Contemplating & Exploring Ethical Considerations of Large Language Models [Resource]

C. Anneke Snyder

What You Will Learn in This Section

In this section, you will learn about the importance of ethical considerations and implications of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI), particularly Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT. This section highlights that LLMs are not inherently good or bad. Instead, the importance of user engagement in ethical practices is emphasized to ensure responsible use of these tools.

Ethical considerations for educators include attention to student privacy, expectations, and consequences—all of which should clearly be defined in syllabus statements, classroom policies, or institutional statements. Meanwhile, ethical implications exist involving varying ethical standards for how people approach LLMs differently, how human and machine bias influence GenAI, and how style guides differ on citing information garnered from ChatGPT.

After reading this section, you should be able to articulate your own ethical queries and concerns related to LLMs, such as ChatGPT, both as a general user and an educator.

This chapter is divided in the following sections. Click the links below to jump down to a section that interests you:

- Author Reflection: How has my understanding of AI evolved?

- Why do ethical considerations and implications of LLMs matter in the era of generative AI?

- How can ethical decision-making be cultivated among students in the context of LLMs?

- Can a course be ChatGPT-proof?

- What are some biases inherent in generative AI?

- Can ChatGPT be cited?

- How can pedagogical approaches reflect individual ethical beliefs and practices?

- How can educators broach topics of ethical generative AI-use with students?

- What ethical considerations should we share with our students about LLMs?

Author Reflection: How has my understanding of AI evolved?

As a teacher, Ph.D. candidate, and member of my institution’s honor council, I believed I had a clear understanding and approach to ethical practices concerning learning and research. However, upon writing this section, I found myself questioning years of standardized approaches to research and pedagogy: Who or what is an author? Can text be considered plagiarism if a writer is editing machine-generated output? Is it possible for instructors to create assignments that remove student inclination to use LLMs? And should they even do so in the first place? I am not sure that I have answers to my questions; I am not even certain that I am asking all the right questions. However, I am confident that GenAI, and specifically ChatGPT, is not going away. Rather than defining this technology as inherently good or bad, we should consider how to adapt and adjust our understanding of ethical behavior as we witness the genesis and integration of GenAI into our daily lives. Ethical behavior is not static and is largely dependent on dynamic cultural norms, behaviors, and practices. As someone whose research is grounded in studying forms of cultural preservation, evolution, and transmission, I will be watching closely to see how educators and students alike navigate the technological and cultural changes currently taking place in our society.

Anneke Snyder (see fig. 1)[1] is a Ph.D. candidate whose work focuses on Latinx, multiethnic, and transnational literatures in the Department of English at Texas A&M University.

Why do ethical considerations and implications of LLMs matter in the era of GenAI?

Can Do vs. Should Do

Questions about ethical considerations are often at the heart of conversations about Large Language Models (LLMs), and, more specifically, ChatGPT. Due to the rapid pace of technological advancements, our focus tends to be primarily on the novelty and excitement of what we can do with generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) at the expense of considering what we should do. However, as educators, contemplating the ethical implications of using LLMs within and beyond the classroom space is critical to considering not only what we want our students to learn but how they learn and apply that knowledge (see table 1).

Table 1

Reflective Questions for Educators Exploring the Integration of GenAI into their Teaching Practices

Educators should explore the ethical implications and consequences of the integration of GenAI in their own teaching practices by asking themselves the following questions:

- Will I allow my students to use any form of GenAI to complete assignments?

- In what ways will I integrate forms of GenAI into my own teaching and evaluation practices?

- How will I include my institution’s expectations, policies, and rules of conduct and integrity into my regulations and expectations regarding LLMs, a form of GenAI focused on language production?

Privacy & Confidentiality Concerns

Ethical concerns about using GenAI in the classroom should first and foremost be about user safety and well-being. Because of privacy and confidentiality concerns relating specifically to LLMs—the extent of which has not been fully realized—we caution against requiring students to use these forms of technology as part of course participation or final grades. Similarly, we caution against instructors inputting student work into LLMs, especially without student consent, as such a practice can actually violate student privacy under FERPA.

