning subject headings, age levels, or other indicators that make it easier to search very precisely. An analogy is tagging, although indexing is more structured than tagging. If you have tagged items online, you know that you can use any terms you like and that they may be very different from someone else’s tags. With indexing, the indexer chooses from a set group of terms. Obviously, this precise indexing isn’t available for web search engines—it would be impossible to index everything on the web. But if you are searching in a database, make sure you use these features to make your searches more precise and your results lists more relevant. You also will definitely save time.

You may be thinking that this sounds good. Saving time when doing research is a great idea. But how will you know what subject headings exist so you can use them? Here is a trick that librarians use. Even librarians don’t know what terms are used in all the databases or online catalogs that they use, so a librarian’s starting point isn’t very far from yours. But they do know to use whatever features a database provides to do an effective search. They find out about them by acting like a detective.

You’ve already thought about the possible search terms for your information needs. Enter the best search strategy you developed which might use Boolean operators or truncation. Scan the results to see if they seem to be on topic. If they aren’t, figure out what results you are getting that just aren’t right and revise your search. Terms you have searched on often show up in bold face type so they are easy to pick out. Besides checking the titles of the results, read the abstracts (or summaries), if there are any. You may get some ideas for other terms to use. But if your results are fairly good, scan them with the intent to find one or two items that seem to be precisely what you need. Get to the full record (or entry), where you can see all the details entered by the indexers. Figure 7.4.4[5] is an example from the Texas A&M University Libraries’ Quick Search, but keep in mind that the catalog or database you are using may have entries that look very different.

Once you have the “full” record (which does not refer to the full text of the item, but rather the full descriptive details about the book, including author, subjects, date, and place of publication, and so on), look at the subject headings and see what words are used. They may be called descriptors or some other term, but they should be recognizable as subjects. They may be identical to the terms you entered but if not, revise your search using the subject heading words. The result list should now contain items that are relevant for your needs.

It is tempting to think that once you have gone through all the processes around the circle, as seen in the diagram in Figure 7.4.5[6], your information search is done and you can start writing. However, research is a recursive process. You don’t start at the beginning and continue straight through until you end at the end. Once you have followed this planning model, you will often find that you need to alter or refine your topic and start the process again, as seen here:

![Circle divided into four with a box at each corner. Circle part 1: Refine topic [Box: Narrow or broaden scope, Select new aspect of topic] Circle part 2: Concepts [Box: Revise existing concepts, Add or eliminate concepts] Circle part 3: Determine relationships [Box: Boolean operators, Phrase searching] Circle part 4: Variations and refinements [Box: Truncations, field searching, subject headings]](https://pressbooks.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/sites/3/2022/05/image4-1.png)

This revision process may happen at any time before or during the preparation of your paper or other final product. The researchers who are most successful do this, so don’t ignore opportunities to revise.

So let’s return to Sarah and her search for information to help her team’s project. Sarah realized she needed to make a number of changes in the search strategy she was using. She had several insights that definitely led her to some good sources of information for this particular research topic. Can you identify the good ideas she implemented?

This section contains material from:

Bernnard, Deborah, Greg Bobish, Jenna Hecker, Irina Holden, Allison Hosier, Trudi Jacobson, Tor Loney, and Daryl Bullis. The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson. Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014. http://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711202425/https://milneopentextbooks.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/

- https://library.tamu.edu ↵

- “Concept Brainstorming,” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “Blank Concept Brainstorming Worksheet,” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “Completed Concept Brainstorming Worksheet” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “Full Record Entry for a Book” is a reproduction from July 2019 of a Texas A&M University Libraries catalog entry from the Texas A&M University Libraries Quick Search. https://library.tamu.edu. ↵

- “Planning Model” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

A statement, usually one sentence, that summarizes an argument that will later be explained, expanded upon, and developed in a longer essay or research paper. In undergraduate writing, a thesis statement is often found in the introductory paragraph of an essay. The plural of thesis is theses.

When something is described as scholarly, that means that has been written by and for the academic community. The term scholarly is commonly used as shorthand to indicate that information that has been peer reviewed or examined by other experts of the same academic field or discipline. Sometimes, the terms academic, scholarly, and peer reviewed are confused as synonyms; peer reviewed is a narrower term referring to an item that has been reviewed by experts in the field prior to publication, while academic is a broader term that also includes works that are written by and for academics, but that have not been peer reviewed.

A library catalog is a database of records for the items a library holds and/or to which it has access. Searching a library catalog is not the same as searching the web, even though you may see a similar search box for both tools. Library catalog searches can return information that you would not find on the open web, and the searching process will likely take longer to refine.

A librarian who specializes in helping the public find information. In academic librarians, reference librarians often have subject specialties.

A database is an organized collection of data in a digital format. Library research databases are often composed of academic publications like journal articles and book chapters, although there are also specialty databases that have data like engineering specifications or world news articles.

An online software tool used to find information on the web. Many popular online search engines return query results by using algorithms to return probable desired information.

A short account or telling of an incident or story, either personal or historical; anecdotal evidence is frequently found in the form of a personal experience rather than objective data or widespread occurrence.

Query: to ask a question or make an inquiry, often with some amount of skepticism involved.

With relation to a database, a query is a call for results. Most times a query is a search term entered into a search box.

A full record for a library item is all of the bibliographic information entered into the catalog for that particular work. Common entries in a full record will include the name of the work, the author, the publisher, the place of publication, the number of pages, the format, subject terms, and sometimes chapter titles.

A form of returning back to or reoccurrence, usually as a procedure or practice that can be repeated.