IV. Types of Argumentation

4.5 Toulmin: Dissecting the Everyday Argument

Rebecca Jones and Sarah LeMire

Philosopher Stephen Toulmin studies the arguments we make in our everyday lives. He developed his method out of frustration with logicians (philosophers of argumentation) that studied argument in a vacuum or through mathematical formulations:

All A are B. All B are C.

Therefore, all A are C.[1]

Instead, Toulmin views argument as it appears in a conversation, in a letter, or some other context because real arguments are much more complex than the syllogisms that make up the bulk of Aristotle’s logical program (for a review of syllogisms see section 3.4 of this text). Toulmin offers the contemporary writer/reader a way to map an argument. The result is a visualization of the argument process. This map comes complete with vocabulary for describing the parts of an argument. The vocabulary allows us to see the contours of the landscape—the winding rivers and gaping caverns. One way to think about a “good” argument is that it is a discussion that hangs together, a landscape that is cohesive (we can’t have glaciers in our desert valley). Sometimes we miss the faults of an argument because it sounds good or appears to have clear connections between the statement and the evidence, when in truth the only thing holding the argument together is a lovely sentence or an artistic flourish.

For Toulmin, argumentation is an attempt to justify a statement or a set of statements. The better the demand is met, the higher the audience’s appreciation. Toulmin’s vocabulary for the study of argument offers labels for the parts of the argument to help us create our map.[2]

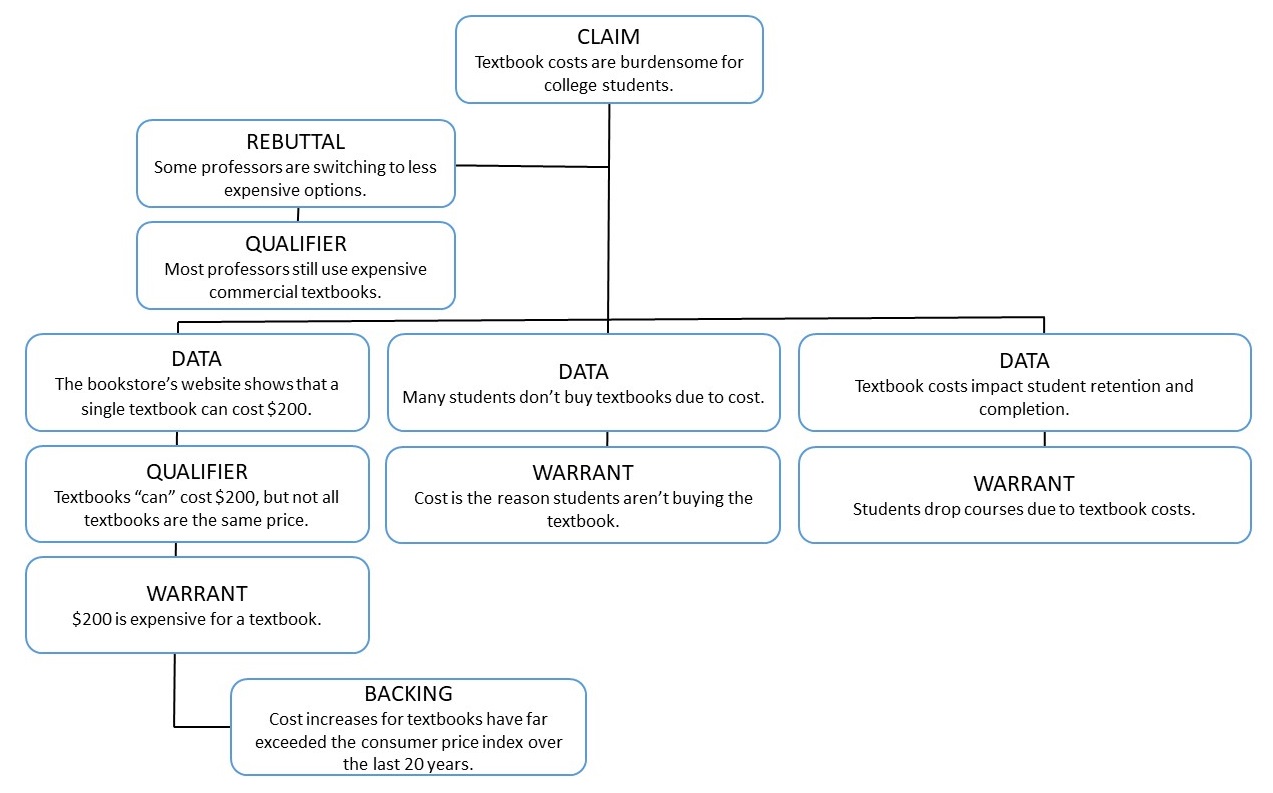

Claim: The basic standpoint presented by a writer/ speaker.

Data: The evidence which supports the claim.

