Operational & Theoretical Overview for Using a Large Language Model [Resource]

Mary Landry

What You Will Learn in This Section

This section is designed to build confidence about what Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) means for the future of education by closely studying the operations, limitations, and theoretical value of a Large Language Model (LLM) like ChatGPT. To this end, this section seeks to explain what language modeling is and how this process contributes to an LLM’s tendency to generate inaccurate information. Additionally, this section considers how the design of an LLM—specifically, the collective knowledge it is trained upon—can contribute to the perpetuation of biases. Lastly, this section encourages critical thinking about the value of an LLM from a theoretical standpoint regarding the writing process and collaborative learning. By the end of this section, you should be able to articulate how an LLM like ChatGPT operates, as well as the value and limitations of this design within the evolution of learning.

This chapter is divided in the following sections. Click the links below to jump down to a section that interests you:

- Author Reflection: How has my understanding of GenAI evolved?

- What does GenAI mean for the future of education?

- What is ChatGPT? How does it even work?

- Why does it make stuff up though?

- If it generates inaccuracies, why even use it?

- Why should educators share operational and theoretical considerations with students?

- What operational and theoretical considerations should educators share with students?

Author Reflection: How has my understanding of GenAI evolved?

The work of this section is a centaur—part me, part ChatGPT. This hybridity is the natural embodiment of the theoretical ideas I discuss: working with ChatGPT as a collaborator to augment the self-dialogue in my writing, all the while navigating its operational and ethical limitations. I wrote, and ChatGPT revised. I posed different questions, and ChatGPT generated new angles. I received external feedback, and ChatGPT produced possible ways to address the feedback. So the work went on—a fusion of human intuition and AI insights. In truth, this synergy was familiar to me. As an individual with Usher’s Syndrome—a genetic condition that affects eyesight and hearing—I already live in a blended world of balancing my deaf gain and peripheral blindness within normative expectations and environments. To live in such a blended world, being able to adapt has been an essential skill—sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. I have been both empowered by adaptation and made keenly aware of societal norms that necessitate adaptation. With this experience, I approach ChatGPT the same way I approach captioning devices at a movie theater: How can technological progress be a source of empowerment rather than forced adaptation? The answer lies in prioritizing human needs—in all their shapes and sizes—at the center of responsible AI development. With humans at the center of technological progress, we just might encounter a true centaur—the best of both worlds.

Mary Landry[1] (see fig. 1)[2] teaches rhetoric and composition at Texas A&M University, where she is a Ph.D. student studying social-emotional pedagogy and disability studies within the Department of English.

What does GenAI mean for the future of education?

The Ever-Changing Landscape of Education

The answer is cloudy for the future, but it’s clear from the past that education has always been influenced by progress. From tectonic shifts like Brown v. Board of Education to the technological tsunami of the Internet, the landscape of teaching and learning is constantly evolving. For some time, artificial intelligence (AI) has marked a new chapter in this evolution (see fig. 2) with AI-powered programs as familiar as the plagiarism detector TurnItIn or the language learning app Duolingo; however, OpenAI’s public release of ChatGPT in November 2022 has triggered an AI earthquake in education.

Specifically, ChatGPT (and its chatbot counterparts, such as Anthropic’s Claude, Microsoft’s Bing, and Google’s Bard) has brought the revolutionary potential of GenAI in education to the forefront of popular conversation; broadly speaking, ChatGPT can generate content, feedback, guidance, simulations, and more. These possibilities have prompted both marveling and hand-wringing around what education should even look like.[3] In the face of such rapid, technological progress, educators can build confidence by studying ChatGPT—what it is, how it operates, how it can be ethically and responsibly used—as a generative tool. With a more thorough understanding of GenAI’s ability to produce content, educators can be more prepared for the various opportunities and situations they may encounter in this ongoing technological evolution of education (see figure 2).[4]

What is ChatGPT? How does it even work?