Personal Ethics Reflections

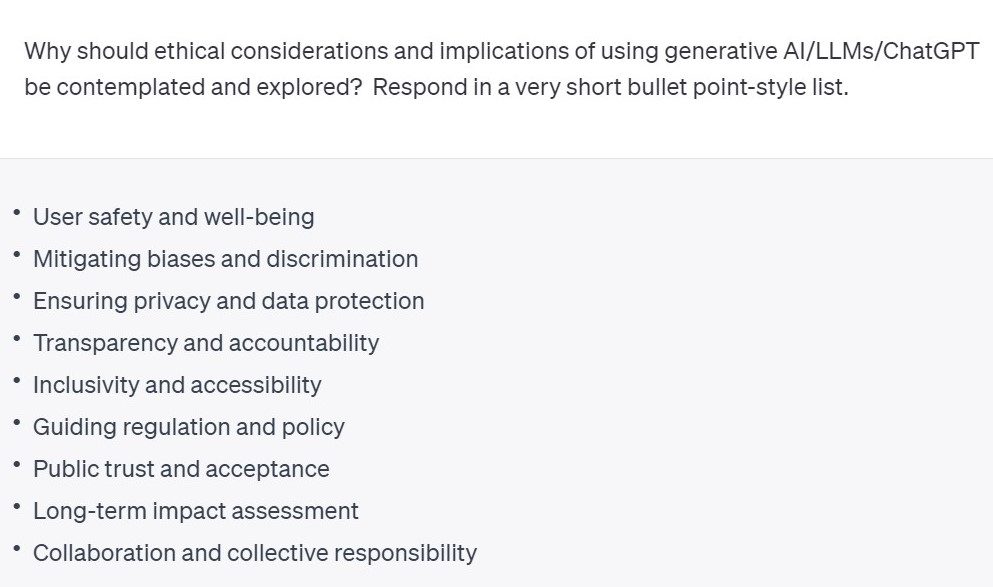

Integrating LLMs into spaces of learning and education also requires contemplating and exploring ethical issues related to academic integrity, course policy, data protection, bias, collaboration, and responsibility for learning. How, where, and why an individual educator includes or integrates these technologies into their pedagogical practices depends on their own ethical beliefs and considerations in relation to their institution’s expectations (see fig. 2).[2]

Note: Screen-readable Word version of ChatGPT’s response regarding ethical considerations.

How can ethical decision-making be cultivated among students in the context of LLMs?

Considering Different Ethical Standards

Promoting ethical student use of LLMs, specifically ChatGPT, involves navigating the complexities of AI system regulations and educator expectations. For instance, OpenAI, which governs ChatGPT’s usage and restrictions, has a policy list of disallowed usages for users. Account-holders who consistently engage in these disallowed practices may have their accounts terminated. Most of these disallowed usages involve illegal activity or doing harm to others, physical or otherwise—what the average person might call the minimum threshold for ethical or moral behavior. Yet, these disallowed usages do not necessarily prevent students from making poor choices that involve academic misconduct. Rather, they merely preclude them from engaging in activity that might result in physical and financial harm to themselves and other users.

OpenAI’s policies and processes help guard against crime and abuse. However, manipulation of ChatGPT leading to academic misconduct is not within the parameters of OpenAI’s disallowed usages. Instead, OpenAI provides an overview of the technology’s education-related risks and opportunities for educators. OpenAI leaves the decision as to what is considered ethical or unethical in an education-related environment up to individual educators. Thus, educators are the arbiters of academic integrity and misconduct.

