1.2–Words, Words, Words

Claire Carly-Miles; Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt; R. Paul Cooper; and James Francis, Jr.

At its surface, literature is words, but is any word-focused text literature? Well, no. While avant-garde, experimental art might render newspapers, lab reports, or phone notifications into literature, we generally agree that such forms of writing are not literary. While experimental art shows how loose the category “literature” can be, literariness is most often judged according to traditional, established communities with shared values, tastes, and expectations regarding form, conventions, subjects, and themes. While what counts as literary might not always be clear, it is clear that what separates the literary arts from other kinds of arts, such as performing and visual arts, is the conveyance of meaning through words. In a literary text, the author delivers information to readers or listeners by way of human language as opposed to instrumental music or various performance arts.

Authors use words to do any or all of the following things (to list just a few). Words may

- appeal to some or all of our five senses (visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory, tactile) in order to create a physical experience of the work,

- create tone, from somber to humorous to anything in between,

- be arranged in ways so that the structure or placement of the words contributes to the meaning(s) of the work as a whole,

- describe characters through their looks, their actions, and the consequences of their actions,

- construct images or symbols in order to convey meaning(s),

- entertain, delight, and distract.

What are some of the other purposes for words that you can think of? If you take some time to reflect, you may come up with a wide variety of uses, ranging from worshiping a deity, teaching a lesson, or comforting someone in distress to insulting someone (even if only in your head), making puns, or chatting about the weather. Words can be powerful, banal, useful, decorative, helpful, or hurtful, and sometimes all at once. Because they are such a powerful and versatile medium, they are particularly useful when creating meaning and delivering information.

In thinking about the distinction between narratives that use words as opposed to narratives that use visual language, it may help to compare multiple adaptations of the same story. Shakespeare’s Othello (1602–1603) tells the tragic story of the titular Othello, a Moorish general who is convinced by his trusted subordinate Iago that his wife Desdemona is cheating on him with his second-in-command, Cassio. Toward the end of the third act of this five-act play, Iago puts into action his plan to convince Othello of Desdemona’s alleged infidelity. In this scene (excerpted below), Iago makes Othello believe that because he is happy, he must therefore not be aware of the terrible things that are (supposedly) happening right under his nose.

Othello Excerpt[1]

IAGO

O, beware, my lord, of jealousy!

It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock

The meat it feeds on. That cuckold lives in bliss

Who, certain of his fate, loves not his wronger;

But O, what damnèd minutes tells he o’er

Who dotes, yet doubts; suspects, yet strongly loves!

OTHELLO

O misery!

IAGO

Poor and content is rich, and rich enough;

But riches fineless is as poor as winter

To him that ever fears he shall be poor.

Good God, the souls of all my tribe defend

From jealousy!

OTHELLO

Why, why is this?

Think’st thou I’d make a life of jealousy,

To follow still the changes of the moon

With fresh suspicions? No. To be once in doubt

Is once to be resolved. Exchange me for a goat

When I shall turn the business of my soul

To such exsufflicate and blown surmises,

Matching thy inference. ’Tis not to make me jealous

To say my wife is fair, feeds well, loves company,

Is free of speech, sings, plays, and dances well.

Where virtue is, these are more virtuous.

Nor from mine own weak merits will I draw

The smallest fear or doubt of her revolt,

For she had eyes, and chose me. No, Iago,

I’ll see before I doubt; when I doubt, prove;

And on the proof, there is no more but this:

Away at once with love or jealousy.

IAGO

I am glad of this, for now I shall have reason

To show the love and duty that I bear you

With franker spirit. Therefore, as I am bound,

Receive it from me. I speak not yet of proof.

Look to your wife; observe her well with Cassio;

Wear your eyes thus, not jealous nor secure.

I would not have your free and noble nature,

Out of self-bounty, be abused. Look to ’t.