Large Language Models (LLMs)

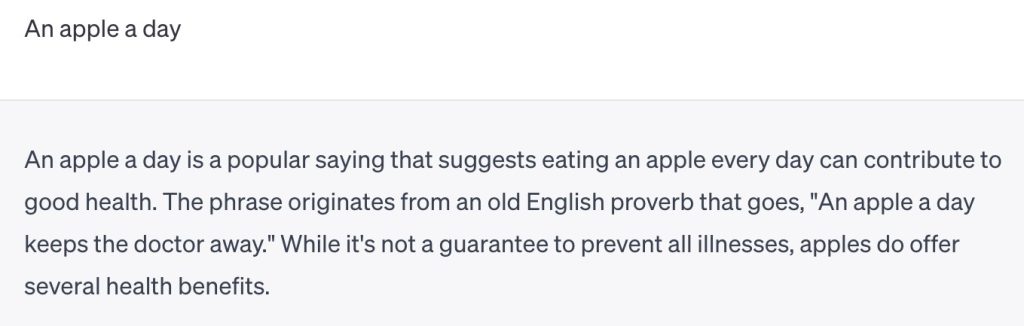

In its current iteration as of September 2023, ChatGPT is a sophisticated computer program equipped with a neural network architecture known as GPT-3.5 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3.5). This set of neural networks—the “brain”—has been trained on a vast array of text from the internet, including books, articles, and websites. As part of this training, ChatGPT “learned”[5] to predict the next word in a sentence based on the context and previous words—a process known as language modeling. For example, Figure 3[6] captures a user giving ChatGPT the prompt “An apple a day.” Predicting that the most relevant response is the rest of the saying, ChatGPT answered with “keeps the doctor away.” By training on such a large and diverse dataset, the model “learned” to generate high-quality text in a wide range of styles and topics. In other words, when a user “talks” to ChatGPT, the model uses its vast knowledge of language and context to generate output that is relevant and coherent based on the input.[7]

Note: Screen-readable Word version of the “an apple a day” prompt and “auto-complete” response.

Why does it make stuff up though?

The Right Words, but the Wrong Answer

Because ChatGPT is a Large Language Model (LLM), it is focused only on generating coherent and relevant language in response to a user’s input. Coherence and relevance does not equate to accuracy. Economist David Smerdon captures this issue in a Twitter thread that discusses how ChatGPT often makes up fake answers when a user prompts it with a fact-finding question such as “What is the most cited economics paper of all time?”.[8] As an LLM has no understanding of the underlying reality for such input, it would respond with the statistically most likely language to be correct within the context of the prompt. When one is looking for a very precise answer (as the case might be for the most cited economics paper), the statistical margin for the correct output dramatically decreases. Yet, an LLM will still attempt to fulfill the prompt, which can result in the generation of a “hallucination“[9]—that is, false information.

In the case of Smerdon’s example prompt—“What is the most cited economics paper of all time?”—ChatGPT generated a coherent and relevant (yet nonexistent) title: “A Theory of Economic History” by Douglass North and Robert Thomas. In this hallucination, the chatbot pieced together the words that statistically appear most often in economic papers that are highly cited (e.g. theory, economic, history). Then, it picked out authors that are statistically highly cited and often cited together within the field. Even OpenAI acknowledges this limitation of its software with the statement that: “ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers.“[10]

If it generates inaccuracies, why even use it?

To Mine the Collective

Even though ChatGPT cannot be relied upon for accuracy, it can still be useful as a linguistic lifeline. Consider the sea of text a person is immersed in on any given day, whether they are writing a text message, scrolling through social media, searching Google, and more. Amid this language-rich landscape, an individual can use ChatGPT to mine the AI’s collective knowledge to find the “right words” for any given purpose or task.