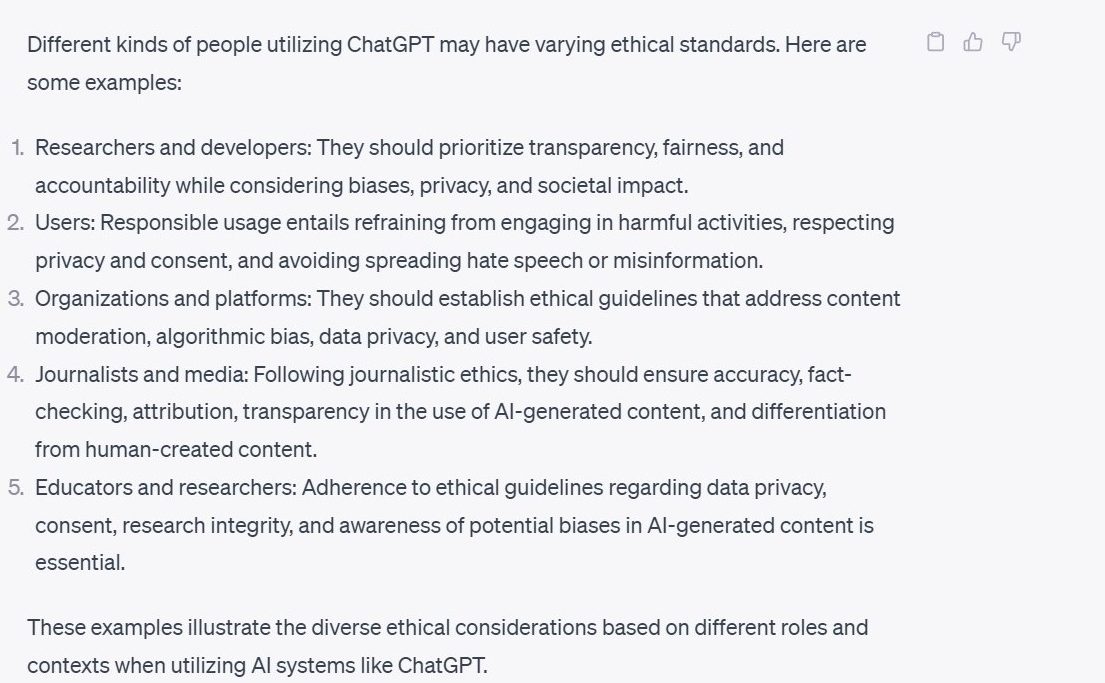

Rather than thinking in terms of absolutes—whether ChatGPT is good or bad—we encourage educators to consider ChatGPT, as well as other forms of LLMs and GenAI more broadly, as tools. The ethical standards for general user engagement with the tool may differ from those applicable to students during their educational journeys. Because of these different ethical standards, it is up to each individual educator to decide the parameters around student uses of these technologies (see fig. 3).[3]

Note: Screen-readable Word version of ChatGPT’s response regarding varying ethical standards.

Outlining Student Expectations & Consequences

Clearly outlining student expectations and consequences for using GenAI, LLMs, and/or ChatGPT—and understanding the difference between the three terms—is integral to differentiating between ethical engagement and academic misconduct. Because every course, educator, and institution is unique, each individual educator should consider how to distinctly approach GenAI in their pedagogical practices. If students are consciously aware of clear distinctions and differences between each instructor’s individual approach, they can adjust their own reading, writing, and learning practices accordingly for each corresponding course.

We strongly discourage educators from ignoring the ethical implications of LLMs because it can lead students to commit academic integrity violations, both consciously and unconsciously. Instead, we advise instructors to integrate their expectations about GenAI, LLMs, and/or ChatGPT into their classroom practices and syllabi in coordination with their institution’s (and department’s) policies. We also suggest that educators be aware of institutional student rules regarding ethics in research and scholarship. Finally, because LLMs are a relatively new and quickly-evolving technology, contacting an institution’s teaching resource center at regular intervals can allow educators to stay up-to-date on any changes regarding institutional policies or best practices involving GenAI technologies.

Syllabus Statements

Syllabi, particularly in post-secondary education, are considered to be a type of contract between instructors and students. Typically, syllabi contain information related to the course such as required texts, exam schedules, and academic integrity. Including a statement regarding an educator’s, department’s, and/or institution’s expectations of LLMs use, like ChatGPT, makes what is and is not permissible clear to students, instructors, institutional-governing bodies, and ethics committees.

Instructors who want to completely disallow the use of GenAI, LLMs, and/or ChatGPT in their courses can do so in a syllabus statement. Likewise, instructors who will allow their students to use GenAI, LLMs, and/or ChatGPT can specify when and how these technologies can be utilized in a syllabus statement. However, we caution against including a generalized statement allowing all forms of GenAI to be used at any and all times. Instead, we encourage instructors to consider the structure of their courses, the needs of their students, and their learning objectives as they craft these statements. The following resources can be used by instructors as inspiration and guidance as they craft their own syllabus statements:

- Generative AI Syllabus Statement Considerations

- Letter to Students: A Long Note About AI and Other Tools

- Sample Syllabus Statement

- ChatGPT Syllabus Statements

Classroom-Related Policies and Practices

Classroom-related policies and practices refers to the routines, protocols, and procedures incorporated into regular course meetings, lectures, and seminars. Considering when and how to include or restrict access to GenAI, LLMs, and/or ChatGPT in a typical course allows educators to have a response to most situations that may arise. Moreover, these policies and practices allow an instructor to set a tone that indicates to students what generally is and is not allowed in both minor and major assignments. The following resources can be used by instructors as inspiration and guidance as they determine which policies and practices should be incorporated into their classrooms:

