II. Getting Started

2.5 Prewriting

Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; and Terri Pantuso

Loosely defined, prewriting includes all the writing strategies employed before writing your first draft. Although many more prewriting strategies exist, the following section covers using experience and observations, reading, freewriting, asking questions, listing, and clustering/idea mapping. Using the strategies in the following section can help you overcome the fear of the blank page and confidently begin the writing process.

Choosing a Topic

In addition to understanding that writing is a process, writers also understand that choosing a good general topic for an assignment is an essential first step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A good topic not only covers what an assignment will be about, but it also fits the assignment’s purpose and its audience.

In the next few sections, you will follow a writer named Mariah as she explores and develops her essay’s topic and focus. You will also be planning one of your own. The first important step is for you to tell yourself why you are writing (to inform, to explain, or some other purpose) and for whom you are writing. Write your purpose and your audience on your own sheet of paper, and keep the paper close by as you read and write the first draft.

Experience and Observations

When selecting a topic, you may want to consider something that interests you or something based on your own life and personal experiences. Even everyday observations can lead to interesting topics. After writers think about their experiences and observations, they often take notes on paper to better develop their thoughts. These notes help writers discover what they have to say about their topic.

Reading

Reading plays a vital role in all the stages of the writing process, but it first figures in the development of ideas and topics. Different kinds of documents can help you choose and develop a topic. For example, a magazine cover advertising the latest research on the threat of global warming may catch your eye in the supermarket. This subject may interest you, and you may consider global warming as a topic. Or maybe a novel’s courtroom drama sparks your curiosity of a particular lawsuit or legal controversy.

After you choose a topic, critical reading is essential to the development of a topic. While reading almost any document, you evaluate the author’s point of view by thinking about his main idea and his support. When you judge the author’s argument, you discover more about not only the author’s opinion but also your own. If this step already seems daunting, remember that even the best writers need to use prewriting strategies to generate ideas.

Prewriting strategies depend on your critical reading skills. Reading, prewriting and brainstorming exercises (and outlines and drafts later in the writing process) will further develop your topic and ideas. As you continue to follow the writing process, you will see how Mariah uses critical reading skills to assess her own prewriting exercises.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming refers to writing techniques used to:

- Generate topic ideas

- Transfer your abstract thoughts on a topic into more concrete ideas on paper (or digitally on a computer screen)

- Organize the ideas you have generated to discover a focus and develop a working thesis

Although brainstorming techniques can be helpful in all stages of the writing process, you will have to find the techniques that are most effective for your writing needs. The following general strategies can be used when initially deciding on a topic, or for narrowing the focus for a topic: freewriting, asking questions, listing, and clustering/idea mapping.

In the initial stage of the writing process, it is fine if you choose a general topic. Later you can use brainstorming strategies to narrow the focus of the topic.

Freewriting

Freewriting is an exercise in which you write freely about any topic for a set amount of time (usually five to seven minutes). During the time limit, you may jot down any thoughts that come to your mind. Try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can without stopping. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over again until you come up with a new thought.

Writing often comes easier when you have a personal connection with the topic you have chosen. Remember, to generate ideas in your freewriting, you may also think about readings that you have enjoyed or that have challenged your thinking. Doing this may lead your thoughts in interesting directions.

Quickly recording your thoughts on paper will help you discover what you have to say about a topic. When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and unselfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

Look at Mariah’s example below. The instructor allowed the members of the class to choose their own topics, and Mariah thought about her experiences as a communications major. She used this freewriting exercise to help her generate more concrete ideas from her own experience.

Freewriting Example

Last semester my favorite class was about mass media. We got to study radio and television. People say we watch too much television, and even though I try not to, I end up watching a few reality shows just to relax. Everyone has to relax! It’s too hard to relax when something like the news (my husband watches all the time) is on because it’s too scary now. Too much bad news, not enough good news. News. Newspapers I don’t read as much anymore. I can get the headlines on my homepage when I check my email. Email could be considered mass media too these days. I used to go to the video store a few times a week before I started school, but now the only way I know what movies are current is to listen for the Oscar nominations. We have cable but we can’t afford movie channels, so I sometimes look at older movies late at night. UGH. A few of them get played again and again until you’re sick of them. My husband thinks I’m crazy, but sometimes there are old black-and-whites on from the 1930s and ‘40s. I could never live my life in black-and-white. I like the home decorating shows and love how people use color on their walls. Makes rooms look so bright. When we buy a home, if we ever can, I’ll use lots of color. Some of those shows even show you how to do major renovations by yourself. Knock down walls and everything. Not for me–or my husband. I’m handier than he is. I wonder if they could make a reality show about us?

