Appendix: Using Sample Documents Effectively

James Francis, Jr.

Writing Strategies

While constructing documents during the writing process, we often examine sample materials that can help us consider how to make our own writing more effective. Whether we are writing a research report, developing an analytical essay, creating a visual handout, crafting application materials for a job, or starting the next great novel, reviewing sample materials within the same genre of writing can be helpful in making decisions regarding the form and content for your text.

Although sample materials help writers, we have to be cognizant of how to use them effectively without falling into traps of basing our own work on them. When this situation occurs, writers may find themselves creating documents that are not appropriate for the intended audience, not unique to their own personal voice and style, and accidentally plagiarized by usurping someone else’s work without credit (see Chapter 12: Avoiding Plagiarism and Citing Sources Properly for more information). In this section, we will review a few tips to ensure that sample materials remain helpful in developing your own documents effectively.

As always remember to contact your instructor for any clarification on how they may want you to utilize sample materials. If you have questions or concerns before and/or during the construction of your writing—in form and/or content–reach out to them!

Formatting

Sample materials help demonstrate proper formatting techniques, particularly by showcasing standard elements. These elements include the following:

- Style manual guidelines

- Font selection and size

- Spacing

- Text alignment

- Headers

- Page Numbers

- Titles

- Paragraphs

- Figures (Tables, Graphics, Illustrations, Images)

- Documentation and Formatting

- In-text citations

- Figure labels

- Proper Nouns (Names of people or places; Titles of works)

- Source listing—for instance:

- Works Cited (MLA)

- References (APA)

- Bibliography (Chicago)

- Harvard (Reference List)

- Organization

- Paragraph structure

- Chronology of content

- Linear (sequential)

- Reverse (conclusion to beginning)

- In medias res (starting in the middle)

- Visual Appeal

- Color

- Emphasis (Bold, Underline, Italics, Highlights)

- Font selection and size

- Text alignment

- Figures

- Spacing

- Framing

This is not an exhaustive list, and depending on the type of document you are creating, some or all of these elements might require consideration in making your document the most effective for its intended audience and the assignment guidelines. The ways in which a document appeals to the reader help make a rhetorical connection to its content. When you examine any of these elements in sample materials, evaluate how they impact the content and the message conveyed to the intended audience. As you develop your materials, focus on the purpose, objective, and goal of the document(s) so that you may format the work as most appropriate to the rhetorical situation.