In the excerpt above, we encounter all of the narrative through words. (In the context of an actual stage performance, meaning could also be supplemented through gestures and other dramatic elements such as music, props, or costuming.) In his initial bid to convince Othello, Iago relies on rhetorical techniques as opposed to visual evidence. First, Iago appeals to Othello’s noble nature and pride, begging him not to be swayed by strong emotions such as “the green-eyed monster” (3.3.196) jealousy. Othello, in response, insists that his nature is steadfast and he will not be easily swayed by emotions or doubts as opposed to concrete evidence. Iago, “glad of this” (3.3.221), then emphasizes his role as Othello’s trusted friend and subordinate, implying that he does not want to see Othello hurt by Desdemona’s and Cassio’s actions.

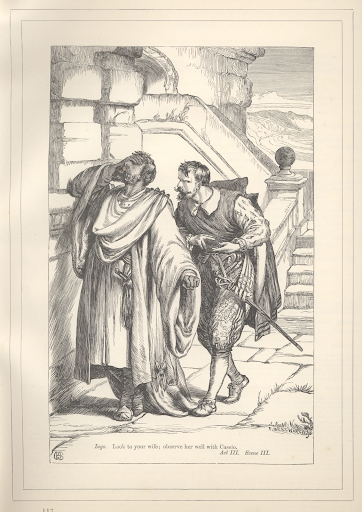

This word-centric approach stands in contrast to other artistic renderings of this same scene. In the image below from a Victorian edition of Shakespeare’s works (Figure 1.1[2]), illustrator H.C. Selous offers his interpretation of the scene. This illustration was transformed into a wood engraving by Frederick Wentworth so that it could be easily replicated in multiple copies, hence the lack of color and the abundance of lines representing color and shadow.

The above image conveys meaning that is not immediately available in the written text. Though someone has included Iago’s line, “Look to your wife; observe her well with Cassio,” the interaction between the figures representing Othello and Cassio conveys a very different meaning than the written script offers. In this engraving, Othello holds his right hand over his eyes and forehead while a sinister-looking Iago, with a furrowed brow and diabolical mustache, hunches behind him. If this were the Iago that Othello regularly encountered, we might reasonably wonder why Othello would ever trust him. The image shows Iago in a more sinister light by giving him features and body movements that evoke fictional villains; the visual depiction represents an exaggeration of the skillful wordplay from the original text to convey Iago as distrustful without using words. Othello, too, merits comment. Famously, Othello is a Black man (though his specific African heritage has been up for debate); in this image, Othello’s skin is darker than the white Iago’s, but his visible features are more Anglo than African. His appearance also is similar to certain depictions of Jesus Christ, suggesting that Othello’s suffering may be akin to Christ’s, especially when placed against the more devilish-looking Iago. Othello’s hand over his eyes may also be read as a common depiction of distress or his concern over being cuckolded. In medieval and early modern times, the symbol of a cuckold (or a person whose spouse was cheating on them) were horns sprouting from the wronged party’s head. Othello himself makes a reference to this later in the same scene when he complains of a headache.

Hybrid Forms: Word + Image + Sound + Movement

Other forms that combine words with other media are also considered “literature,” though in order to really understand them, you will need to employ multiple ways of reading. These combined forms are often called hybrid forms as they combine a written or spoken word with at least one other major medium. Popular combinations that you are likely familiar with include movies and television shows, both of which use scripts and actors delivering dialogue alongside important visual and aural elements such as camera angles, sound effects, costumes, sets, music, and film editing to tell a story, convey a mood, teach a lesson, or entertain. Plays and other performances including musicals and operas also use both words and other forms (music and movement being the most noticeable) and operate similarly in requiring their viewer to be attuned not only to literary conventions but also to dramatic, filmic, and musical conventions to be able to comprehend several layers of meaning.

Let’s take a look at an extended example in film, which frequently features both spoken language and what’s known as film language. One of the common features of film language is distinct shots or camera angles. Take for example a conversation between two characters in a movie or television show. For a neutral conversation wherein the two characters are in equal power, the camera will keep the size of their heads (relative to the entire frame) the same. This visually signals to the viewer that the conversation is between relative equals. If a cinematographer or director wished to play with power distinctions or to privilege one person’s stance over the other, they could vary the shots to have one character appear higher in the frame over the other. In these instances, while the dialogue is still conveying its own meaning, the visual language of film also conveys substantial meaning.