Asking Questions

Who? What? Where? When? Why? How?

In everyday situations, you pose these kinds of questions to get more information. Who will be my partner for the project? When is the next meeting? Why is my car making that odd noise? When faced with a writing assignment, you might ask yourself, “How do I begin?”

You seek the answers to these questions to gain knowledge, to better understand your daily experiences, and to plan for the future. Asking these types of questions will also help you with the writing process. As you choose your topic, answering these questions can help you revisit the ideas you already have and generate new ways to think about your topic. You may also discover aspects of the topic that are unfamiliar to you and that you would like to learn more about. All these idea-gathering techniques will help you plan for future work on your assignment.

When Mariah reread her freewriting notes, she found she had rambled and her thoughts were disjointed. She realized that the topic that interested her most was the one she started with, the media. She then decided to explore that topic by asking herself questions about it. Her purpose was to refine media into a topic she felt comfortable writing about. To see how asking questions can help you choose a topic, take a look at the following chart that Mariah completed to record her questions and answers. She asked herself the questions that reporters and journalists use to gather information for their stories. The questions are often called the 5WH questions, after their initial letters.

Asking Questions Example

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Who? | I use media. Students, teachers, parents, employers and employees– almost everyone uses media. |

| What? | The media can be a lot of things– television, radio, email (I think), newspapers, magazines, books. |

| Where? | The media is almost everywhere now. It’s at home, at work, in cars, and even on cell phones. |

| When? | The media has been around for a long time, but it seems a lot more important now. |

| Why? | Hmm. This is a good question. I don’t know why there is mass media. Maybe we have it because we have the technology now. Or people live far away from their families and have to stay in touch. |

| How? | Well, media is possible because of the technology inventions, but I don’t know how they all work. |

Narrowing the Focus

After rereading her essay assignment, Mariah realized her general topic, mass media, is too broad for her class’s short paper requirement. Three pages are not enough to cover all the concerns in mass media today. Mariah also realized that although her readers are other communications majors who are interested in the topic, they might want to read a paper about a particular issue in mass media.

The prewriting techniques of brainstorming by freewriting and asking questions helped Mariah think more about her topic, but the following prewriting strategies can help her (and you) narrow the focus of the topic:

- Listing

- Clustering/Idea Mapping

Narrowing the focus means breaking up the topic into subtopics, or more specific points. Generating lots of subtopics will help you eventually select the ones that fit the assignment and appeal to you and your audience.

Listing

Listing is a term often applied to describe any prewriting technique writers use to generate ideas on a topic, including freewriting and asking questions. You can make a list on your own or in a group with your classmates. Start with a blank sheet of paper (or a blank computer screen) and write your general topic across the top. Underneath your topic, make a list of more specific ideas. Think of your general topic as a broad category and the list items as things that fit in that category. Often you will find that one item can lead to the next, creating a flow of ideas that can help you narrow your focus to a more specific paper topic. The following is Mariah’s brainstorming list.

Mariah’s Brainstorming List

Mass Media

- Magazines

- Newspapers

- Broadcasting

- Radio Television

- DVD

- Gaming/Video Games

- Internet Cell Phones

- Smart Phones

- Text Messages

- Tiny Cameras

- GPS

From this list, Mariah could narrow her focus to a particular technology under the broad category of “mass media.”

Idea Mapping

Idea mapping, sometimes called clustering or webbing, allows you to visualize your ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. This technique is also known as clustering because ideas are broken down and clustered, or grouped, together. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map:

- Start by writing your general topic in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Moving out from the main circle, write down as many concepts and terms ideas you can think of related to your general topic in blank areas of the page. Jot down your ideas quickly–do not overthink your responses. Try to fill the page.

