Incorporating Large Language Models into the Writing Process [Resource]

Gwendolyn Inocencio

What You Will Learn in This Section

In this section, illustrative examples from ChatGPT show how to incorporate Large Language Models (LLMs) into the writing process while considering ethical concerns associated with such tools, namely avoiding plagiarism or exploitation of AI-generated content. The advent of public access to LLMs means they are now a critically important aspect of digital information literacy. As such, this technology must be addressed in the composition classroom with guided instruction. We recommend a strategy that models application of a modified version of stasis theory to all LLM-generated content.

After reading this section you should be prepared to teach stasis theory as a strategy for continual interrogation that helps rhetors discern whether generative-AI content exhibits appropriate depth, scope, and quality, along with the appropriate next steps in argumentation, writing, or research.

This chapter is divided into the following sections. Click the links below to jump down to a section that interests you:

- Author Reflection: How has my understanding of AI evolved?

- How can Large Language Models facilitate the writing process?

- How can stasis theory help students analyze LLM-generated content?

- Is LLM use cheating?

- Who owns the LLM content, though?

- How can educators guide students in using LLMs in the writing process?

- What considerations should we share with our students about incorporating LLMs into the writing process?

Author Reflection: How has my understanding of AI evolved?

Fig. 1: Personal image enhanced with PicsArt

This writing project was born of necessity. As a composition instructor, I began my research bewildered by AI technology and Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, and their profound effects on the craft of writing instruction. Situated behind the curve on this emergent technology, I quickly resolved to learn how LLMs operate and how they can (and must) be recognized as tools that students will use—like it or not! As a rhetorician, I located solace from my deep uncertainty in antiquity, from Plato’s communication of Socrates’ argument against writing as a new technology, inferior to the spoken word. Socrates’ perturbed reaction to a profound shift in communication reminds me that change is the only constant in humanity’s arc. Additionally, history teaches that lamenting change is time wasted.

Immersing myself in teaching forums and listening earnestly to those in the pedagogical landscape who both lament and welcome this technology, I placed LLMs and their ilk squarely in the category of digital information literacy, which immediately clarified my role as student guide in effective and ethical use of a tool that irrevocably disrupts approaches to and teaching of writing. Good, bad, harm, and benefit will surely result from AI use in the world at-large and the composition classroom specifically. Nonetheless, returning again to the ancients, I now recognize my writing instructor role as the midwife Socrates saw himself to be: I aim to help students birth their unique ideas, voice, and (hopefully) cultivate wisdom under my guidance, using whatever tools available.

Better to roll up our sleeves, put our heads together, and tackle the proliferation of AI-generated content in an ever-changing digital world as a community of professionals than try to deny technological potential based on staunchly rigid principles. We must decide where to stand firm, but also where our processes can accommodate change. Let’s do this!

Gwendolyn Inocencio (see fig. 1) is a Ph.D. candidate teaching rhetoric and composition and technical and professional writing in the Department of English at Texas A&M University. She uses rhetorical genre studies to analyze texts addressing the complex rhetorical situation of climate catastrophes.

How can Large Language Models facilitate the writing process?

Use Large Language Models with Caution and Strategy

All writing instructors know the struggle of starting a writing project from an unformed idea. This uncertainty is where generative Artificial Intelligence (AI), in the form of Large Language Models (LLMs), facilitates invention by offering a powerful boost to the writing process—for both instructors and students. Likewise, as a generative tool trained on the internet, as a collective of human consciousness, LLMs can then be used to facilitate each step of the process, beginning with brainstorming and moving into final edits.

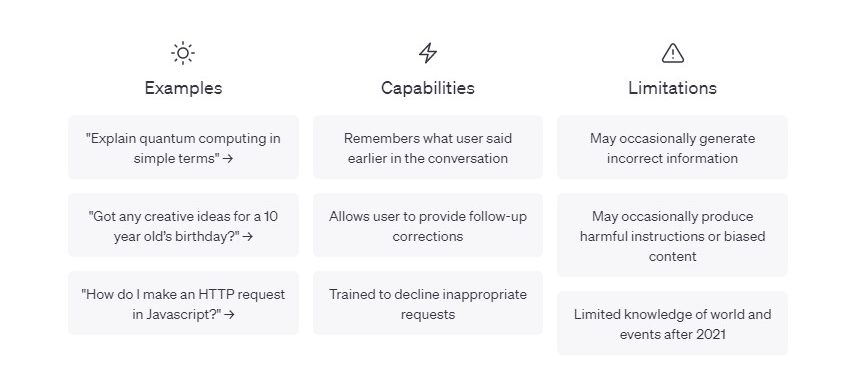

Users must understand LLMs, such as ChatGPT, work as statistical algorithms incapable of human-like thinking and consciousness, but their convincing use of machine learning to mimic human language can encourage inappropriate personification. LLMs will even hallucinate facts in an effort to fulfill a prompt. In fact, ChatGPT freely warns that it is capable of incorrect, misleading, offensive, or biased information (see fig. 2).[1] Additionally, most LLMs currently draw from knowledge prior to 2022, which could exclude the current events typically important to a rhetoric and composition course.

As a result, we suggest instructors invite the technology into their classroom with well-informed, guided instruction. We recommend a strategy that demonstrates a modified version of stasis theory applied to all LLM-generated content.