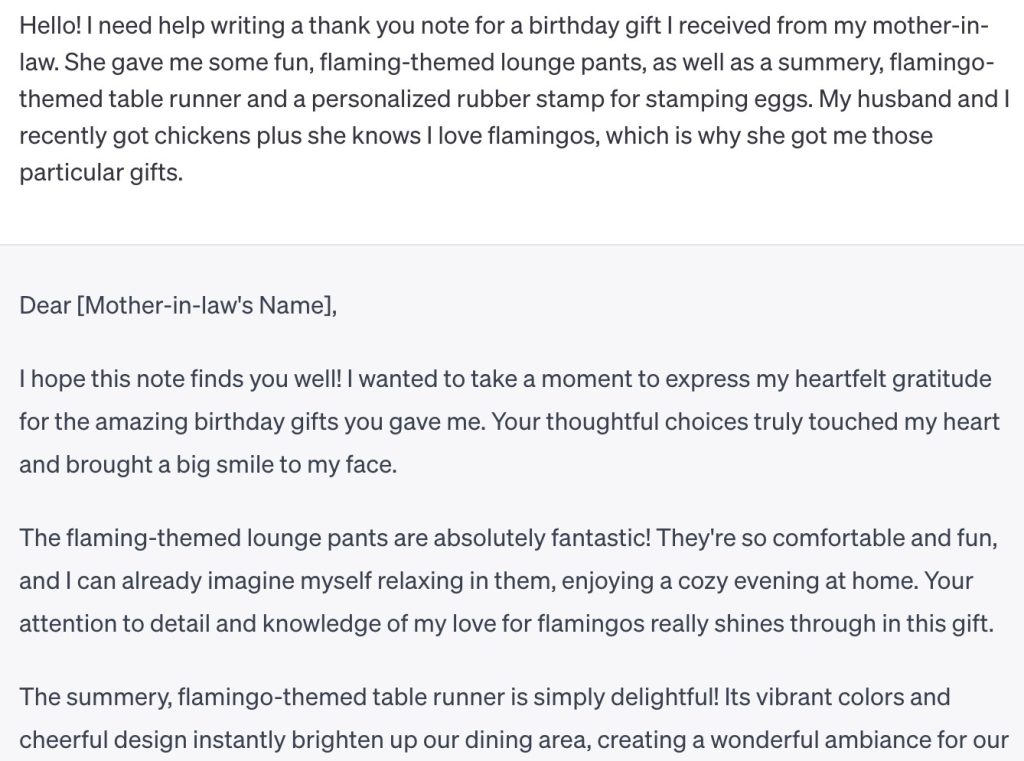

Figure 4[11] provides an example of this theory in practice, in which a user asks ChatGPT for help finding the “right words” to write a thank you note to their mother-in-law for a birthday gift of flamingo-themed lounge pants. With this information, ChatGPT generated language commonly seen in birthday-related thank you notes, such as describing how the user is currently enjoying the gift, while also customizing the text to reflect the specifics of the prompts, like so: “The flamingo-themed lounge pants are absolutely fantastic! … I can already imagine myself relaxing in them.”

Note: Screen-readable Word version of using ChatGPT to “mine the collective” for a thank you note.

While it is useful to view ChatGPT as a repository of collective knowledge, it is important to also consider the bias inherent in such knowledge. As it collects human language, it packages it in the human biases that created it. For further conversation on this risk, see table 1.

Table 1

A Note on the Dangers of Bias in the Collective

Behind such great capabilities of LLMs like ChatGPT lies an even greater truth: They can reflect humanity’s uglier flaws. Specifically, ChatGPT’s command of language comes from large training data, which have been derived from the vast wilderness of the Internet—including its most shadowy paths. In essence, if garbage goes into training a LLM, garbage will come out (GIGO).[12] In an effort to prevent ChatGPT from generating feral content from these dark corners, OpenAI employed Kenyan workers, earning less than $2 an hour, to identify and rate toxic content.[13] While these measures aim to reduce garbage output, biases within our language have deeper roots than what is easily detectable. Consequently, if the data used to train the GenAI reflects the biases sown into society, the model’s output possesses the power to amplify and perpetuate those biases further. To ensure the ethical use of GenAI technology, constant evaluation and mitigation of these biases is imperative.

To Engage in Self-Dialogue Within the Writing Process

Since composition scholar Donald Murray advocated for teaching writing as a process rather than a product in 1972,[14] First Year Composition (FYC) classrooms have embraced this approach by encouraging students to engage writing as a recursive practice. This pedagogical focus on recursivity reflects what is happening cognitively during writing. Humans process and produce language through prediction and association, much like a LLM[15] (see table 2 for a word of caution related to this fact). In this context, writing is a means of refining language production, where the act of putting thoughts into words can clarify and organize ideas. Thus, writing creates recursive thinking, which then creates recursive writing. Through writing, an individual thinks more critically about ideas, which in turn creates more conscientious writing.