Warrant: The justification for connecting particular data to a particular claim. The warrant also makes clear the assumptions underlying the argument.

Backing: Additional information required if the warrant is not clearly supported.

Rebuttal: Conditions or standpoints that point out flaws in the claim or alternative positions.

Qualifiers: Terminology that limits a standpoint. Examples include applying the following terms to any part of an argument: sometimes, seems, occasionally, none, always, never, etc.

The argument below is charted to help us to understand some of the underlying assumptions found in the argument.

Example: “The Cost of Textbooks is Ruining Students’ Lives”

The Cost of Textbooks is Ruining Students’ Lives

By Charity B. Brae

If you stop and ask virtually any college student walking across a college or university campus in the United States, they can tell you that the cost of textbooks is a big problem. Although college students and their families are well aware that the tuition, fees, and room and board costs of college attendance are enormous, many families are not fully prepared for the ridiculous cost of a textbook that students may only use for a single semester. A quick look at the campus bookstore’s website reveals that one semester’s worth of textbooks for CHEM 101 alone can exceed $200. A semester’s worth of classes can cost more than $1,000. As the cost of textbooks continues to rise, financial pressure on students continues to increase.

As a college student myself, I can attest that this financial pressure is starting to wear on students. Ansel Jalonen, a junior in the College of Engineering, declares, “I’m having to work all through winter break in order to pay for my textbooks for Spring semester. After working so hard through Fall semester, I need a mental break to get ready for Spring. But because textbooks are so expensive, I can’t. Instead, I’m getting up at 6:00 am to paint houses all through break. It’s stressful.” Other students report having to resort to other solutions to relieve the financial pressure. Esperanza Lopez, a Senior from the School of Business, notes that she hasn’t “bought a textbook since freshman year. My roommate is also in the School of Business, so I try to take the same classes as she does and she lets me borrow her book. When she needs it, I go to the library and use the copy on reserve. If it weren’t for my roommate and the library, I’d probably have to drop out because I can’t afford the textbooks.” Indeed, many students on campus report that they don’t actually buy all of their required textbooks because they cost too much.

Some professors are making an effort to reduce the cost of textbooks in their classes. Professors are switching to less expensive options, adopting free open-source textbooks, or are writing their own textbooks that students can access online for free. Professors whose classes have free open-source textbooks are marked with an “OER Textbook” notation in the course catalog so students can identify which classes have no textbook charges. But not all professors have taken advantage of these options. In fact, most professors are still using expensive corporate textbooks in their classes, despite the obvious cost to their students.

Figure 4.5.1[3] below demonstrates one way to chart the argument that Nym make in “The Cost of Textbooks is Ruining Students’ Lives.” The chart helps us to see that some of the warrants, in a longer research project, might require additional support. For example, the warrant that students drop courses due to textbook costs is an argument that would require evidence.

Example of Visualizing an Argument

Charting your own arguments and the arguments of others helps you to visualize the meat of your discussion. All the flourishes are gone and the bones revealed. Even if you cannot fit an argument neatly into the boxes, the attempt forces you to ask important questions about your claim, your warrant, and possible rebuttals. By charting your argument you are forced to write your claim in a succinct manner and admit, for example, what you are using for evidence. Charted, you can see if your evidence is scanty, if it relies too much on one kind of evidence over another, and if it needs additional support. This charting might also reveal a disconnect between your claim and your warrant or cause you to reevaluate your claim altogether.

The Toulmin method is a useful way of determining the validity of an argument and is oftentimes the model used in legal proceedings. But the Toulmin method can leave you feeling as if you’re stuck in an either/or situation as it focuses on justifying the arguer’s reasons only. For a method that incorporates a humanistic approach, consider using the Rogerian method.

Practice Activity

This section contains material from:

Jones, Rebecca. “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?” In Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1, edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, 156-179. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010. https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=243. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711204300/https://writingspaces.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Finding-the-Good-Argument.pdf.

- Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, and Francesca Snoeck Henkemans, Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation (Mahwah: Erlbaum, NJ, 2002), 131. ↵

- Stephen Toulmin, The Uses of Argument, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1958). ↵

- This image was derived from “Figure 5: This Chart Demonstrates the Utility of Visualizing an Argument” by Rebecca Jones in: Rebecca Jones, “Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?,” in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1, eds. Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky (West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010), 156-179, https://writingspaces.org/?page_id=243. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. ↵

A type of logic or reasoning associated with Aristotle involving a conclusion based on statements called premises which lead to a conclusion. A major premise is a statement of universal truth or common knowledge. A minor premise is a statement related to a major premise but concerns a specific situation. Together, major premises and minor premises form a conclusion. For example, “all dogs are mammals (major premise) and all dogs are mammals (minor premise), so, therefore, all dogs are animals (conclusion).”

To express an idea in as few words as possible; concise, brief, or to the point.