- Once you’ve filled the page, circle the concepts and terms that are relevant to your topic. Use lines or arrows to categorize and connect closely related ideas. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

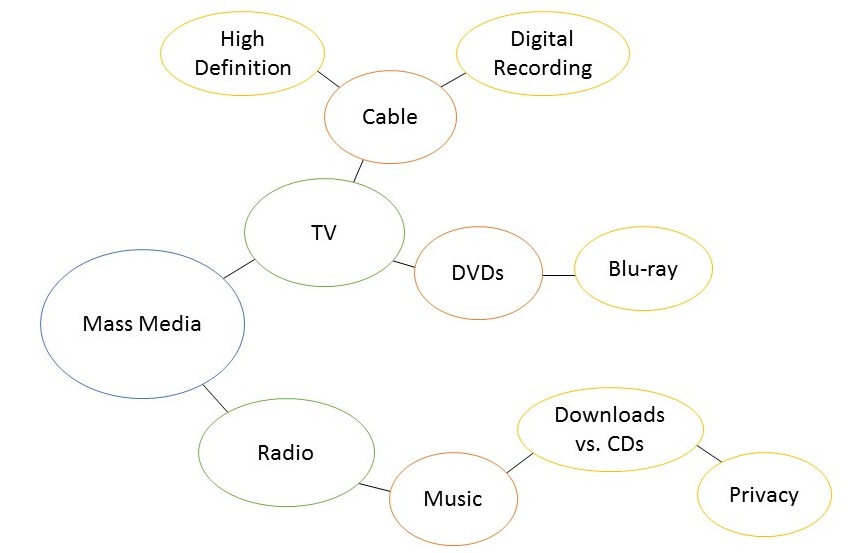

To continue brainstorming, Mariah tried idea mapping. Review Mariah’s idea map in Figure 2.5.1.[1]

Mariah’s Idea Map

Notice Mariah’s largest circle contains her general topic, mass media. Then, the general topic branches into two subtopics written in two smaller circles: television and radio. The subtopic television branches into even more specific topics: cable and DVDs. From there, Mariah drew more circles and wrote more specific ideas: high definition and digital recording from cable and Blu-ray from DVDs. The radio topic led Mariah to draw connections between music, downloads versus CDs, and, finally, piracy. From this idea map, Mariah saw she could consider narrowing the focus of her mass media topic to the more specific topic of music piracy.

Topic Checklist: Developing a Good Topic

- Am I interested in this topic?

- Would my audience be interested?

- Do I have prior knowledge or experience with this topic? If so, would I be comfortable exploring this topic and sharing my experience?

- Do I want to learn more about this topic?

- Is this topic specific?

- Does it fit the length of the assignment?

Prewriting strategies are a vital first step in the writing process. First, they help you choose a broad topic, and then they help you narrow the focus of the topic to a more specific idea. An effective topic ensures that you are ready for the next step: Developing a working thesis and planning the organization of your essay by creating an outline.

Outlining

Purpose of an Outline

Once your topic has been chosen, your ideas have been generated through brainstorming techniques, and you’ve developed a working thesis, the next step in the prewriting stage might be to create an outline. Sometimes called a “blueprint,” or “plan” for your paper, an outline helps writers organize their thoughts and categorize the main points they wish to make in an order that makes sense.

The purpose of an outline is to help you organize your paper by checking to see if and how your ideas connect to each other, or whether you need to flesh out a point or two. No matter the length of the paper, from a three-page weekly assignment to a 50-page senior thesis, outlines can help you see the overall picture. Having an outline also helps prevent writers from “getting stuck” when writing the first draft of an essay.

A well-developed outline will show the essential elements of an essay:

- thesis of essay

- main idea of each body paragraph

- evidence/support offered in each paragraph to substantiate the main points

A well-developed outline breaks down the parts of your thesis in a clear, hierarchical manner. Writing an outline before beginning an essay helps the writer organize ideas generated through brainstorming and/or research. In short, a well-developed outline makes your paper easier to write.

The formatting of any outline is not arbitrary; the system of formatting and number/letter designations creates a visual hierarchy of the ideas, or points, being made in the essay. Major points, in other words, should not be buried in subtopic levels.

Outlines can also be used for revision, oftentimes referred to as backwards, or reverse, outlines. When using an outline for revision purposes, you can identify issues with organization or even find new directions in which to take your essay.