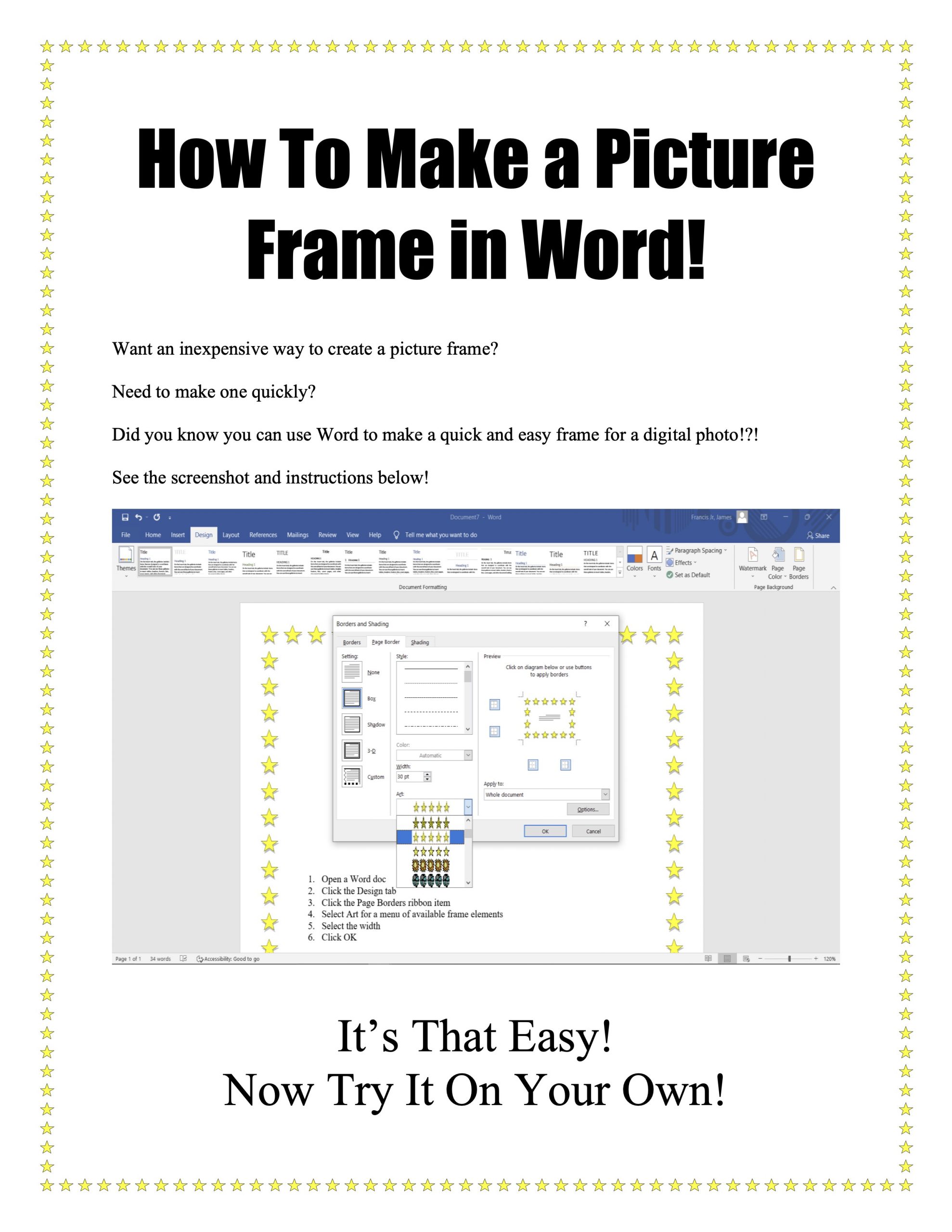

What you take away from reviewing the form of sample materials should be ideas to apply to your documents in unique ways that align with what you hope to accomplish—not a carbon copy of what someone has already produced for a sample, even if that sample represents one way to address the assignment guidelines. Let’s take a look at an example for making an informational handout (Figure 24.1[1]) and a similar document created using the exact same formatting (Figure 24.2[2]):