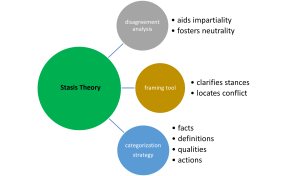

Fig. 2. Opening page to ChatGPT warning of limitation regarding accuracy and bias

Stasis theory, taught in rhetoric and composition courses, offers a method for continual interrogation of the factual integrity of generated information. Used with LLM-generated content, stasis theory helps rhetors to discern whether this content exhibits appropriate depth, scope, and quality, along with the appropriate next steps in argumentation, writing, or research. Originally used as an analysis tool for disagreements, it can be adjusted to this different context. With this adjustment, stasis theory offers not only disagreement analysis, but a useful framing tool, and an applicable categorization strategy for analysis of any generative AI content (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Three key Components of Stasis Theory as an Approach to AI-Generated Content Analysis

How can stasis theory help students analyze LLM-generated content?

Stasis Theory as a Paradigm

Stasis theory is typically used to judge where two opposing arguments break down into an impasse or stand still. The point of stasis theory is to move out of stasis (inaction) and into action. With modification, the theory offers a paradigm for illuminating any limiting factors of LLM-generated content (e.g., incorrect, misleading, offensive, or biased information).

Stasis Theory Explained

Stasis theory as a rhetorical tool dates back 2,000 years to ancient Greek and Roman courtrooms where its theoretical principles guided speakers, stuck at an impasse, a way forward. Stasis theory helps to locate the crux of the issue. The four stases are fact or conjecture, definition, quality, and policy. Taken as a sequence of questions about an issue, the essence of that issue becomes clearer and the rhetor’s path forward more easily discerned. Table 1 shows the four classical stases typically listed as an ordered sequence of questions:

Table 1

Classic Stasis Theory Questions

- What are the facts of the situation? Is truth or conjecture present?

- How (or is) the issue properly defined?

- What qualities (or values) are represented? High, low, good, bad, broad, or narrow?

- What next action is required?

With slight modification, however, this sequence of questions works quite well when applied to LLM-generated content. For example, when presented with a chatbot-generated answer to a question, instructors or students should immediately find themselves in stasis, that is, unsure whether the information is incorrect, misleading, biased, or potentially offensive. Interrogating the content with variations of the stases questions will then exhibit critical thinking and demonstrate rhetorical agency. Consider analyzing LLM-generated information using these adapted steps from stasis theory in table 2:

Table 2

Steps Adapted from Stasis Theory

- Establish the content’s factual integrity.

- Consider whether the content has appropriate depth, scope, clarity, etc. in defining the matter.

- Evaluate the content quality, such as appropriate tone, attitude, word choice, etc.

- Plan next steps in the writing/research process.

Stasis Theory Applied to AI-Generated Content

A key point when incorporating LLMs into the writing process is that LLM-generated information should always be interrogated, never taken as ready for use. The four categories of stasis theory questions provide a starting point for vetting whether the chatbot-generated info is trustworthy based on facts, definition, quality, and ability to move forward. See table 3 for a more detailed listing of modified stases questions that demonstrate the five questions approach using who, what, when, where, and why.

Table 3

The Five Questions Approach–Who, What, When, Where, Why–Applied to Stasis Theory

| Who? | What? | When? | Where? | Why? | |

| Fact | Who created these facts? (Do they reveal a confirmation bias?) | What do these facts reveal about the topic? (Are these facts disputed?) | When were these facts created? (Are they timely and relevant to the topic?) | Where did these facts originate? (Are sources discernable and trustworthy?) | Why include these facts? (Are other facts being ignored?) |

| Definition | Who created these definitions? (Do they reveal a confirmation bias?) | What do these definitions reveal about the topic? (Do they employ the appropriate key terms?) | When were these definitions created? (Are they timely and relevant to the topic?) | Where did these definitions originate? (Are sources discernable and trustworthy?) | Why include these definitions? (Are other definitions being ignored?) |

| Quality | Who is affected by this topic? (Are key stakeholders considered?) | What value attributes are revealed in this content? (How is my attitude toward the topic affected?) | When are power structures evident/hidden, valued/devalued, or highlighted/diminished in this content? | Where are critical priorities revealed and certain stances privileged? | Why include these qualities? (Do these qualities match my values associated with this topic?) |

| Actions | Who should care about this topic? (Consider the broader impact of the topic.) | What is the most appropriate action in relation to the topic? | When should action occur? (Is timely or future action called for?) | Where is the call to action located and by whom? (if evident) | Why should action be taken? (Why does this topic matter?) |

Adapted Stasis Theory in Action

Using ChatGPT, or any preferred chatbot, students can start the writing process with simply one generated response. Applying the adapted stasis theory to chatbot-generated information requires analysis in four steps:

Establish Factual Integrity

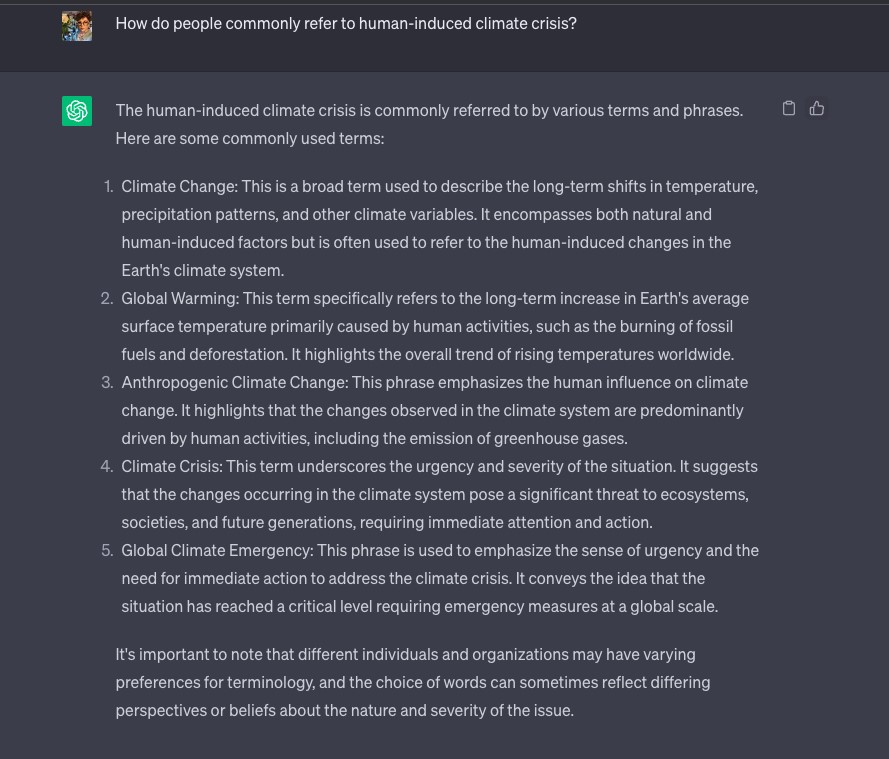

The first step to apply the modified stasis theory questions calls for validating the content as factually correct. Figure 4[2] shows that even when asking a question in the most basic format, such as asking for a list of terms, a user might find a generative research path from an uncertain starting point. For example, when a chatbot suggests common terms used to refer to human-induced climate crises, a user could examine each generated term’s origin, such as climate change and global warming, along with the subset of the population who employs that term. In this way, students would use this technique to decide if the information is factually correct or potentially misrepresented.

Consider Definitional Scope

Second, students could decide if a generated term list is comprehensive. Further questions might arise, such as “How do groups who deny human-induced causes describe climate change?” or “Are these groups who deny the human-induced premise a relevant perspective to the topic?”

Evaluate Qualities

Next, students could analyze the generated language to judge its qualities or the quality of the content as a whole. Do the rhetorical choices within its presented format highlight the information in a helpful way, such as noting each term’s emphasis?

Plan Next Steps

Finally, students can decide where they go next from this information analysis. What questions are answered or remain unanswered by this content?

Fig. 4. ChatGPT generated terms used to describe human-induced climate crisis

Stasis Theory Addressing the Copy/Paste Issue that Leads to Plagiarism

Modeling stasis theory to evaluate LLM-generated content asks the user to stand still (in stasis) with the information, to interrogate it, before moving forward with what works, leaving behind what does not, and/or refining the question for a better answer. Initially, if LLMs are used, instructors might require students to demonstrate this questioning process in writing. However, continually enacted in this way, the modified stasis theory becomes an ingrained mental process, a move toward discouraging simple copying and pasting content without regard to factual integrity, topic appropriateness, quality, or how to proceed in logical next steps.

Is LLM use cheating?

With Proper Student Training, an LLM is a Powerful Writing Tool

To use LLMs effectively, it is important to understand how they factor into their larger categorization within GenAI. Through knowledge engineering and representation, coupled with natural language processing, the goal for AI is to move toward “general intelligence,” defined as learning, reasoning, generalizing, and inferring meaning. Inspired by the human brain’s neural networks, AI is remarkably adept at simulating human thinking when responding to any request, such as to create a recipe, to answer a question, to respond to a writing prompt, or to write a surprisingly adept essay—a writing instructor’s worst-case scenario. Indeed, technology like ChatGPT is particularly primed for writing tasks. As a text-based LLM programmed to “serve” the user, it is programmed to provide the best response to any question or command.

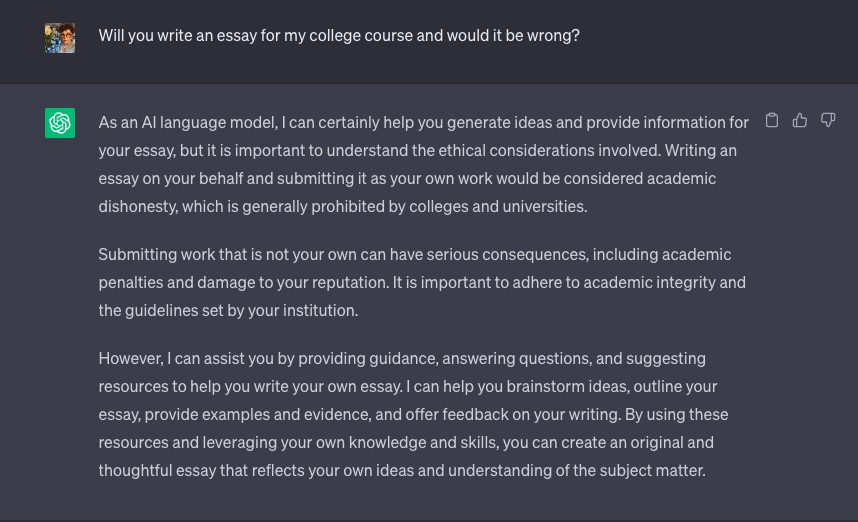

Currently, it is nearly impossible to establish beyond doubt whether AI has been used in a writing assignment, and it is predicted that AI models, such as LLMs like ChatGPT, will only progress in their ability to better process and produce human language. Therefore, instructors must train students in appropriate LLM use as a key component in digital information literacy, so students can view LLMs as yet another enhancement tool rather than simply a production tool (see fig. 5).[3] If used properly with careful consideration and continually inserting a human brain into the invention and quality control process, LLM-generated content can be a powerful tool that boosts human creativity, and no one is better qualified to teach students how to use writing tools than writing teachers. In fact, teaching such a skill becomes the writing instructor’s purview when considered a component of digital information literacy, likened in importance to teaching proficiency in searching a database or evaluating source quality.