Creating an Outline

- Identify your topic. Put the topic in your own words with a single sentence or phrase to help you stay on topic.

- Determine your main points. What are the main points you want to make to convince your audience? Refer back to the prewriting/brainstorming exercise of answering 5WH questions: “why or how is the main topic important?” Using your brainstorming notes, you should be able to create a working thesis.

- List your main points/ideas in a logical order. You can always change the order later as you evaluate your outline.

- Create sub-points for each major idea. Typically, each time you have a new number or letter, there needs to be at least two points (i.e. if you have an A, you need a B; if you have a 1, you need a 2; etc.). Though perhaps frustrating at first, it is indeed useful because it forces you to think hard about each point. If you can’t create two points, then reconsider including the first in your paper, as it may be extraneous information that may detract from your argument.

- Evaluate. Review your organizational plan, your blueprint for your paper. Does each paragraph have a controlling idea/topic sentence? Is each point adequately supported? Look over what you have written. Does it make logical sense? Is each point suitably fleshed out? Is there anything included that is unnecessary?

Sample Outline

Thesis: Moving college courses to an asynchronous online environment is an effective way of preventing the spread of COVID-19 and offers more students the opportunity to participate.

- Moving college courses to an asynchronous online environment is an effective way of preventing the spread of COVID-19.

- An online environment reduces the risk of in-person contact.

- Students don’t have to be on-campus, avoiding high-contact living situations

- Students don’t have to travel, avoiding buses and other high-contact travel environments

- Students don’t have to sit in lecture halls, avoiding extended indoor exposure

- An online environment reduces the risk of contact infections

- Students complete group work via chat rooms or online platforms.

- Students don’t have to touch shared seating, doors, etc.

- Students don’t have to share lab equipment or other materials

- An online environment reduces the risk of in-person contact.

- Moving college courses to an asynchronous online environment offers more students the opportunity to participate.

- An asynchronous course allows students to work at their own pace.

- This affords students the ability to complete coursework around a job schedule.

- This format is often family-friendly for those who have children or other familial responsibilities.

- An asynchronous course provides additional protection for those at high-risk of COVID-19

- Students may be at high risk or have family members who are high risk

- The reduced exposure of an online environment allows these students to participate without increasing their risk

- An asynchronous course allows students to work at their own pace.

Practice Activity

This section contains material from:

Crowther, Kathryn, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Successful College Composition. 2nd edition. Book 8. Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711203012/https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8/

- “Mariah’s Idea Map” was derived by Brandi Gomez from an image in: Kathryn Crowther et al, Successful College Composition, 2nd ed. Book 8. (Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016), http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

The method or operation by which something is done or accomplished; a series of continuous actions that result in the achievement of a goal. The writing process refers to the sequence of steps that result in an essay, research paper, or other piece of writing.

The person or group of people who view and analyze the work of a writer, researcher, or other content creator.

Necessary or critical for existence; indispensable or integral.

Intimidating, threatening, or fear-inducing.

To present or put forward an idea.

A statement, usually one sentence, that summarizes an argument that will later be explained, expanded upon, and developed in a longer essay or research paper. In undergraduate writing, a thesis statement is often found in the introductory paragraph of an essay. The plural of thesis is theses.

A lengthy research paper written as part of a graduation requirement for someone who is close to completing their undergraduate requirements for their major and is in their final year of undergraduate study. Like a master’s thesis or a doctoral dissertation, a senior thesis is written to demonstrate mastery over specific subject matter.

The essence of something; those things that compose the foundational elements of a thing; the basics.

Justify, affirm, or corroborate; to show evidence of; to back up a statement, idea, or argument.

A system involving rank. Hierarchical refers to a system that involves a hierarchy. For example, the military is a hierarchical system in which some people outrank others.

To be subject to the judgment of a whim, chance, or personal preference; the opposite of a standardized law, regulation, or rule.

An altered version of a written work. Revising means to rewrite in order to improve and make corrections. Unlike editing, which involves minor changes, revisions include major and noticeable changes to a written work.

Irrelevant, unneeded, or unnecessary.

Occurring at a different time; not occurring at the same time; asynchronous learning refers to work that can be done by a student independently without real-time interaction or guidance from an instructor.