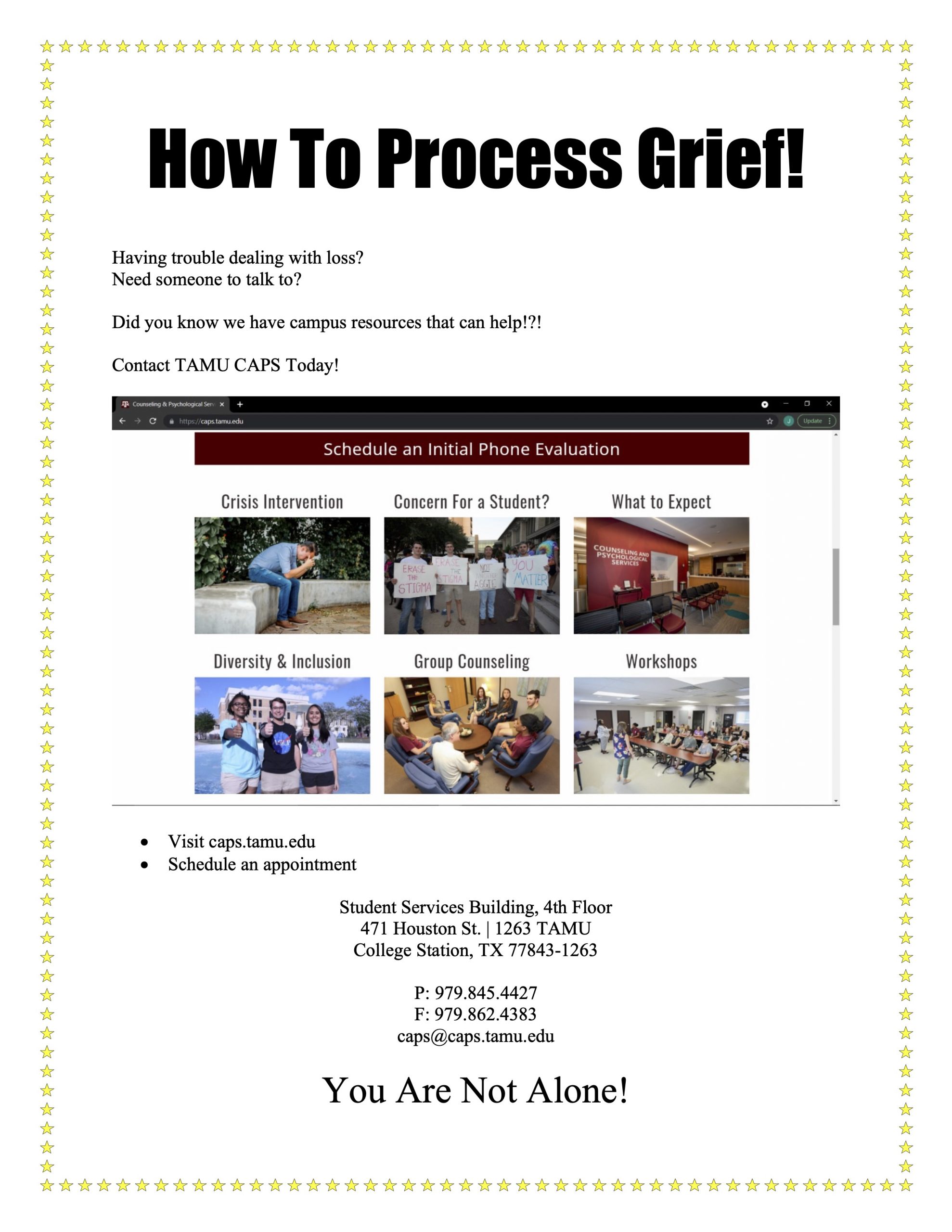

The student handout in Figure 24.2 assumes similar design elements of the sample without consideration of their specific subject matter. Because of this oversight, the handout is ineffective because the design elements are neither unique nor suitable for the subject matter; furthermore, the information and the tone of the content do not complement the subject matter. In order for the student to create a more effective handout, they should only use the sample to consider how it merged its form and content to relate to the topic and its intended audience. Evaluating the sample presents the student with the following question: How do I format my handout so that the design principles respond to the content and connect with the intended audience? Here is the revised student handout (Figure 24.3[3]):