Fig. 5. ChatGPT responds by reiterating its role as an assistant and guide when asked to whether it is wrong to request that it write a course essay

The Research or Writing Process Can Begin with an LLM

One initial approach to guiding student LLM use is its incorporation into the research and writing process. This approach begins by acknowledging LLMs as easily accessible (for some) and widely applicable (for most) to the creative process. However, beginning the process with an LLM requires knowledge of effective question and prompt construction.

A carefully constructed question or prompt is a concrete starting point to begin a project. Constructing the components of a rudimentary inquiry engages and guides students, whether large group or individually, in starting the creative process of invention. For example, instructors could model how to ask ChatGPT a formative question regarding a course topic, followed by applying the stasis theory questions to interrogate the subsequent response and then to decide next steps. Likewise, using a prompt to create an AI-generated visual will model the important role of well-chosen descriptors in the inquiry process. However, note that the response generated from the question and the visual generated from the prompt will be only as good as the question or prompt that produced it. This principle is based on the computing concept of “garbage in, garbage out,” also known as GIGO.

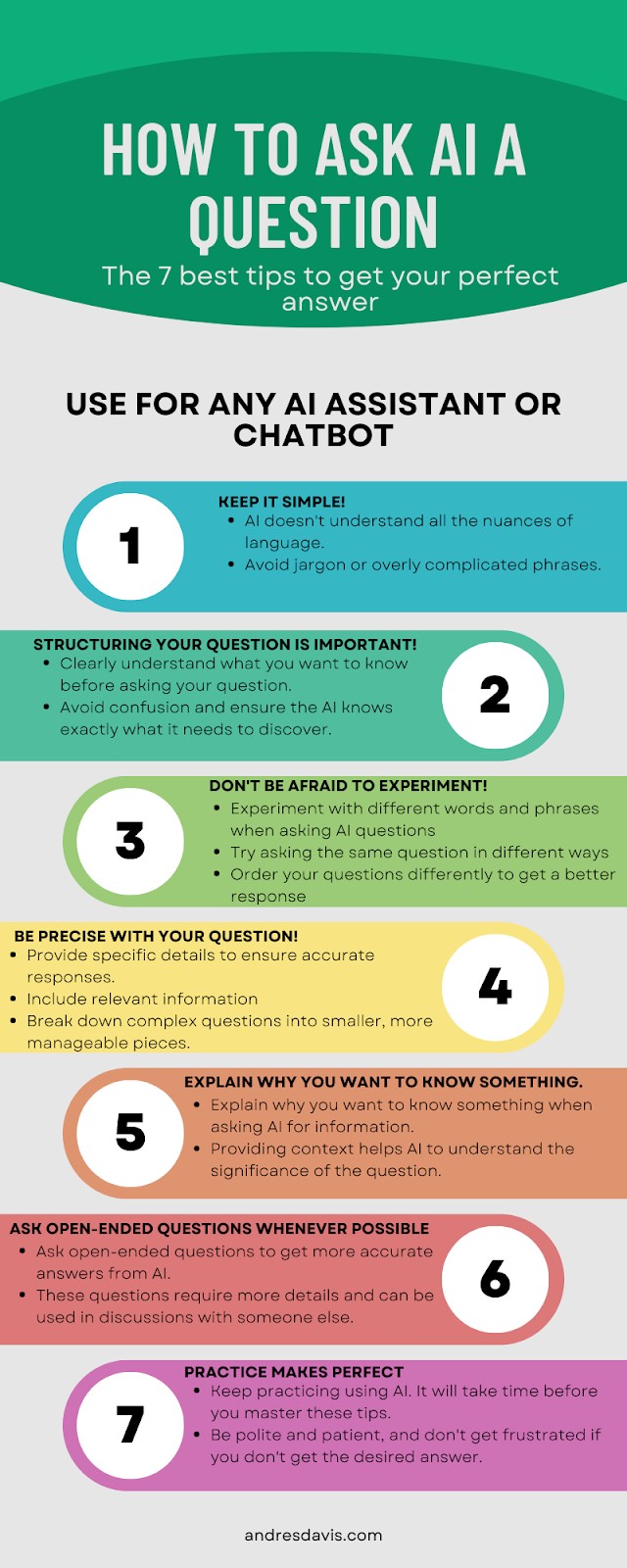

Asking a Well-Constructed Question is an Important Start

Just as Google can answer questions, locate sources, and enhance general learning, LLMs can generate starting points for the writing and research process that lead to the critical thinking fostered in the composition and rhetoric classroom. However, chatbots, such as ChatGPT are much more than glorified search engines; they are sophisticated AI that mimics human intelligence using conversationally styled requests and answers. Starting with a well-constructed question requires higher-order thinking and makes LLMs, like ChatGPT, a powerful launchpad for a research project. The seven steps in figure 6 provide a good model to guide students in question formation. It illustrates the need for simplicity, careful structuring, and precise wording. Additionally, including the why behind the question helps the tool match the best response to the question, and keeping questions open ended can increase accuracy. Lastly, the tool invites prompt experimentation through refining words and phrases, and students increase their prompt proficiency with practice.