- Open Compendium: Classroom Policies for Generative AI Tools

- Resource for Responding to Generative AI

- Guidance for the Use of Generative AI

- Pedagogic Strategies for Adapting to Generative AI Chatbots

Institutional Statements

Because of the exponential use and growth of ChatGPT, LLMs, and other forms of GenAI, some universities and other institutions have created statements outlining the use and restrictions of these technologies. While some of the statements are words of caution, other statements include what a university will and will not allow from its faculty, staff, and students. Some of these statements come from ethics committees or other institutionally recognized programs, such as teaching resource centers. We encourage educators to investigate whether their own institution has such a statement or is in the process of creating one. The following are institutional statements outlining university policies and concerns about GenAI:

Can a course be ChatGPT-proof?

The Short Answer

The short answer is no, a course cannot be 100% ChatGPT-proof. Moreover, it can be virtually impossible to ban or restrict the use of all forms of AI in any course. However, it is possible to mitigate the use of LLMs and other forms of GenAI, including ChatGPT. Some educators might find that giving in-class exams and requiring in-class handwritten work might mitigate the use of LLMs, specifically ChatGPT, on major assignments. However, in writing-intensive courses where all major and minor assignments are centered around student production and articulation of the written word, exams, creative projects, or handwritten work are impractical and inappropriate solutions to ChatGPT-proof a course.

Rather than thinking in terms of whether or not a course can be ChatGPT-proof, we encourage educators to consider crafting their assignments in ways that encourage critical thinking, reflection, and creativity. This might mean that instructors create an alternative assignment to the traditional research paper, form a flipped classroom, include oral exams in their courses, or construct student-centered assignments based on personal experiences. Though there is no one correct or best approach to prevent students from using, or being inclined to use, LLMs in writing-intensive courses, educators should focus on creating a course based upon the overall knowledge and skills they want students to learn rather than assignments that need to be completed. In short, we encourage educators to take this opportunity to reimagine the possibilities of what a writing-intensive course can be.

What are some biases inherent in GenAI?

Machine Bias is Human Bias

LLMs like ChatGPT are ultimately human creations. Thus, like humans, these technologies are flawed, imperfect, and subject to bias. Because GenAI, and specifically LLMs like ChatGPT, are the result of collective intelligence, the collective directs the generative responses. Moreover, the foundational system in place to gather this collective intelligence was constructed by humans who have their own thoughts, beliefs, and understandings about what information should be disseminated and eliminated. Thus, though LLMs appear to be technological tools of neutrality, they are actually likely to promote certain ideas, practices, and values at the expense of others. In short, no LLM user should consider generated responses as objective and impartial truth (see table 2).

Table 2

A Partial List of Human Biases Inherent in LLMs

Here is a partial list of human biases inherent in LLMs, specifically ChatGPT:

- Reporting Bias: Only information up to 2021 is available for ChatGPT’s average user.

- Sample Bias: Collective intelligence can only generate new and updated information drawing on user input. User input is limited to the people who engage with ChatGPT consistently rather than the entire population; segments of the population who do not engage with GenAI technology consistently will not be represented in the LLMs response to input.

- Programmatic Morality Bias: The creators of ChatGPT programmed overrides to generate socially acceptable responses or output.

- Political Bias: ChatGPT tends to generate answers that are politically left-leaning in nature.

- Overton Window Bias: The amount of information available exceeds what the GenAI actually draws from in order to appear neutral or uncontroversial.

- Ignorance Bias: Though artificially intelligent, ChatGPT cannot partake in reasoning of any sort, and, therefore, is incapable of independently asking new or related questions to an inquiry, directing the user to another relevant point, or suggesting new content tangentially related to the original topic for the user to explore.

- Deference Bias: Humans tend to defer to generated AI responses as automatically accurate or true despite evidence to the contrary.

AI Detector Bias Can Lead to Educator Bias

Biases exist in the creation, production, and generation of AI intelligence; however, biases also exist within AI detectors. In a world where it is increasingly unclear whether information is machine-generated or the product of independent human thought, it can be difficult for educators to distinguish between genuine student work and forms of academic dishonesty. As a result, AI detectors are becoming ways to help educators identify whether academic misconduct took place, yet AI detectors are themselves flawed and biased.