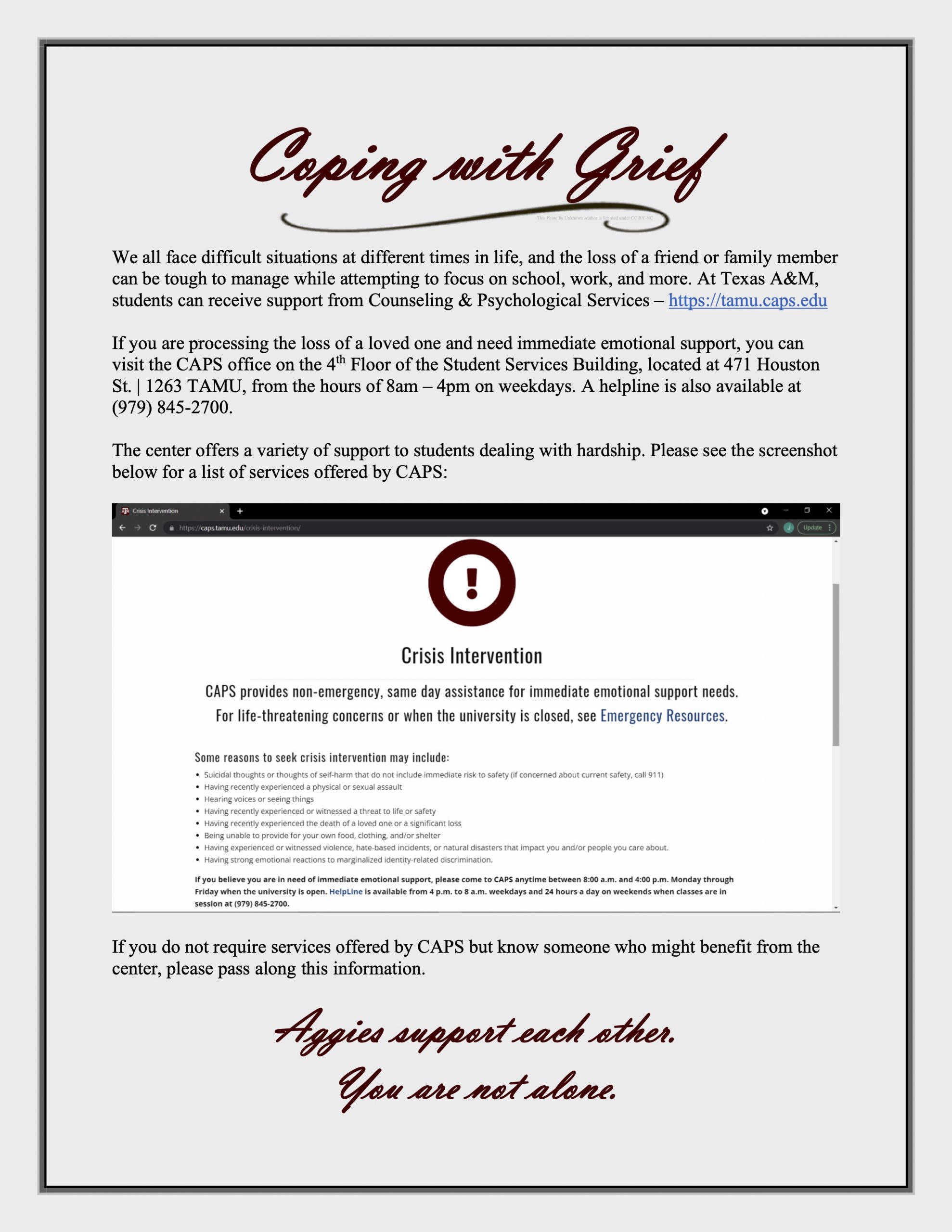

In the revised handout we can recognize principles of effective design (See Chapter 7: Design) that the sample handout demonstrates, as well as that the student’s work represents an original document that benefitted from reviewing sample materials. They have created a document that is now balanced in its form and content to deliver information to its audience in an appropriate tone. But as illustrated above, let’s not forget that formatting represents only half of what we need to examine to create effective materials.

Content

Organization of content is slightly different from the technical aspects of formatting, but it still follows the same understanding that a sample document can help you consider how to arrange your writing without following the exact structure of the sample. When organizing content within a document, the writer should ensure that the text flows (i.e., includes transitions from one point to the next) and achieves clarity of communication. If you follow a sample document’s organization and general setup too closely without concern for how your writing needs to be original, the content might not seem logical, fluid, or relevant to the assignment guidelines. Here is an example that demonstrates a report of findings from primary research (note: all sources and in-text citations have been created for sample use only):

Sample Report Text

Once the survey period concluded, we tallied the final numbers and discovered more people liked the design with the blue background as opposed to the orange background. The color selection follows what Hinojosa mentioned in her article about orange causing a soporific effect (a tendency toward sleepiness and often boredom). As a result—from the surveys and research experts—we propose that the new team uniforms use the selected design with a blue background for the next season.

Student Report Text

When our survey period ended, we counted the final numbers and discovered more people liked the garlic toppings instead of the cinnamon toppings. The more-savory food topping selection agrees with what Pham detailed in their source about people having an aversion to mixing toppings—like cinnamon—that cause effluvia. In conclusion, we recommend that the pizza restaurant make the cinnamon topping a specialty item instead of a main-menu offering for patrons.

By reproducing the same organization and delivery of the sample report text, the student’s work leaves out important, vital elements—documentation for the source, along with details and description to clarify the writing—and they inadvertently plagiarize content. Always remember that samples are not examples of perfect writing because that concept does not exist; you must ask yourself what is and is not effective about the sample writing in order to consider how to avoid missteps—like not crediting a source—and how to translate a helpful writing strategy—such as providing a definition for transparency—into your own materials. Here is the revised student report:

Student Report Text (revised)

We counted the final numbers at the close of the survey period and the results showed that patrons of the pizza restaurant favored the garlic toppings over the cinnamon toppings, 72 to 28 (Figure 2.3). Supporting this finding, Pham (2019) claims, “Foodies prefer foods that taste and smell good because both senses have to be satisfied in the eating process” (p. 62). Based on our research, we recommend Pop’s Pizzeria making the cinnamon topping a specialty item instead of a main-menu offering, which will allow the establishment to simultaneously reduce the amount of product purchased each season and therefore reduce spending.

The revised content provides much more detailed, specific content to present the research findings; the survey results and academic source are properly documented; and the content offers a reason behind the recommendation. The student reviewed the effectiveness of the sample’s organization and content, and then they constructed their own report writing relevant to their project. And if you find yourself working with analysis instead of reporting, we can find similar ways to avoid replicating sample material organization and content delivery. Here is an example that demonstrates film analysis; the sample covers the text the student has been tasked to analyze:

Sample Analysis Text

Dee Rees’ Pariah contains symbols for the audience to unlock. One of those symbols is coded in the attire of the characters. Alike rejects stereotypical engendered clothing articles like dresses and the color pink for young girls. Instead, she prefers a do-rag, a ball cap, and baggy, comfortable clothes. She does this to access and present a more recognized masculine aesthetic to attract a potential love interest. De Santos writes, “People often use clothing to create a conversation concerning gender that they cannot put into words for fear of being ostracized” (37).