Fig. 6. A multi-colored visual representation of the seven tips for asking AI a question, used with permission by Andre Davis

Analysis of a Response to a Well-Constructed Question Leads to Further Research

The response gleaned from the carefully constructed question provides a starting point to apply the modified stasis theory. After checking the veracity of the information, students will see if or where the response is deficient in defining the topic and/or communicating its qualities. Likewise, the AI response could offer an interesting twist to the topic not previously considered. For example, a student researching the role of agricultural practices on climate change might unexpectedly discover that monocropping becomes their primary research focus. In this way, students contemplate their next steps: exploring new contours of the topic, further refinement of key terms, tightening of the topic’s parameters, etc. Students can then decide what aspect of the generated content interests them and begin to consider an approach for further research with instructor guidance.

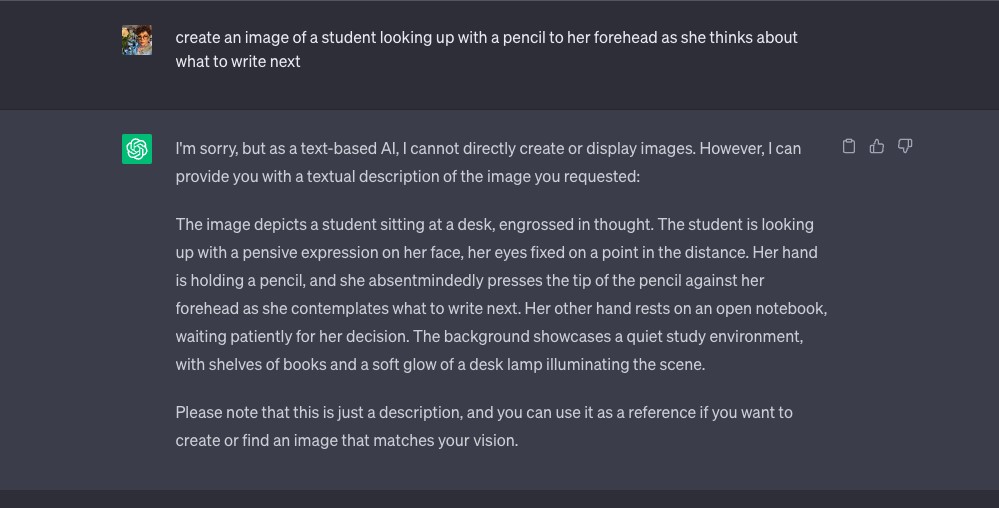

Visuals Require Different Prompts than Text Requests

Just as a well-constructed question should glean an engaging response leading to further research, the initial question and generated response could be enriched with a visual exploration of the topic. However, because ChatGPT is strictly a text based LLM, it cannot create visuals. For example, asking ChatGPT to create an image will elicit a response asserting its inability to fulfill such a request. Nonetheless, in an effort to remain helpful, it will likely expand the prompt in a more descriptive manner, useful for creating the desired image with another tool (see fig. 7).

Fig. 7. ChatGPT response to a request to create an image

Visual Prompts Supplement Questions in the Research and Writing Process

An AI image generator, such as DALL-E2, is needed to create a visual representation of a text prompt. Though DALL-E2 is not free to use, other free generators exist. For example, using PicsArt, a student could create a photo of a decimated forest to contrast with an image of an old growth forest, potentially leading to analytical thinking through comparison or juxtaposition (see figs. 8 and 9). The conversation images can generate around topics, (e.g., surrounding the impact of deforestation in the current climate crisis) demonstrates higher-order human thinking because the human provides the creative vision while the computer provides assistance (e.g., a helpful boost for those inept at drawing). In this way, visuals can enhance the creative process with options beyond describing a mental image with words.

Figs. 8 and 9. A decimated forest beside an old growth forest created with PicsArt

Guided by carefully-constructed questions and information generated through LLM collaboration, students can amass sufficient knowledge and resources to begin the outlining process, another step where LLMs like ChatGPT can assist their thinking and research process.

LLMs Can Assist with Outlining

LLMs can generate standard outlines with ease, which is not necessarily problematic in a writing classroom because outlines typically use a basic order: an introduction followed by body paragraphs and ending with a conclusion. For example, fig. 10 shows the Earth resembling a floating marble in black space.