Most significantly, these detectors consistently misidentified text written by non-native English-speakers as AI generated. Because LLMs are created to mimic human language patterns, AI detectors can wrongly label genuine student work as AI generated. Conversely, AI detectors can also be fooled into considering AI-generated text as genuine student work. The unreliability of AI detectors leaves educators in a quandary as there is no reliable way to discern this form of academic dishonesty. Moreover, this dilemma can cause educators to form their own biases about GenAI, student work, ethics, and academic integrity. This educator bias can result in inappropriately defensive approaches to incorporating, banning, or regulating LLMs in their courses.

Unlike AI technologies, educators, as humans, have the ability to acknowledge their cognitive biases. We urge educators to reflect on their personal biases concerning AI technologies in their interactions with students and their work.

Can ChatGPT be cited?

Opinions on Authorship Differ

ChatGPT is an LLM, a form of GenAI focused on the patterns and configurations found in language usage. The language generated by ChatGPT might appear to be original text; however, it is ultimately a form of disseminated collective intelligence. Though OpenAI’s terms of use for ChatGPT claims that users own the output as well as the input (what is collectively known as Content), the fact remains that ChatGPT cannot assign output ownership or authorship; due to the nature of collective intelligence, a technology company in charge of an LLM such as ChatGPT might not own intellectual property associated with output. Moreover, as a machine rather than a human writer or researcher, ChatGPT is neither capable of nor responsible for citing sources, giving credit to an original source, or even naming the original source.

ChatGPT is not an author in the traditional sense—it cannot take responsibility for generated text or how that information is interpreted and used. But, because this generated text is also not original thought belonging to a ChatGPT user, any information garnered from ChatGPT should be cited by users who incorporate the technology into their work. The ethical practices and processes of citation, research, and accreditation depend on individual citation styles. Moreover, each of these citation styles have different approaches as to how to consider the question of authorship: MLA explicitly states that ChatGPT is not an author while APA does consider OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT, to be the author of information generated by ChatGPT.

Standards for accuracy and appropriateness may vary in different citation styles over time and that not all citation styles have announced standard citation formatting for LLMs in general or ChatGPT in particular.

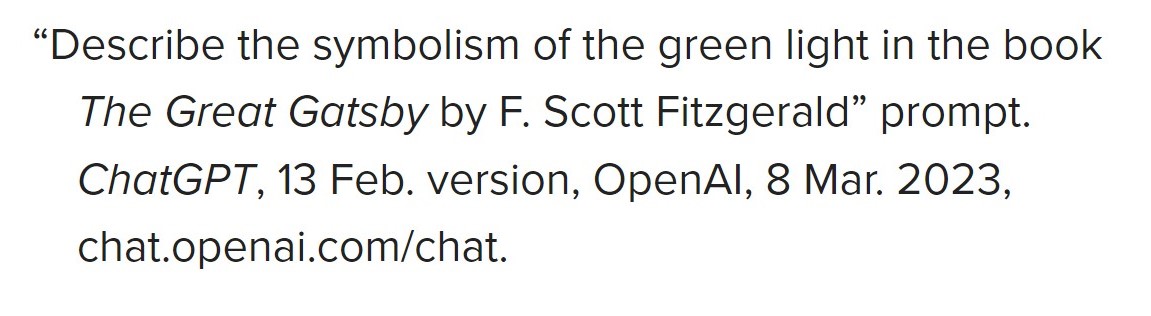

MLA Format

Traditionally, MLA adheres to the following method for citation: author, title of source, title of container, version, publisher, date, and location (see fig. 4).[4]

MLA does not recommend treating GenAI as an author, and in citations involving ChatGPT, no author should be listed. The title of a source should give some indication of the prompt or input (Why color is the sky?). The title of the container is the AI tool (ChatGPT). Version refers to the version of the AI tool (ChatGPT 3.5). Publisher is the company that made the tool (OpenAI). The date is the date the content was generated while the location is the url of the source.

MLA encourages the following practices:

- citing when paraphrasing, quoting, or summarizing GenAI text into writing

- acknowledging the used functional elements of GenAI (such as translation) in the main body of text or an endnote/footnote

- checking to ensure any sources or works it lists actually exist

Note: Screen-readable Word version of a ChatGPT citation in MLA format.

