9.4–Diving into Research: Finding and Using Specific Sources

Dorothy Todd and Sarah LeMire

Once you have developed a topic, a good next step is to explore library databases to see what research you can find on that topic. When writing about literature, there are a number of types of sources that you can use as support for your writing, depending on your particular topic.

- The most common type of source is literary criticism, or books and articles that analyze literature. For instance, this type of source might look like an article analyzing the importance of clothing in Twelfth Night.

- It is also common to include sources from other disciplines, such as psychology or history. For instance, a history book about clothing in the Elizabethan era might be useful for a paper about gender and clothing.

The campus library is a good place to start looking for sources. Unlike search engines or publicly available databases like Google Scholar, library databases often focus on specific disciplines, so you are more likely to get relevant results.

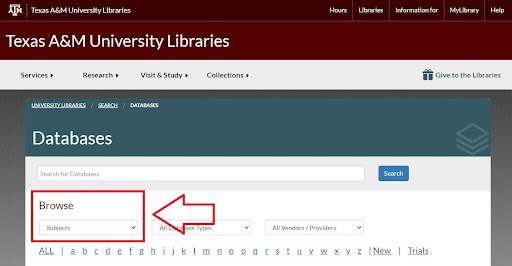

To get started, go to the library homepage at library.tamu.edu and click on the Databases tab.

You can browse by subject, as pictured in Figure 8.4, to see the databases for different disciplines. If you’re writing about a work of literature, often the English databases are the best place to start. If you’re writing about a film, you may want to check out the film databases. Don’t forget that databases for other disciplines may be helpful as well.

A common database to use for literary research is MLA International Bibliography, which is found listed with the English databases. MLA International Bibliography and other literary criticism databases contain a variety of sources, including references to print sources like books and book chapters.

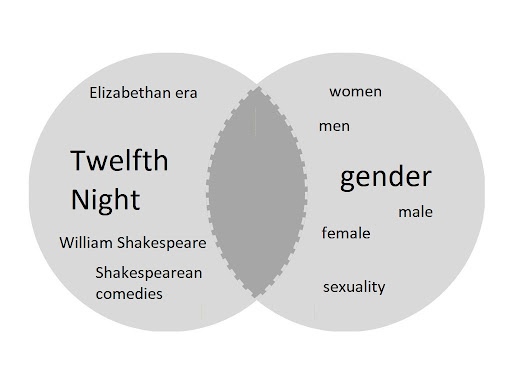

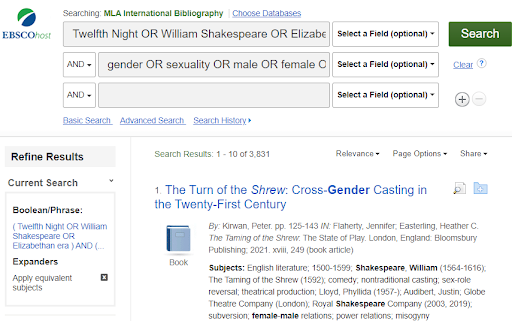

The search in MLA International Bibliography and many other databases operates like the Venn diagram previously described. Because discipline-specific databases are more focused than interdisciplinary databases like Google Scholar, it often helps to brainstorm several alternate terms for your intended topic before entering your search in the database. For instance, if you’re interested in issues of gender, searching for terms like sexuality, men, women, male, and female can be useful alternate terms to finding sources related to gender (Figure 8.5). Similarly, you could search for the author of your text, its time period, or its genre in addition to searching for the title of the text. This strategy is particularly helpful when searching for contemporary texts or texts that have not been written about as extensively as Shakespearean texts.

Once you have brainstormed your search terms, you can enter them in the database (Figure 8.6). All of the terms from the first circle of your Venn diagram will go in the same search box, while all of the terms from the second circle of your Venn diagram will go in the second search box. As your topic begins to come into focus, you may add a third or fourth circle (or more) to your Venn diagram.

You can connect search terms in a library database using Boolean operators. Boolean operators are the terms AND, OR, and NOT. These terms tell the database how to interpret your combination of search terms:

- AND tells the database to look for items that include all of your search terms (e.g., results that talk about both gender and Twelfth Night).

- OR tells the database to look for items that include either of your search terms (e.g., results that talk about either Twelfth Night or Shakespeare).

- NOT tells the database to exclude a term. For instance, you might want items that talk about Twelfth Night and gender, but that exclude sources about dress. Use this operator with caution, though, as it is easy to inadvertently exclude relevant sources.