Using the image of the Earth as a blue marble depicted in fig. 10, OpenAI’s application program interface generated the following outline in table 3:

Table 3

Standard Outline for Analysis of blue marble Earth Image

Create an outline for an essay about the visual analysis of the blue marble photo of the earth:

- Introduction

- Definition of Visual Analysis

- Description of Blue Marble Photo

- Analysis of Visual Elements

- Color

- Shape

- Texture

III. Interpretation of Visual Elements

- Color

- Shape

- Texture

- Conclusion

- Summary of Visual Analysis

- Reflection on the Significance of the Blue Marble Photo

The generated outline in table 3 provides a basic starting point for a rough draft or further research. With refinement, however, the outline can encompass a more complex approach as detailed in table 4:

Table 4

Standard Outline Arguing Against Personifying Nature

Create an outline for an essay that argues nature should not be personified:

- Introduction

- Definition of Personification

- Overview of Nature Personification

- Argument Against Nature Personification

- Nature is Not Human

- Nature is Not Conscious

- Nature is Not Intentional

III. Examples of Nature Personification

- Ancient Greek Mythology

- Modern Poetry

- Conclusion

- Summary of Argument

- Reflection on the Impact of Personifying Nature

The outlines in tables 3 and 4 take different approaches to different frames of topic reference, which means they can be combined, disassembled, and/or rearranged as needed. Creating a prompt from a different perspective, encountered through researching the first two outlines (see tables 3 and 4), could lead to yet a third iteration, shown in table 5:

Table 5

Standard Outline Incorporating a Different Perspective

Create an outline for an essay that argues climate weirding is the most appropriate topic for human-induced climate change:

Introduction

- Definition of Climate Weirding

- Overview of Human-Induced Climate Change

Argument for Climate Weirding

- Climate Weirding is More Accurate

- Climate Weirding is More Accessible

- Climate Weirding is More Inclusive

Examples of Climate Weirding

- Extreme Weather Events

- Unusual Seasonal Patterns

Conclusion

- Summary of Argument

- Reflection on the Impact of Climate Weirding

With further refinement (see table 6), varied perspectives can be layered into the outline:

Table 6

Standard Outline with Layered Perspectives

Create an outline for an essay that argues climate weirding is the most appropriate topic for human-induced climate change but considers opposing views:

Introduction

- Definition of Climate Weirding

- Overview of Human-Induced Climate Change

Argument for Climate Weirding

- Climate Weirding is More Accurate

- Climate Weirding is More Accessible

- Climate Weirding is More Inclusive

Examples of Climate Weirding

- Extreme Weather Events

- Unusual Seasonal Patterns

Counter Arguments

- Climate Change is Too Complex

- Climate Weirding is Too Vague

Conclusion

- Summary of Argument

- Reflection on the Impact of Climate Weirding

Finally, as shown in table 7, particular methods of argumentation can be woven into the mix for deeper consideration:

Table 7

Standard Outline with a Specific Method of Argumentation

Create an outline for an essay that argues climate weirding is the most appropriate topic for human-induced climate change but considers opposing views using the Rogerian method of argumentation:

Introduction

- Definition of Climate Weirding

- Overview of Human-Induced Climate Change

Summary of Opposing Views

- Climate Change is Too Complex

- Climate Weirding is Too Vague

Common Ground

- Recognition of Climate Change

- Need for an Appropriate Term

Argument for Climate Weirding

- Climate Weirding is More Accurate

- Climate Weirding is More Accessible

- Climate Weirding is More Inclusive

Examples of Climate Weirding

- Extreme Weather Events

- Unusual Seasonal Patterns

Conclusion

- Summary of Argument

- References

As the examples in tables 3-7 illustrate, LLM-generated outlines can be incorporated into the writing process to simplify or complicate topics as needed. Though OpenAI’s application program interface generated these outlines, students must still produce the writing that builds the outlines’ organizational structures. In this way, GenAI can assist the early stages of the writing and research process, which then positions students to begin drafting, followed by editing and revising.

