9.2–Joining the Conversation

Dorothy Todd; Claire Carly-Miles; Sarah LeMire; and Kathy Christie Anders

The best way to get off on the right foot as you begin the writing process is to think of your writing as part of a conversation. Now you might be asking yourself, “How is writing a conversation?” After all, when we think of writing, we tend to think of the solitary individual putting pen to paper or maybe even the flutter of anxiety that emerges when it’s just you, a blinking cursor, a blank computer screen, and a looming deadline. Yet if we stop and think about it, writing is almost always a response to the circulation of ideas happening around us. A student might write an op-ed in the university newspaper in response to a new campus policy. A child at summer camp might write a letter to their best friend at home after making friendship bracelets during arts and crafts. You have probably written many assignments in which you participate in a conversation by responding to a question that your instructor posed. In all of these instances, writing occurs in response to, and in conversation with, other ideas. But even if an instructor does not provide a specific prompt to which you should respond, a good writer will still enter into conversations through their writing. Consider this oft-cited passage by philosopher Kenneth Burke and how this understanding of conversations might inform the way we write:

You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. . . . You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him. . . . The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in process.

—Kenneth Burke, The Philosophy of Literary Form[1]

From the standpoint of writing a literary essay with research, the most striking element of this passage is the idea that we do not jump headlong into the conversation without first getting a sense of the conversation. Just as it would be foolhardy to launch a boat into a stream without first determining the depth and speed of the water, as well as what lies downstream, it is injudicious to enter a conversation until you know the nature of it. When we do decide to enter the conversation by stating our argument—what Burke refers to as “put[ting] in your oar”—we do so using the language, rhetorical strategies, and agreed-upon conventions of the conversation. You will not be rhetorically effective if your argument does not reflect and respond to the conversation into which you are entering.

Finding Your Voice

Joining the conversation, however, does not mean losing your individual voice. In fact, joining the conversation allows you to find and amplify your voice as you bring your unique perspective into a conversation that has previously not benefited from your presence. Students sometimes think that the mark of “good” academic writing is inscrutability. The longer the sentences and the more obscure the words, the better the argument, or so the thinking goes. Remember, though, that the goal of all writing is to communicate one’s ideas and arguments clearly and effectively. The best writing thus occurs when a writer effectively navigates complex, multifaceted ideas through the clarity and precision of their own unique voice.

A Note About Academic Conventions

While bringing your unique voice to the conversation is invaluable, you should also remember that there are certain agreed-upon conventions when it comes to writing about literature. For instance, we use present tense when we write about literary works because the actions with the texts are considered to be always happening. When you think about it, it makes sense: you can open a book to the same section at different times in your life and there are the same words conveying the same actions (although not always the same meaning). For example, if you are composing an essay about Twelfth Night,[2] you might write the following:

In the play’s open scene, Orsino remembers, “O, when mine eyes did see Olivia first, / Methought she purged the air of pestilence” (1.1.20-21).

Even though Orsino uses past tense to tell us what he is recalling from his past, you, the literary critic, use present tense when you are writing about it.

Finding Out What’s Out There: Discovery and Exploration

Now that we have established how the process of writing about literature begins by joining a conversation, you might be wondering how you find these conversations! Your instructor will probably point you toward some of them, perhaps by introducing a particular theoretical framework for studying a text or by assigning a secondary source for you to read in conjunction with a primary text. However, to really find out what kinds of conversations scholars are having about a particular text—and to identify how you might contribute to that conversation—you will need to do exploratory research.

Before moving into any exploratory research you might undertake, however, let’s define a few important terms you will undoubtedly encounter. Primary texts, or primary sources, are typically original sources upon which scholars base other research. Primary sources have not been filtered through analysis or evaluation and are fixed in the time period involved. Letters, diaries, manuscripts, and even social media posts are common types of primary sources. In ENGL 203, you will commonly encounter other primary sources: novels, plays, poetry, stories, etc. Secondary texts or sources are often created using primary sources. They typically involve analysis or evaluation of primary sources, often with the benefit of hindsight or distance from the time period involved. Commentaries, criticisms, and histories are a few common types of secondary texts.

There are many types of research that happen with literary texts. In the case of older works, you may discover that there are conversations about the text that have been going on for hundreds of years, and you may be more interested in what contemporary scholars have to say about a work than what scholars from one hundred years ago have posited. You might be interested in the history of how a text was physically created and published, or you might want to know about how a text fits into the historical circumstances in which it was composed. Whenever you begin trying to get a sense of what is being said about a text, you may begin exploring secondary texts.