Other hybrid forms, or forms that combine multiple mediums, include the large and popular categories of graphic novels, music with lyrics, and several kinds of avant-garde or experimental poetry. A graphic narrative combines words and pictures in order to convey its message, usually providing more page space to the images that are separated in a (usually) linear fashion. Popular graphic narrative genres include graphic novels (long-form fiction or non-fiction that uses both images and word), comics (shorter, illustrated stories that also use words for dialogue, sound effects, or establishment of a scene), manga (an extremely popular form of Japanese graphic narrative that is read from right to left), and adaptations of previously text-only works (see, for example, the recent releases of Ann M. Martin’s The Baby-Sitters Club series that present the original stories entirely in graphic novel form). Combining the visual and verbal so explicitly strikes a chord with several audiences. Unlike other, word-heavy forms like novels, these graphic forms are often faster to read since they can quickly convey information using visual language and the relationship between different panels, particulars that would take much longer to describe with words alone.

Creators often like to “push the envelope” and experiment with multiple forms. Whether as a form of protest against limited and proscriptive modes of expression, a form of conscious experiment on the limits of meaning or feeling, or even a form of play, these hybrids typically do not appear in conventional locations such as printed books or in literary journals, even by presses that report to be more radical. Indeed, many hybrid forms of the twenty-first century are thoroughly digital, using the logic of code as opposed to linear pages to organize a text and either direct or challenge a reader or viewer’s engagement. A fascinating example of a hybrid piece of literature is The Last Performance,[3] created and maintained by hybrid language artist Judd Morrissey. Described as “a constraint-based collaborative writing, archiving and text-visualization project responding to the theme of lastness in relation to architectural forms, acts of building, a final performance, and the interruption (that becomes the promise) of community,” this project combines several forms, including written and visual submissions from individual contributors, inspiration and active responding to performance group’s Goat Island, and architecture in the design of a virtual dome.[4] Viewing the project from a browser challenges the reader, forcing them to break from their usual linear reading habits and to think through language, performance, and space, both real and virtual.

Attribution:

Carly-Miles, Claire, Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, R. Paul Cooper, and James Francis, Jr. “Introduction: Words, Words, Words.” In Surface and Subtext: Literature, Research, Writing. 3rd ed. Edited by Claire Carly-Miles, Sarah LeMire, Kathy Christie Anders, Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, R. Paul Cooper, and Matt McKinney. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2024. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- William Shakespeare, Othello. Eds. Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine. (Washington, DC: Folger Shakespeare Library, n.d.), 3.3.195–228, https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/othello/act-3-scene-3/. ↵

- H.C. Selous and Frederick Wentworth, “Iago and Othello” in The Plays of William Shakespeare, eds. Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke (London, Paris and Melbourne: Cassell & Company, Limited, [1864–68?]), 117. Available at Michael John Goodman, Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive, https://shakespeareillustration.org/2016/08/10/iago-and-othello-2/. ↵

- Judd Morrissey, Goat Island, et al, The Last Performance, 2007–2009, http://thelastperformance.org/title.php. ↵

- Judd Morrissey, Goat Island, et al, “The Last Performance [dot org],” The Last Performance, 2007–2009, http://thelastperformance.org/project_info_public.php. ↵

In general, any movement in the arts that is formally and aesthetically experimental; avant-garde poetry, avant-garde music, etc.

The attitude of the text toward its subject and themes.

The placement of the words, narrative structure, etc.

A description using concrete language, often engaging multiple senses at once; see: concrete language.

A thing that represents more than its literal meaning.

as noun, a husband whose wife has committed or is committing adultery; as verb, the process of making someone a cuckold. Term derives from the practice of Cuckoo birds who lay their fertilized eggs in a different type of bird’s nest in order to deceive that bird into brooding, hatching, and raising the Cuckoo’s offspring; also, to wear the “cuckold’s horns” derives from the image of stags fighting, in which the dominant stag subdues its opponent, and the loser of the challenge forfeits its mate to the winner.

Forms that combine written or spoken word with at least one other major medium.

Combines words and images; see: graphic novel.

A mode of sequential art, like comics, which offers full length stories. The form is rooted in popular genres of storytelling, but has been adopted beyond the realm of superheroes.

An extremely popular form of Japanese graphic narrative that is read from right to left.

The rendering of an artwork in another medium.