Student Analysis Text

In Pariah, we are provided symbolism throughout the film. The main character’s preferred name serves as a reminder that she exists as the “other” in the story. Alike prefers “Lee” instead of the name she was assigned at birth. This is ironic because she is completely unlike any of her immediate family members. She uses “Lee” to help demonstrate her masculine identity to attract other girls. Nakai is quoted as saying, “Some LGBTQ youth, upon coming into adulthood, disclose that their assigned names do not complement their self-identities” (70).

The student’s text mimics the exact sentence arrangement, presentation of discussion elements, and tone of the sample. Following the sample’s arrangement so closely makes the content sound choppy; the sentences are properly formatted, but they don’t seem to connect to each other to create a fluid discussion. Mirroring the sample analysis too closely also robs the student’s work of having a unique voice to set up the analysis, and furthermore, the sample incorporates secondary source material without fully integrating the quote. In the end, the writing becomes ineffective in communicating its message to the reader. Here is the revised student analysis:

Student Analysis Text (revised)

In Pariah (2011), the main character’s preferred name serves as a symbol that she exists as the “other” against additional characters in the film. Unlike her mother, father, and sister, Alike prefers “Lee” (the pronunciation of the second syllable in her name) instead of the name she was assigned at birth. The spelling of her assigned name is ironic because she is completely unlike her family members, and she prefers “Lee” because it feels more suitable to her understanding of butch-lesbian identity to attract other girls. The importance of naming and its connection to identity is further explored in “Nomenclature and the Self” by Dakoda Nakai. The writer claims, “Some LGBTQ youth, upon coming into adulthood, disclose that their assigned names do not complement their self-identities” (Nakai 70). As a coming-of-age film, Pariah demonstrates the disparate nature of naming and identity through Lee/Alike.

The revised content reveals analysis that is more connected structurally, which allows the student’s voice to clearly communicate its message and develop a full conversation with the incorporated secondary source. The content of your document, whether it be a handout, report, essay, novel, or other, needs to be unique—written from your perspective to respond to what the assignment requires and what the rhetorical situation demands. Organize your writing according to what the assignment guidelines stipulate, how you feel the text would be best represented, and in a manner that it connects clearly with your intended audience. When the organization is effective, the content of the document can equally accomplish its goals of communicating to the audience in the appropriate rhetorical mode.

Creative Writing: A Brief Note

Creative writing is all about invention: world-building, characterization, unique dialogue, story pacing, traditional vs. innovative narrative structure, and personal style for the author. Although many new and working writers revere the work of recognized, published authors, the goal is to establish your own voice in the field. Inspiration can veer close to imitation if a writer finds themself copying techniques—story structure, wording, setting, etc.—that another author has already established as their own. Without making any effort to distinguish between the two styles, the writer creates unoriginal work that—depending on the wording—could place them in a situation involving plagiarism.

Similar to crafting an instructions handout, researched report, or a literary analysis, the development of a creative writing piece—poetry, prose, stage play, and even film—can be aided by reviewing sample materials, but the work should avoid resembling an impersonation of another’s intellectual property. Experiment with different writing strategies, techniques, and forms to discover what methods work best for what you want to accomplish with the writing. Focus on form and content with regard to your intended audience and get creative!

Note

Using sample materials effectively takes a lot more consideration than we often think about when viewing and reading them. Always keep in mind that these materials are meant to help get us started in creating our own documents, to help us develop ideas unique to the assignment, and to act as a bridge to connect how form and content rely upon each other to resonate with the intended audience.

Seek the guidance of your instructor for any clarification needs about how to use the sample materials in your course. You might also utilize helpful services like the University Writing Center to develop your documents from their inception to their completion with the aid of a writing tutor and/or access the Writing & Speaking Guides to review handouts, podcasts, and videos to self-assist the specific needs of your document-creation.

- James Francis, Jr., “How to Make a Picture Frame in Word,” 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

- James Francis, Jr., “How to Process Grief!,” 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

- James Francis, Jr., “Coping with Grief,” 2021. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