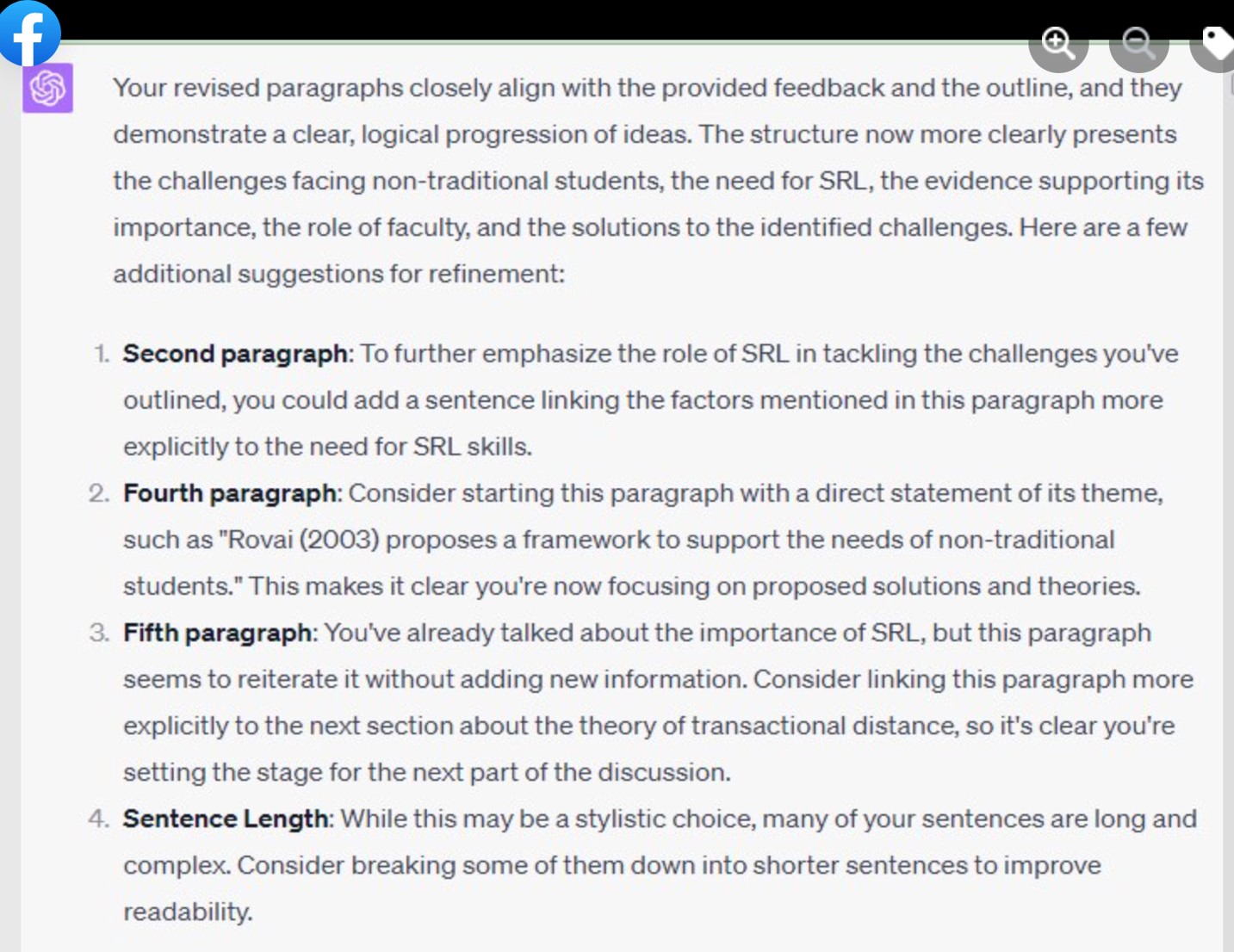

Careful Prompts Differentiate Editing Versus Revising

As students progress to actual drafting, LLMs can provide useful input for editing and revising. Simple editing for spelling, grammar, and syntax errors results from a clear prompt requesting those tasks. However, with regard to revising, one caveat is to clearly ask for revising rather than a rewrite of the material. Table 8 shows an example of a clearly written ChatGPT prompt for revision input that makes roles, parameters, and goals explicit:

Table 8

Prompt Requesting Revision by Alexis Smith Guethler in Higher Ed Discussions of AI Writing, Facebook. 7/9/23, 12:35pm

“Hello, as an AI editor, I need your assistance with a section of my research work that I’ve recently revised. My goal is to improve the clarity, coherence, and flow of ideas in this section, which is intended to [briefly describe the purpose/goal of the section]. Here are the revised paragraphs (insert revised text).

Could you, in your role as an editor, provide feedback on the following aspects:

- Logical progression and flow of ideas across paragraphs.

- Clarity and cohesion within each paragraph.

- Explicitness and effectiveness of the arguments/points made.

- Readability of sentences and phrases.

- Transition and linkage to other sections or themes.

Please remember the primary goal is to refine and polish the existing content, not to introduce new ideas or concepts. I’m looking for constructive criticism, clarifying questions, and practical suggestions for improvement. Thank you.”

If provided with clear instructions that demonstrate a precise request, ChatGPT can give paragraph-by-paragraph feedback highlighting micro-level concerns, such as sentence length. Fig. 11 shows the elicited reply from such a thorough request:

Fig. 11. ChatGPT’s suggested revisions in response to Alexis Smith Guethler’s prompt in Higher Ed Discussions of AI Writing, Facebook. 7/9/23, 12:35pm

The key point to remember with student use of LLMs for revision is to protect the student’s voice and guard against the flattening of any original thinking by inflecting it with stilted language, gleaned from the internet. Instructors must, therefore, train their students to ask for specific revision assistance commensurate with instructor and peer feedback.

Who owns the LLM content, though?

LLM Content Has Tricky Ownership Concerns

In the realm of AI, Content is defined as input and its resulting output. It is important to remember that LLM Content is “owned” by the user who generated it, according to current terms of use with ChatGPT for example. However, ownership is still a complicated matter because LLMs pull information from other intellectual property with no capability to assign particular authorship. As a result, the user who generates the question, and the resulting output, owns and is responsible for the Content, yet the data generator retains that same Content for LLM training purposes.[4] In other words, the Content, in the form of the question (input) and response (output), becomes data with no privacy protection. Additionally, depending on the particular question or prompt, the information can be inaccurate or inappropriate to the task, target audience, or intended purpose. For example, see the interestingly odd visual interpretation of the basic prompt “Show an image of AI helping a student to write” in fig. 12. The amalgamation of a human with machine-like appendages and human appendages with writing tools illustrates that this technology is still grappling with basic image requests.

Fig. 12. A human finger with a pencil oddly protruding from it and a human girl with a robotic hand, both pointing to a text, created with PicsArt

Generated Content is Only a Starting Point

Another ownership concern stems from commonly asked questions that can generate standard responses, as in “Why is grass green?” Such concerns mean that generated content is only a starting point rather than an end result in the writing process. Users must evaluate the content and build upon ideas rather than simply copying and pasting responses. As a result, LLM Content should never take the place of careful thinking, nor should the goal of a composition student or composition task be simply to edit LLM-generated content into acceptable use.

The goal of instructor-led and student-use of LLMs is to relegate generated content as a starting point to advance through the writing process–with a human brain doing the heavy thinking–via strategic analysis. With this human-centered goal entrenched in their working philosophy, students can then create strongly voiced writing that includes the appropriate ethos, pathos, and logos required for their audience. This approach, guided by critical thinking, gives students process ownership despite LLM assistance.