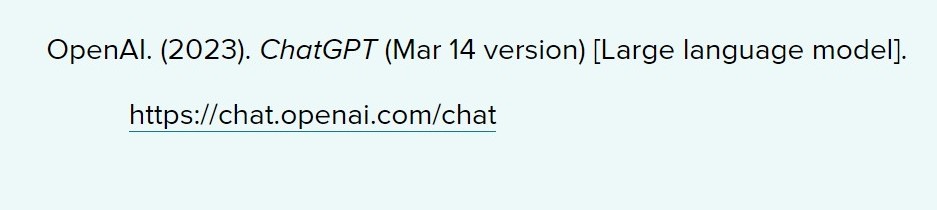

APA Format

APA is concerned with four elements of GenAI: author, date, title, and source (see fig. 5).[5]

APA considers the creator of the GenAI technology (OpenAI) to also be the author of generated information. Date is the year (not the exact day) that the technology was used. Title is the general model of technology (ChatGPT) while the version of the technology should be included in parentheses (Mar 14 version); additional information about the type of GenAI can be included in brackets (Large language model). Meanwhile, source most frequently refers to the url where the information can be accessed.

APA encourages users to also recommends the following considerations:

- full text of long responses from ChatGPT can be included in an appendix or other supplemental materials

- users of ChatGPT and other forms of GenAI should scrutinize primary sources provided, ensure these sources exist, and read these primary sources

- APA guidelines for ChatGPT can be adapted for other forms of GenAI, particularly LLMs

Note: Screen-readable Word version of a ChatGPT citation in APA format.

How can pedagogical approaches reflect individual ethical beliefs and practices?

Be Aware that Institutional Standards and Individual Nuances Exist

Though a standard of ethical practices exists within the academic community, the nuances of these practices vary among fields of study; student comprehension of ethics and integrity in required coursework may also differ. Therefore, when educators have a clear sense and understanding of their own beliefs about academic integrity and ethical practices, they can incorporate these values and principles into the expectations located in their syllabi, assignment instructions, and exam procedures.

How an individual educator considers their own ethical beliefs and practices will vary from person-to-person. However, when educators can articulate and outline these beliefs via their student expectations, their students can consciously avoid committing academic misconduct. Making sure that these expectations align with an institution’s student code of conduct and academic integrity policy is crucial to ensuring that values of ethical behavior are upheld within and beyond the classroom (see table 3).

Table 3

Questions Prompting Educators to Contemplate Their Own Ethical Beliefs About Forms of GenAI

We encourage educators to consider the following questions as they contemplate their own ethical practices and beliefs about GenAI, LLMs, and, more specifically, ChatGPT:

- Will I allow students to use GenAI or LLMs, such as ChatGPT, in my course?

- Will I consider any use of GenAI or LLMs, such as ChatGPT, plagiarism, cheating, or another academic integrity violation?

- What instructions or policies do I have in place to guide students to developing good ethical practices related to GenAI or LLMS, such as ChatGPT?

- How do my instructions or policies regarding GenAI or LLMs, such as ChatGPT, align with my institution’s practices and values?

My Ethical Beliefs in Practice: Personal Anecdotes

A Teaching Perspective

When it comes to evaluating student work, my own ethical beliefs and practices are governed by the protocols, norms, and traditions of my field as well as my institution’s rules, policies, and expectations. Because I structure my courses around written assignments and research- and creative-based projects, I understand that using LLMs contains enormous appeal for students completing the course requirements. One of the current questions I am contemplating as I consider my own ethical beliefs and practices in the era of GenAI asks where the line between academic honesty and dishonesty exists, particularly as it relates to the student-use of ChatGPT to produce written work.

As someone who sits on Texas A&M University’s Aggie Honor Council and regularly facilitates and adjudicates Aggie Honor System Office investigations, conferences, and hearings as they relate to academic misconduct and Student Rule 20, I have been, directly and peripherally, a part of the larger conversation at my institution about ethics and GenAI, specifically LLMs such as ChatGPT. Many of these conversations are centered around questions about the ethical implications of ChatGPT’s integration into student learning, how to regulate the use of GenAI, and whether AI detectors like ZeroGPT are reliable.

I have developed my own reactions, responses, and inclinations towards this line of questioning. Summarily, if academic misconduct involving LLMs occurs, the established norms, conventions, and queries pertaining to academic misconduct should and will be upheld. As with any other academic misconduct case involving prohibited materials, cheating, plagiarism, or other integrity violations, ascertaining whether or not the line between academic honesty and dishonesty exists can potentially be determined by the following questions:

- the wording of an instructor’s explicit instructions and permissions on any project, assignment, or exam

- What were the assignment instructions? How were these instructions worded?

- Did the instructor explicitly allow or disallow students to use external resources on the assignment? What were these specific resources?

- Is there a statement in the syllabus regarding the use of GenAI, such as LLMs, in the course? Did this statement indicate that any use of GenAI was prohibited in any work completed for the course?