Your search results will give you a sense of how much your topic has been written about in scholarly literature. For this search, there are thousands of sources available, and you will want to narrow down your results. For other topics and texts, there may be very few or even no sources available. That’s okay! Thinking conceptually about your topic can help you find sources to support your argument. Think again about other ways to search for your topic. In which genre or genres does your text belong? If you are writing about the importance of music in Night of the Living Dead, you might search for Night of the Living Dead OR horror movies. If you are writing about revenge in Cask of Amontillado, you might search for Cask of Amontillado OR mysteries.

Once you have refined your search strategy, you can begin to look through the sources you’ve retrieved. Some sources, like many journal articles, will be available electronically. Other sources, like the one in Figure 8.6, are found in books on the shelf. To view these sources, you can retrieve the book from the shelf, or you can make a request to have the book retrieved for you. Although electronic sources can be easier to access, don’t discount the value of print sources. You may find all of the sources you need with just a quick trip to the stacks.

Reading Literary Criticism and Other Secondary Sources

Once you’ve found sources that look promising, it’s time to dig into them. When reading literary criticism and other secondary sources, you want to practice the same active reading strategies you employ when reading any text for your college courses. These strategies include, but are not limited to, highlighting, underlining, taking notes, and asking questions of the text. Staying actively engaged with texts while reading them leads to better comprehension and helps you develop a sense of how other writers build arguments and convey information.

Along with the active reading strategies you are used to employing, here are a few specific strategies that will help you navigate the nuance and complexity of literary criticism and other secondary sources:

- Ask yourself why you are reading the source. What about the source initially made it look promising when you were sorting through sources? What do you hope to learn or discover from this source?

- Identify the source’s thesis or main argument. Literary criticism and other forms of secondary sources often employ a standard structure, so look for an articulation of the source’s main argument at the end of the introductory section of the source.

- Identify the larger context or conversation in which the author is making their argument. Are they responding directly to other scholars? Do they reference other lines of thinking that precede them? Do they explicitly or implicitly position themselves within a particular school of thought or employ a particular theoretical lens?

- Trace the relationship between the source’s higher-level arguments and lower-level arguments. How does the author’s evidence and analysis contribute to the source’s main argument or thesis? Creating a simple outline allows you to see these relationships more clearly and helps you identify successful strategies for organizing your own writing.

- Don’t worry if you don’t understand everything the first time you read the article. Literary criticism is dense, and you might have to reread sections of the source to comprehend it. You might need to look up words in a dictionary or do a quick Google search to familiarize yourself with new concepts.

- If you’ve employed active reading strategies and are still grappling with the source’s argument or evidence after reading the source a few times, don’t be afraid to reach out to your instructor. Your instructor can be a great resource in helping you distill a particularly complex source.

Joining the Conversation is Not Repeating the Conversation

Once you get a sense of the conversations that are occurring, it is time to think about how you might join one or more of them. Keep in mind that repeating the conversation is not the same as joining the conversation. You don’t want merely to describe the conversation that is taking place. Instead, you want to engage actively in it, and that means building upon, responding to, disagreeing with, or refining the ideas that currently make up the conversation. Simply repeating the conversation rather than contributing to it is a common pitfall among college writers, and students tend to find themselves in this position when they try to apply the following type of logic in their arguments:

- I argue that metonymy figures prominently in this poem.

- Scholar X also argues that metonymy figures prominently in this poem.

- I am correct in my argument that metonymy figures prominently in the poem because someone before me made the same argument.

Keep in mind that you want to contribute to the conversation about a text rather than only use the conversation to support your own ideas about the text. You also want to avoid only cherry-picking pieces of the conversation that support your own argument. Instead, you want to make space for your argument within the conversation by engaging critically with the ideas circulating within the conversation. Disagreeing with an idea is a straightforward way of entering into the conversation, but to contribute meaningfully to the conversation, you need to disagree with an idea AND explain why you disagree. Similarly, simply agreeing with an idea might help you enter the conversation, but in order to make yourself an important part of the conversation, you need to agree with an idea AND refine, expand, nuance, or otherwise build upon the idea with which you agree. This distinction may seem small, but approaching a literary essay as a conversation to which you are contributing will radically change how you conceptualize your argument, how you engage with scholars, and how you utilize evidence.

Attribution:

Todd, Dorothy, and Sarah LeMire. “Writing a Literary Essay: Moving from Surface to Subtext: Diving into Research: Finding and Using Specific Sources.” In Surface and Subtext: Literature, Research, Writing. 3rd ed. Edited by Claire Carly-Miles, Sarah LeMire, Kathy Christie Anders, Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, R. Paul Cooper, and Matt McKinney. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2024. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Books, essays, and articles that analyze literature. Usually falls under the category of secondary sources.

The terms AND, OR, and NOT, all of which tell the database how to interpret your combination of search terms.

Uses a closely related idea or object to stand-in for something.