If writing can serve as a tool for refining one’s thinking, it can be seen as a self-reflective internal conversation. That is, we are using writing to talk ourselves through our thinking. By incorporating a LLM like ChatGPT to this recursivity, the potential for self-reflective growth expands exponentially. In a sense, ChatGPT functions as a powerful linguistic mirror, offering a vast repertoire of language to practice in front of. It can be that voice to dialogue with when thinking aloud with words on paper.

Table 2

A Word of Caution Against Using LLM-Detection Tools

Policing a student’s collaboration with ChatGPT—sanctioned or not—through software such as GPTZero is dangerous for the same reason ChatGPT is useful as a thinking partner: its language production mimics the way humans produce language.[16] While this similarity is not absolute (and does not account for a number of other complex variables that go into language production), it is fundamentally close enough that trying to police AI-generated work has routinely produced false positives and false negatives.[17] Moreover, it will always be possible for an LLM to generate text with the specific intent of evading these sorts of detectors.[18] For further reading, consider Stefan Bauschard’s article “How I Defeated an AI Plagiarism Detector with 2 Words” [19]

To Learn in Collaboration

Consider also that engaging with an LLM like ChatGPT is a form of collaborative learning, which plays a crucial role in the learning process according to the social-cultural theoretical roots of learning proposed by Lev Vygotsky in 1978. In essence, collaboration creates a potential for learning in ways that surpass the capabilities of any individual member alone.[20] When one’s collaborator is ChatGPT, the potential for learning expands to the size of its vast, collective linguistic knowledge.