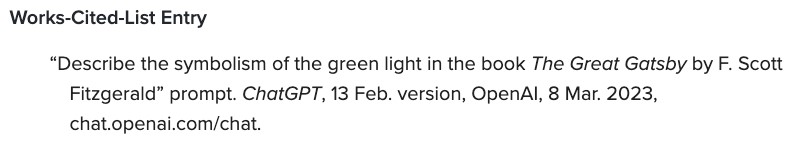

Authorship and Citation Styles Differ

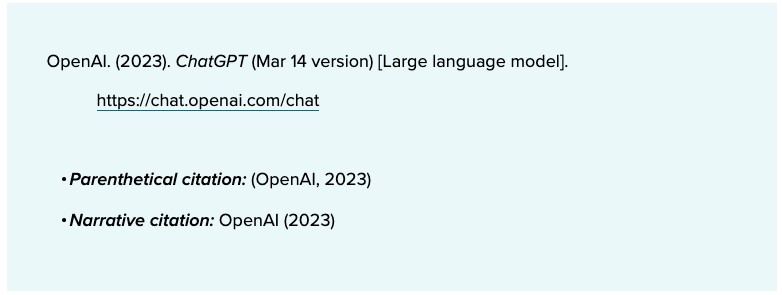

Academic writing is an amalgamation of ideas, whether borrowed, modified, shared, or reworked. As a result, the writing process requires citing the sources for any inspiration, cooperation, or appropriation. Different citation styles serve different fields by privileging the ordering of information based on the most relevant field criteria. Currently, the two most used citation styles in the humanities have differing views on AI-generated content authorship. For example, MLA “do[es] not recommend treating the AI tool as an author.” In contrast, APA does recommend citing AI as the author. In figs. 13 and 14 below, note the two common citation styles, MLA and APA, that capture differing views of AI authorship:

Fig. 13. MLA citation example for citing LLMs

Fig. 14. APA citation example for citing LLMs

Both MLA and APA citation formats require that the source be noted anywhere information is quoted, paraphrased, or summarized, whether it be text, image, or data. MLA requires that the title of the authorless source contain a description of the question or prompt. APA, however, requires the creator of the AI model be named as the author and the AI software as the title.

How can educators guide students in using LLMs in the writing process?

Instill a Cautious Approach Backed by a Strategy

This section of the module attempted to show how LLMs can be a generative tool to jumpstart the writing process, but also how they must be used with caution and a strategy. Aided by such a tool, a student may never again suffer from the blank-screen syndrome (see fig. 15).

Fig. 15. A young girl stares pensively at a blank computer screen with her chin resting on her palm, created with Imagine.Art

AI technology, in the form of LLMs, has changed the landscape of writing pedagogy and how students produce writing. One worry among writing instructors is that student reliance on generated content will eliminate the valuable process of critically thinking through a topic from brainstorming worked through to a final piece of edited, revised, and polished writing.

The current hype around LLMs is warranted because they can do much for the writing process, but without the authors of the world contributing their unique writing to the human collective that is the internet, some predict that LLMs will hit a recursive wall, known as machine drift, rendering LLM content more recognizable as computer generated and more error prone. Therefore, writing instructors must first educate themselves about the general issues surrounding this technology so students can make higher-order decisions about how or where to implement LLMs into their writing. Second, instructors must actively engage this new tool into the writing process to prepare students for the fields and job markets that will likely require them to use the technology as a productivity tool in their future careers.

What considerations should we share with our students about incorporating LLMs into the writing process?

Educators can use the language in table 9 to share an abbreviated version of this section with students.

Table 9

Consideration of LLM Use in the Writing Process to Share with Students

AI-generated content can be an antidote to the blank-screen syndrome because it acts as an exchange of information leading to action. As long as you can start with a carefully-constructed question, interrogate the response, and move forward, then the writing process has begun. In reality, you are speaking to the internet and receiving back a scan of language threads on that topic. What you can generate from that starting point is as unique as the question asked. However, depending on that question, similar answers may be generated for different users, which leads to ambiguity around content ownership. Different citation styles, such as MLA or APA have different concepts of authorship regarding content ownership, so verify instructor preference and field requirements as required. Consider analyzing all LLM-generated information using these adapted steps from stasis theory:

- Establish the content’s factual integrity.

- Consider whether the content has appropriate depth, scope, clarity, etc. in defining the matter.

- Evaluate the content quality, such as appropriate tone, attitude, word choice, etc.

- Plan the next steps in the writing/research proc

Attribution:

Inocencio, Gwendolyn. “Incorporating Large Language Models into the Writing Process.” Strategies, Skills and Models for Student Success in Writing and Reading Comprehension. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2024. This work is licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Images and screenshots are subject to their respective terms and conditions.

- ChatGPT, "Opening Page," Screenshot, OpenAI, 2023, chat.openai.com ↵

- ChatGPT, Response to "How do people commonly refer to human-induced climate change?" screenshot, June 2023, OpenAI, chat.openai.com. ↵

- ChatGPT, Response to "Will you write and essay for my college course and would it be wrong?" screenshot, June 2023, OpenAI, chat.openai.com. ↵

- It is important to note that ethical concerns regarding ownership create contentious relationships between digital content creators and the apparatus that trains computer models. ↵