- the requirement of citations on any project, assignment, or exam

- Did the assignment require specific citations such as APA, MLA, Chicago, or another citation style?

- Did the instructor include, either in the assignment instructions or a syllabus statement, citations of GenAI were required in the course?

Beyond these two guidelines, I have come to recognize my own concern with the traditional language found in student rules of academic conduct (Student Rule 20 at TAMU). That is, because ChatGPT is a generator of language, an LLM, rather than an author and creator, it cannot take on human-like qualities, particularly those that involve creativity and critical thinking. However, because student rules of academic misconduct were created before the genesis of LLMs, it can be tempting to personify these technologies so that the language can align with policies and regulations. Whether the language within student rules of misconduct should be altered or adapted to consider LLMs is a question that all institutions must eventually contemplate (see table 4).

Table 4

Ethics in Practice: Contemplating Plagiarism

Despite its use of the personal pronoun “I” to refer to itself, ChatGPT is not “another person.” Copying and pasting from the LLM would not be considered plagiarism under section a (20.1.2.3.5.a) or section c (20.1.2.3.5.c) of TAMU’s Student Rule 20 definition of plagiarism. However, if an instructor explicitly required students to cite ChatGPT (or any other resource) if it was used, not citing such information from the LLM could fall under plagiarism under section b (20.1.2.3.5.b) and section d (20.1.2.3.5.d) of TAMU’s Student Rule 20. However, if an instructor did not explicitly require such a citation, whether or not plagiarism actually took place is potentially a matter of debate under section e (20.1.2.3.5.e) of TAMU’s Student Rule 20.

An Embodied Perspective

LLMs like ChatGPT offer the possibilities of global connectivity as ubiquitous communication tools. Yet, as we come closer together through their use, discerning which voices are centralized and which ones are marginalized becomes a critical area of examination. My role as an English instructor means I propagate Standard English in my pedagogy. Simultaneously, as the granddaughter of circular immigrants and a heritage Spanish-speaker, I recognize that the language I use outside of the classroom differs greatly from the language I use within it.[6] That is, in my role as daughter, cousin, and friend, I am likely to lace my English with Spanish and use the colloquial collection of words commonly referred to as Spanglish in daily communication. However, my reality is not reflected in the language generation inherent in LLMs, nor is this reality reflected in curriculum I am often required to teach, which means our society suffers a cultural loss.

Embodied experiences inform language production, and lived experiences influence our interactions through words and language. However, we must recognize that the unique nature of these embodied experiences can further marginalize gendered, multicultural, and multilingual encounters that already exist on the periphery of society. Because the nature of LLMs like ChatGPT pull from the text representing a collective mass of experiences that then becomes codified and disseminated, minority experiences are overlooked in favor of majority voices. Consequently, the resulting imbalance exacerbates existing social disparities and reinforces the need for more inclusive and representative AI technologies in our educational and societal systems. What educators can already witness in classrooms specifically and institutions of higher learning more generally–the standardization of both language and curriculum–is more significantly present in the underlying nature of LLMs: They fail to accurately represent rich human experiences. While ChatGPT claims it can, it cannot truly engage in a conversation that combines multiple languages or effectively convey the idea that certain concepts and experiences are untranslatable across different languages.[7]

What makes the standardization of language within LLMs troubling are the impacts beyond academia, the physical classroom space, and the formal training of a student who graduates with specialized knowledge. LLMs like ChatGPT can be used unknowingly, unwittingly, and unwillingly to speak for and about the experiences of marginalized people. Essentially, LLMs can act as a form of ventriloquism in which those of the majority produce language that speaks for the silenced minority. This ventriloquism creates forms of language loss, and perhaps more urgently, contributes to the flattening of rich and complex personal experiences that are centered on material reality. Within a physical classroom space, bodies represent components of the learning environment, and embodied experiences become part of the educational experience, however minor. This physical presence helps to complicate the standardization of language and curriculum as students are able to bring their personal experiences into their work. As educators, it is our responsibility to determine how to instruct our students in using GenAI while also highlighting that it cannot substitute for in-person learning. Additionally, as educators, we must work to differentiate the nuances between material human experiences within the context of machine knowledge and the inherent risks and biases associated with LLMs.

How can educators broach topics of ethical GenAI-use with students?