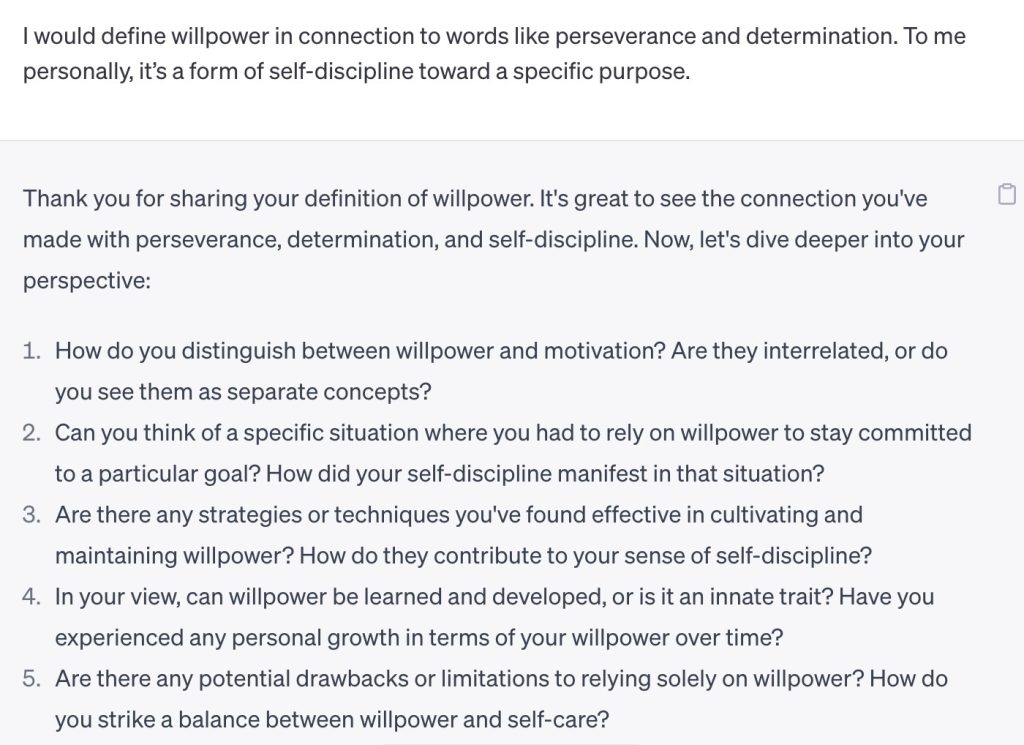

Figure 5[21] provides an example of this theoretical application, in which a user has asked ChatGPT to help her think more deeply about the concept of willpower. In this context, the user prompted ChatGPT with her definition of willpower—“To me, it’s a form of self-discipline toward a specific purpose”—to which ChatGPT responds with questions to probe her thinking further, such as “Can you think of a specific situation where you had to rely on willpower to stay committed to a particular goal? How did your self-discipline manifest in that situation?” In this manner, ChatGPT provides a source of collaborative learning that facilities the potential for growth beyond the user’s individual capabilities.

Note: Screen-readable Word version of collaborating with ChatGPT to think more deeply about “willpower”.

Why should educators share operational and theoretical considerations with students?

Keeping the Human—not Technology—at the Center of Learning

In the fast-paced, digital world students live in today, ChatGPT is old news[22] (read: yesterday’s TikTok) at this point. Yet, an educator can still encourage students to slow down and think critically about what LLMs can and cannot do, especially in the context of a college writing class. John Maeda, the director of the MIT Media Lab, provides a starting point for this discussion. In a 2006 “Humanist Technologist” blog post,[23] Maeda highlights the contrasting motivations between a ‘technologist’ (‘I do because I can’) and a ‘humanist’ (‘I do because I care’). Discussing this “can” vs. “care” distinction can remind students that it’s not just about what this generative technology can do, but why and how it should ultimately serve and augment the human experience. In other words, it’s paramount to always keep the human element at the heart of their educational journey.

What operational and theoretical considerations should educators share with students?

Educators can use the language in table 3 to share an abbreviated version of this section with students.

Table 3

Operational and Theoretical Considerations Regarding LLMs to Share with Students

The future of education in the age of GenAI is a complex and evolving landscape. With the emergence of ChatGPT and other GenAI tools, it’s important to critically understand what these tools can and cannot do in a college composition classroom.

ChatGPT is a sophisticated language model trained on vast amounts of text from the internet. It can generate a coherent and relevant response to a prompt. However, it is important to recognize the limitations of this design. While its responses may be coherent, it’s routinely shown to generate inaccuracies. Additionally, its output can be influenced by biases present in its training data, which can perpetuate societal stereotypes.

Theoretically, there are valuable ways in which ChatGPT can enhance the learning experience. It can serve as a linguistic lifeline, providing a writer with a vast collective of knowledge to find the right words for a task. Additionally, it can be a collaborator during the writing process for thinking more critically and producing more thoughtful writing.

If you engage with ChatGPT, remember to be aware of its limitations and potential biases. Use it as a supportive aid while always applying your critical thinking skills. Keep yourself—the human, not the technology—at the center of your learning journey.

Attribution:

Landry, Mary. “Operational & Theoretical Overview for Using a Large Language Model [Resource].” Strategies, Skills and Models for Student Success in Writing and Reading Comprehension. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2024. This work is licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Images and screenshots are subject to their respective terms and conditions.

- "Mary Perkins – Department of English." College of Liberal Arts at Texas A&M University, https://liberalarts.tamu.edu/english/profile/mary-perkins/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- "Image of the author generated by AI-photo app Lensa." Lensa. Lensa Terms of Use: https://tos.lensa-ai.com/terms. ↵

- Marche, Stephen. “The College Essay Is Dead.” The Atlantic, 6 Dec. 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-ai-writing-college-student-essays/672371/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- Stable Diffusion, "An AI-generated by Stable Diffusion capturing the concept of a new chapter in the changing landscape of education," 2023, Stable Diffisusion, https://stablediffusionweb.com. Licensed under a CC0 Universal Public Domain Dedication per Stable Diffusion Terms, https://web.archive.org/web/20230925151555/https://stablediffusionweb.com/ ↵

- This is not in fact a personification of ChatGPT, but a reference to the principle of machine learning that the AI operates on. ↵

- ChatGPT, "ChatGPT's 'auto-complete' response to the prompt 'an apple a day,'' 2023, OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com/ ↵