Sometimes this might begin as a Google search, or by perusing a Wikipedia entry. This type of browsing and exploration can help you discover in broad strokes the conversations surrounding a text. As you do this, note which words people use to describe those questions. For example, if you are looking for topics regarding a certain literary theory, you may find that scholars in that area use specific terms for that theory, such as “feminist” or “psychoanalytic.” If you do any preliminary searching in engines like Google, examine your results for key terms that stick out, and make a note of them so you can use them to browse in library databases. While sources like Wikipedia can be helpful for discovering terms, browsing in a library database will let you refine a topic by showing you material that is specific to literary scholarship, much of which is not available openly on the web.

Exploring databases or journals can be a great way to uncover the conversation about a particular work of literature. Maybe you have to write a paper incorporating a theoretical lens about one of the texts you’re reading this semester. You can try some exploratory searches in a database such as MLA International Bibliography to get an idea of what conversations about that text are already happening.

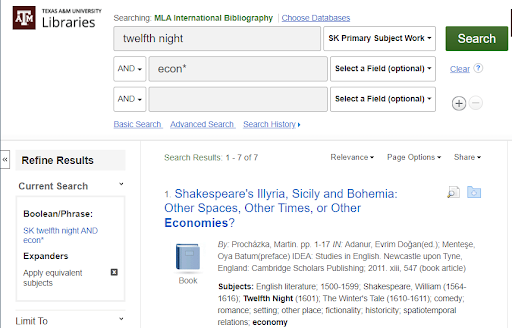

For instance, if you’re interested in writing an essay on Twelfth Night, you could try searching for Twelfth Night in MLA International Bibliography, as is depicted in Figure 8.1. By indicating that Twelfth Night is the Primary Subject Work, you’re telling the database that the articles it finds should be analyzing Twelfth Night. Once you’ve found items about Twelfth Night, you can start adding some additional terms in the second search box to indicate the theoretical lens you want to explore. You could try econ* to find materials discussing both Twelfth Night and economics/economies, or you might use the root term fem* to search for articles examining Twelfth Night within a feminist framework or to find articles that consider the play’s female characters. Tip: The * (asterisk) tells the database to look for terms with any ending after the text you added (e.g., fem* yields materials including any of the following words: female, feminine, feminism, feminist).

Exploratory searching can help you see how robust the conversation is about a particular topic. Searching for Twelfth Night AND econ* brings back only a handful of results, while Twelfth Night AND fem* brings back many results. (See “Diving into Research” for more detailed information about strategies about successful database searching.) This tells you that there is much more conversation happening about Twelfth Night using a feminist lens (although that doesn’t mean that an economic reading of Twelfth Night isn’t a valid one).

Exploratory searching doesn’t just help you see whether there are a lot of sources available on a particular text or topic. Such searches will also help you start to understand the conversation that is happening. Recall the analogy by Burke at the beginning of this chapter: in order to put your own oar (your claim or argument) into the stream (the critical conversation, or what credible sources are saying about the topic), you must first assess that stream (read the sources), and then dip your own oar in (write your own response).

Clicking on “Find Text @ TAMU” will bring you to the article/book chapter/book, if available electronically. Take a look at some of the abstracts to help you get a sense of the ways that other scholars are applying that theoretical lens to the text you’re interested in. Does anything pique your interest? Does it give you any ideas on how you could apply that theoretical lens in your own way in order to contribute to the conversation?

One important thing to note about this type of exploratory searching is that not every text is written about as extensively as Twelfth Night. If you try searching for the title of your text and don’t get any or very few, results, here are a few strategies you can try:

- Simplify your search. Search for the title of your text alone, without any filters like “Primary Subject Work” or theoretical lenses.

- Add alternate terms, like the author’s name. For example, you could search Twelfth Night OR William Shakespeare.

- Add broader terms like the genre or time period. For example, Twelfth Night OR William Shakespeare OR drama OR Elizabethan.

Attribution:

Todd, Dorothy, Claire Carly-Miles, Sarah LeMire, and Kathy Anders. “Writing a Literary Essay: Moving from Surface to Subtext: Joining the Conversation.” In Surface and Subtext: Literature, Research, Writing. 3rd ed. Edited by Claire Carly-Miles, Sarah LeMire, Kathy Christie Anders, Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, R. Paul Cooper, and Matt McKinney. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2024. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Kenneth Burke, The Philosophy of Literary Form, 3rd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 110–11. ↵

- William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, eds. Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine (Washington, DC: Folger Shakespeare Library, n.d.), https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/twelfth-night/. ↵

Writer’s unique style that emerges from combination of word choice, sentence structure, tone, and point of view.

A group of related ideas or theories that can be used to examine a text in a particular way.

Typically original sources upon which scholars base other research. Primary sources have not been filtered through analysis or evaluation and are fixed in the time period involved. Letters, diaries, manuscripts, and even social media posts are common types of primary sources.

Texts often created using primary sources. They typically involve analysis or evaluation of primary sources, typically with the benefit of hindsight or distance from the time period involved. Commentaries, criticisms, and histories are a few common types of secondary texts.