Establish Clear Instructions & Expectations

Ultimately, educators cannot control or regulate student use of the many forms of GenAI, including LLMs like ChatGPT. Students must make their own decisions about whether to engage in academic misconduct or uphold academic integrity. What educators can do is establish clear expectations for coursework and give detailed instructions about what kinds of GenAI use are and are not permissible on each assignment (see table 5). Furthermore, educators should elucidate the importance and necessity of citing ChatGPT and other forms of GenAI to encourage students to get into the habit of citing such sources.

Table 5

Questions Guiding Students Towards Ethical Use of Generative AI

We suggest that educators pose the following questions to their students so they can understand the ethical implications of using various forms of GenAI, including LLMs, such as ChatGPT:

- Does my institution have an academic integrity policy regarding forms of GenAI, specifically LLMs, such as ChatGPT? Am I adhering to this policy in the coursework that I complete?

- Does the instructor allow forms of GenAI, specifically LLMs, such as ChatGPT, to be used in completing some or all parts of the assignment? What do the instructions say about incorporating GenAI into my response?

- If I used a form of GenAI, specifically an LLM such as ChatGPT, in an assignment, did I properly cite this information according to the citation style required by my instructor?

- Am I participating in academic integrity or academic misconduct as I complete my coursework?

- How can I ethically engage with GenAI and other emerging technologies? What do I consider my ethical responsibilities to be regarding these technologies?

What ethical considerations should we share with our students about LLMs?

Educators can use the language in table 6 to share an abbreviated version of this section with students.

Table 6

Ethical Concerns and Implications About LLMs to Share with Students

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) is just like any other tool—whether it is used with good or ill intentions depends on the user. As students, it is up to you to decide how you will use this tool on your educational journey. You might find that use of GenAI is allowed and even encouraged by some of your instructors. You might also find that some of your instructors will prohibit the use of GenAI to complete coursework. You should always listen to your instructors and heed their expectations when it comes to these new and emerging technologies so that you can avoid committing academic misconduct. However, the final decision on whether or not to use GenAI, just like the tool itself, is in your hands.

Before engaging with GenAI, and specifically Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, you should be aware that there are different ethical standards, expectations, and implications for different kinds of usage. As students, not only should you adhere to the policies of the companies that create and run these technologies, but you should also adhere to your institution’s regulations regarding student research and learning practices. These practices often include citing the use of LLMs, particularly ChatGPT; if you are unsure whether citation is necessary, know that it is always best to cite information garnered from LLMs as a way to safeguard your academic integrity.

Finally, you should ask yourself how much you know about GenAI, particularly commonly used LLMs like ChatGPT. Bias, misinformation, and misrepresentation is inherent in LLMs like ChatGPT. Gaining awareness of your personal ethical concerns and adopting specific approaches towards these emerging technologies will provide you with a consistent guiding framework for your interactions with them.

Attribution:

Snyder, C. Anneke. “Contemplating & Exploring Ethical Considerations of Large Language Models [Resource].” Strategies, Skills and Models for Student Success in Writing and Reading Comprehension. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2024. This work is licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Images and screenshots are subject to their respective terms and conditions.

- Anneke Snyder, "Image of author enhanced with Photo to Art: BeFunky," 2023. ↵

- ChatGPT, Screenshot of the prompt and response to “Why should ethical considerations and implications of using GenAI/LLMs/ChatGPT be contemplated and explored? Respond in a very short bullet point-style list,” 2023, OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com/ ↵

- ChatGPT, Screenshot of the response to the prompt “Are there different ethical standards for different kinds of people utilizing ChatGPT? Include examples in the response.” 2023, OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com/ ↵

- MLA Style Center, "An Example of a ChatGPT Citation in MLA Format," Screenshot, March 17, 2023, https://style.mla.org/citing-generative-ai/?fbclid=IwAR0RNnDOPQzIMeZjJ5AJMV1O0MJgQDNbZO7b4-8UNAlwi0crXhawKq4Ev1c. ↵

- Timothy McAdoo, "How to Cite ChatGPT," screenshot, APA Style, April 7, 2023, https://apastyle.apa.org/blog/how-to-cite-chatgpt?fbclid=IwAR1KbHYv5gkGjrHa--MH-kjPN7PnOh6r1fBZ50LYKsDva_syFPgwXYTywS8. ↵

- Circular immigration is a term used to refer to immigrants who frequently migrate between two countries, often generationally. In the context of my family history, circular immigration refers to the travel between the United States (south Texas) and Mexico (northern Tamaulipas). ↵

- The linked conversation generated by ChatGPT is inspired by the three languages I speak: English, Spanish, and Mandarin Chinese. ↵