- This description of the platform was generated by ChatGPT itself and revised for clarity. ↵

- @dsmerdon. “Why Does ChatGPT Make up Fake Academic Papers? By Now, We Know That the Chatbot Notoriously Invents Fake Academic References. E.g. Its Answer to the Most Cited Economics Paper Is Completely Made-up (See Image). But Why? And How Does It Make Them? A THREAD (1/n) 🧵 Https://T.Co/KyWuc915ZJ.” Twitter, 27 Jan. 2023, 9:42 PM, https://twitter.com/dsmerdon/status/1618816703923912704. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- Lutkevich, Ben. “Definition: AI Hallucination” TechTarget, https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/AI-hallucination. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- OpenAI further elaborate on the challenges of fixing this issue: “(1) during RL training, there’s currently no source of truth; (2) training the model to be more cautious causes it to decline questions that it can answer correctly; and (3) supervised training misleads the model because the ideal answer depends on what the model knows, rather than what the human demonstrator knows.” Introducing ChatGPT. OpenAI, 30 Nov. 2022, https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- ChatGPT, "An example of an individual using ChatGPT to “mine the collective” in order to find the “right words” for a thank you note," 2023, OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com/ ↵

- Awati, Rahul. “Definition: Garbage in, Garbage out (GIGO)." TechTarget, https://www.techtarget.com/searchsoftwarequality/definition/garbage-in-garbage-out. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- Perrigo, Billy. "OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour." Time, 18 Jan. 2023, https://time.com/6247678/openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- Murray, Donald M. The Essential Don Murray: Lessons from America’s Greatest Writing Teacher. Boynton/Cook Publishers/Heinemann, 2009. ↵

- Gegg-Harrison, Whitney. “Against the Use of GPTZero and Other LLM-Detection Tools on Student Writing.” Medium, 26 Apr. 2023, https://writerethink.medium.com/against-the-use-of-gptzero-and-other-llm-detection-tools-on-student-writing-b876b9d1b587. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023 ↵

- Gegg-Harrison, Whitney. “Against the Use of GPTZero and Other LLM-Detection Tools on Student Writing.” Medium, 26 Apr. 2023, https://writerethink.medium.com/against-the-use-of-gptzero-and-other-llm-detection-tools-on-student-writing-b876b9d1b587. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023 ↵

- Klee, Miles. "Texas A&M Professor Wrongly Accuses Class of Cheating With ChatGPT." Rolling Stone, 17 May 2023. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/texas-am-chatgpt-ai-professor-flunks-students-false-claims-1234736601/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- Harding, Xavier. “Chat GPT Detector? How To Tell If Text Was Made By AI.” Mozilla Foundation, 14 Apr. 2023, https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/blog/how-to-tell-chat-gpt-generated-text/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- Bauschard, Stefan. “How I Defeated an AI Plagiarism Detector with 2 Words.” Education Disrupted: Teaching and Learning in An AI World, 2 July 2023, https://stefanbauschard.substack.com/p/how-i-defeated-an-ai-plagiarism-detector. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- Cohen, Elizabeth G., et al. “Can Groups Learn?” Teachers College Record, vol. 104, no. 6, Sept. 2002, pp. 1045–68. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810210400603. Accessed 21 Sept. 2023. ↵

- ChatGPT, "An example of a user collaborating with ChatGPT to think more deeply about 'willpower,'" in response to the prompt, "I would define willpower in connection to words like perseverence and determination. To me personally, it's a form of self-discipline toward a specific purpose," 2023, OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com/ ↵

- Liu, Danny and Adam Bridgeman. "ChatGPT Is Old News: How Do We Assess in the Age of AI Writing Co-Pilots?." Teaching@Sydney, 8 June 2023, https://educational-innovation.sydney.edu.au/teaching@sydney/chatgpt-is-old-news-how-do-we-assess-in-the-age-of-ai-writing-co-pilots/. ↵

- Maeda, John. “Humanist Technologist.” John Maeda's Blog, 11 Feb. 2019, https://maeda.pm/2018/02/10/humanist-technologist/. Accessed 21. Sept. 2023. ↵